Since psychology as an academic discipline was developed mainly in North America and Western Europe, some psychologists began to worry about the fact that the designs that they adopted as universal were not as flexible and multivariant as previously thought, and did not work within others. countries, cultures and civilizations. Since there are questions as to whether theories related to the main issues of psychology (affect theory, cognition theory, self-concept, psychopathology, anxiety and depression, etc.), manifest themselves differently in other cultural contexts. Cross-cultural psychology revises them using methodologies designed to take into account cultural differences in order to make psychological research more objective and universal.

Differences from Cultural Psychology

Cross-cultural psychology is different from cultural psychology, which claims that human behavior is strongly influenced by cultural differences, which means that psychological phenomena can only be compared in the context of different cultures and to a very limited extent. Cross-cultural psychology, on the contrary, is aimed at searching for possible universal trends in behavior and mental processes. It is considered, rather, as a type of research methodology, rather than a completely separate area of psychology.

Differences from International Psychology

In addition, cross-cultural psychology can be distinguished from international psychology, which focuses on the global expansion of psychology as a science, especially in recent decades. Nevertheless, intercultural psychology, cultural and international, is united by a common interest in expanding this science to the level of a universal discipline capable of understanding psychological phenomena both in individual cultures and in the global context.

The first intercultural studies

The first cross-cultural studies were conducted by anthropologists of the 19th century. These include scholars such as Edward Burnett Taylor and Lewis G. Morgan. One of the most striking cross-cultural studies in historical psychology is the study of Eduard Taylor, which touched on the central statistical problem of intercultural studies - Galton. In recent decades, historians, and especially historians of science, have begun to study the mechanism and networks through which knowledge, ideas, skills, tools, and books have moved across different cultures, generating new and fresh concepts regarding the order of things in nature. Similar research adorned the golden fund of examples of cross-cultural research.

Studying intercultural exchanges in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 1560-1660s, Avner Ben-Zaken came to the conclusion that such exchanges occur in a cultural foggy locus, where the edges of one culture intersect with another, creating a “mutually encompassed zone” in which exchanges take place in peaceful way. From such a stimulating zone, ideas, aesthetic canons, tools and practical methods move to cultural centers, forcing them to update and refresh their cultural ideas.

Cross-Cultural Perception Studies

Some of the early fieldwork in anthropology and intercultural psychology focused on perception. Many people who are passionate about this topic are very interested in who first conducted the cross-cultural ethnopsychological research. Well, let's turn to history.

It all started with the famous British expedition to the islands of the Strait of Torres (near New Guinea) in 1895. William Hols Rivers, a British ethnologist and anthropologist, decided to test the hypothesis that representatives of different cultures differ in their vision and perception. The scientist’s guesses were confirmed. His work was far from final (although the subsequent work suggests that such differences are insignificant at best), but the scientist became the one who laid the interest in intercultural differences in academic science.

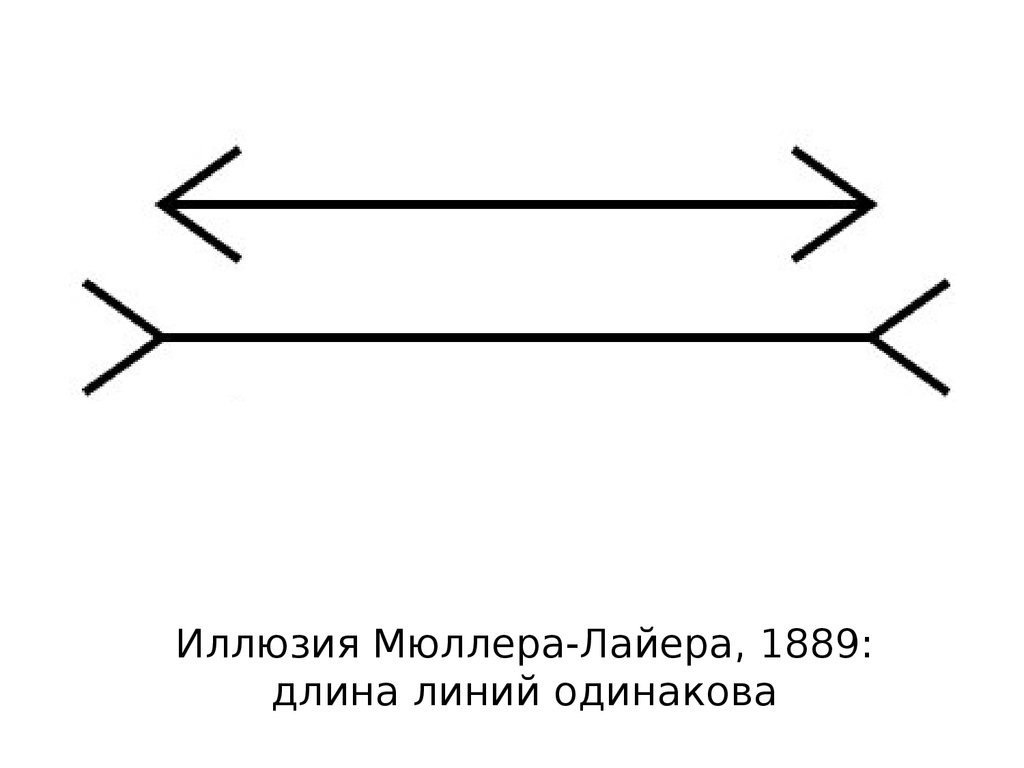

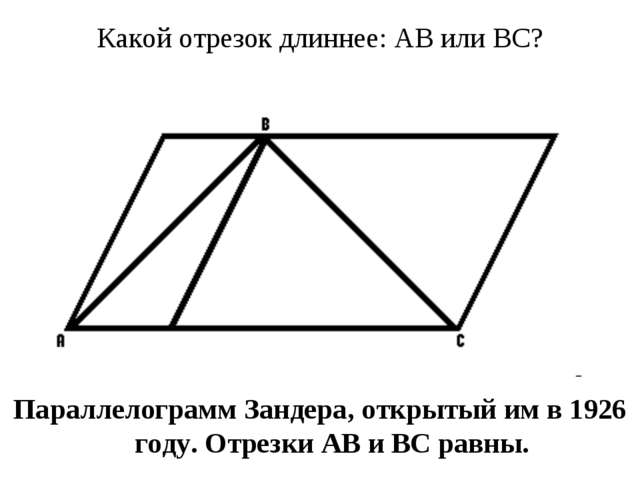

Later, in studies that are directly related to relativism, various sociologists argued that representatives of cultures with different, rather variegated dictionaries will perceive colors differently. This phenomenon is called "linguistic relativism." As an example, we consider a thorough series of experiments by Segall, Campbell, and Herskowitz (1966). They studied objects from three European and fourteen non-European cultures, tested three hypotheses about the impact of the environment on the perception of various visual phenomena. One hypothesis was that life in a "tight world" - a common environment for Western societies, in which rectangular shapes, straight lines, square angles predominate - affects the susceptibility to the Mueller-Layer illusion and the Zander parallelogram illusion.

As a result of these studies, it was suggested that people living in a very “built-up” environment quickly learn to interpret oblique and sharp angles as offset right angles, as well as perceive two-dimensional patterns in terms of their depth. This would make them see two figures in the illusion of Mueller-Lier as a three-dimensional object. If the figure on the left was considered, say, the edge of the box, that would be the leading edge, and the figure on the right would be the trailing edge. This would mean that the figure on the left was larger than we see it. Similar problems arise with the illustration of the Sander parallelogram.

What would be the results for people living in barrier-free environments where rectangles and right angles are less common? For example, the Zulus live in round huts and plow their fields in circles. And they were supposed to be less susceptible to these illusions, but more susceptible to some others.

Perceptual relativism

Many scholars argue that how we perceive the world is highly dependent on our concepts (or our words) and beliefs. American philosopher Charles Sanders Pearce noted that perception is really just a kind of interpretation or conclusion about reality, that there is no need to go beyond the usual observations of life in order to find many different ways of interpreting perception.

Ruth Benedict claims that "no one sees the world with intact eyes," and Edward Sapir argues that "even the relatively simple aspects of perception are much more dependent on social models that are grafted into us with words than we might assume." Wharf echoes them: “We analyze nature according to the lines established by our native languages ... [Everyone defines] the categories and types that we distinguish from the world of phenomena and which we do not notice because they are right in front of us.” Thus, the perception of the same phenomena in different cultures is primarily due to linguistic and cultural differences, and any cross-cultural ethnopsychological research involves the identification of these differences.

Researches of Herth Hofstede

Dutch psychologist Geert Hofstede revolutionized cultural research for IBM in the 1970s. Hofstede’s theory of cultural dimensions is not only a springboard for one of the most active research traditions in intercultural psychology, but also a commercially successful product included in textbooks on management and business psychology. His initial work showed that cultures differ in four dimensions: perception of power, avoidance of uncertainty, masculinity-femininity and individualism-collectivism. After the “Chinese Cultural Connection” expanded its research using local Chinese materials, he added a fifth dimension - the long-term orientation (originally called Confucian dynamism), which can be found in all cultures except Chinese. This discovery by Hofstede was perhaps the most famous example of a cross-cultural study of stereotypes. Even later, after working with Michael Minkov, using data from the World Price Research, he added a sixth dimension - indulgence and restraint.

Criticism of Hofstede

Despite its popularity, Hofstede's work was called into question by some academic psychologists. For example, the discussion of individualism and collectivism in itself turned out to be problematic, and Indian psychologists Sinha and Tripati even argue that strong individualistic and collectivist tendencies can coexist within a single culture, citing India as an example.

Clinical psychology

Among the types of cross-cultural research, intercultural clinical psychology is perhaps the most prominent. Cross-cultural clinical psychologists (e.g., Jefferson Fish) and counseling psychologists (e.g., Lawrence H. Gerstein, Roy Modley and Paul Pedersen) have applied the principles of cross-cultural psychology to psychotherapy and counseling. For those who want to understand what a classic cross-cultural study is, the articles of these experts will be a true revelation.

Cross-cultural counseling

The book by Uwe P. Gilen, Juris G. Dragoons, and Jefferson M. Fish, entitled “Principles of Multicultural Counseling and Therapy,” contains numerous chapters on incorporating cultural differences in counseling. In addition, the book states that cross-cultural practices are already beginning to be included in counseling practices in various countries. The countries listed include Malaysia, Kuwait, China, Israel, Australia, and Serbia.

Five-factor personality model

A good example of cross-cultural research in psychology is an attempt to apply a five-factor personality model to people of different nationalities. Can the common features defined by American psychologists spread among people from different countries? In connection with this problem, intercultural psychologists often wondered how to compare features between cultures. To study this issue, lexical studies were conducted that measure personality factors using adjective attributes from different languages. Over time, these studies came to the conclusion that the factors of extraversion, harmony and good faith almost always appear the same among all nationalities, but sometimes there are difficulties with neuroticism and openness to experience. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether these traits are missing in certain cultures or whether different sets of adjectives must be used to measure them. However, many researchers believe that the five-factor personality model is a universal model that can be used in intercultural studies.

Differences in subjective well-being

The term "subjective well-being" is often used in all psychological studies and consists of three main parts:

- Satisfaction with life (cognitive assessment of shared life).

- The presence of positive emotional experiences.

- Lack of negative emotional experiences.

In different cultures, people may have polar notions of an “ideal” level of subjective well-being. For example, according to some cross-cultural studies, Brazilians put the presence of vivid emotions in life in the first place, while for the Chinese this need was in last place. Therefore, when comparing ideas about well-being in different cultures, it is important to consider how individuals within the same culture are able to evaluate various aspects of subjective well-being.

Level of satisfaction with life in different cultures

It is difficult to determine a universal indicator of how much the subjective well-being of people in different societies changes over a period of time. One of the important topics is that people from individualistic or collectivist countries have polar notions of well-being. Some researchers noted that representatives of individualistic cultures on average are much more satisfied with life than representatives of collectivist cultures. These and many other differences are becoming more understandable thanks to innovative scientists conducting cross-cultural research in psychology.