Some phrases and phrases do not mean at all what would result from a simple addition of the words used. Why can one and the same sentence be understood differently if we rearrange the semantic stress from one word to another? If the sentence is in context, then the words surrounding it usually provide explanations that help not to make a mistake. But sometimes the right conclusion is very difficult. In addition, this greatly complicates the perception of information, because it takes too much effort to arrange pieces of sentences and phrases in places. Given the problems of explanation and perception, it is important to separate the syntactic and actual division of the sentence.

If you do not immediately understand which member of the sentence is the main one, and which one is dependent, and what the speaker makes a statement on the basis of already known facts and what he wants to present as unique information, you will not get a quick reading or a standing dialogue with interlocutor. Therefore, when setting out it is better to coordinate your words with some rules and established norms inherent in the language used. Arguing in the opposite direction, the assimilation process will be easier if you become familiar with the principles of logical formation of sentences and the most common cases of use.

Syntax and semantics

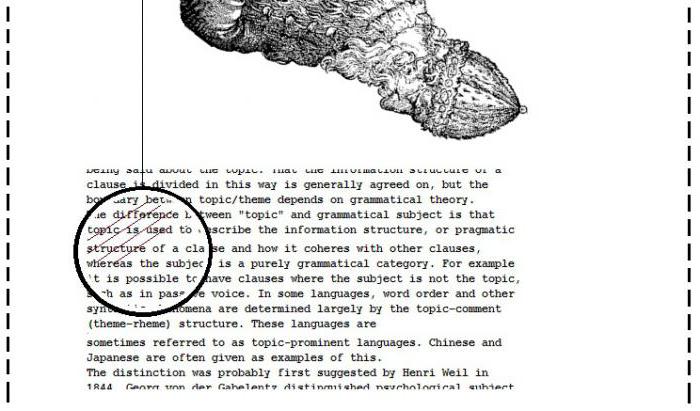

We can say that the actual division of sentences - this is the logical connections and accents, or rather, their explanation or discovery. Misunderstandings often arise when communicating even in the native language, and if it comes to operations with a foreign language, it is necessary, in addition to standard problems, to take into account differences in culture. In different languages, one or another word order traditionally prevails and the actual division of the sentence should take into account cultural characteristics.

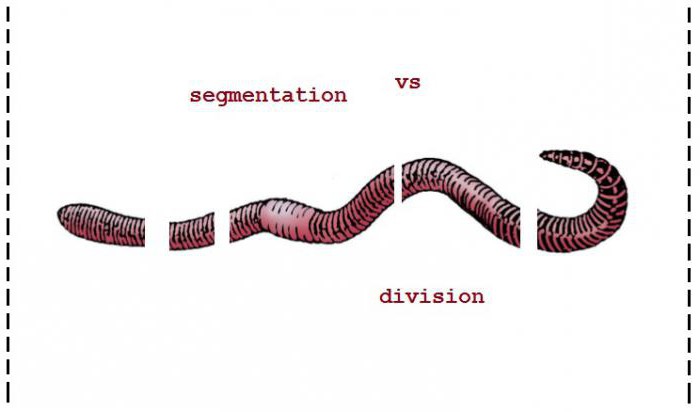

If you think in broad categories, all languages can be divided into two groups: synthetic and analytical. In synthetic languages, many parts of speech have several word forms that reflect the individual characteristics of an object, phenomenon or action relative to what is happening. For nouns, these are, for example, the meanings of gender, person, number and case; for verbs, such indicators are tenses, declension, mood, conjugation, perfection, etc. Each word has an ending or suffix (and sometimes even a root change) that corresponds to the function that is performed, which allows morphemes to react sensitively to the climate changing in the sentence. The Russian language is synthetic, because in it the logic and syntax of phrases rely heavily on the variability of morphemes, and combinations in absolutely any order are possible.

There are also isolated languages in which each word corresponds to only one form, and the meaning of the statement can be conveyed only through the means of expressing the actual division of the sentence as the right combination and sequence of words. If you rearrange parts of the sentence in places, the meaning can dramatically change, because the direct connections between the elements are broken. In analytical languages, parts of speech can have word forms, but their number, as a rule, is much lower than in synthetic ones. Here there is some compromise between the immutability of words, the rigidly fixed word order and flexibility, mobility, and interrelation.

Word - phrase - sentence - text - culture

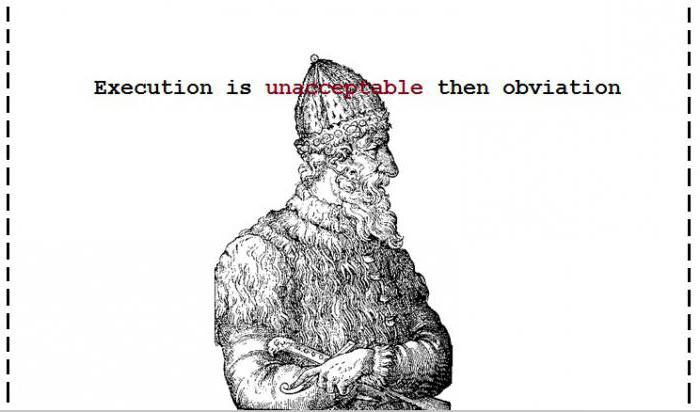

Actual and grammatical division of sentences mean that practically a language has two sides - firstly, semantic load, that is, logical structure, and secondly, actual mapping, that is, syntactic structure. This applies equally to elements of different levels - to individual words, phrases, phrase phrases, sentences, context of sentences, to the text as a whole and to its context. The semantic load is of paramount importance - for it is obvious that, by and large, this is the only goal of the language. However, the actual mapping cannot exist separately, since, in turn, its sole purpose is to ensure the correct and unambiguous transmission of the semantic load. The most famous example? "Execution cannot be pardoned." In the English version, it may sound like this: “Execution is unacceptable then obviation” (“Execution, is unacceptable then obviation”, “Execution is unacceptable then, obviation”). For a correct understanding of this instruction, it is necessary to determine whether the actual members of the group are “execute”, “cannot be pardoned” or the group “cannot be executed”, “have mercy”.

In this situation, it is impossible to draw a conclusion without syntactic indications of that - that is, without a comma or any other punctuation mark. This is true for the existing order of words, but if the sentence looked like "you can’t execute pardon," it would be possible to draw a corresponding conclusion based on their location. Then “execute” would be a direct indication, and “no mercy” - a separate statement, because the ambiguity of the position of the word “impossible” would disappear.

Subject, Rema and Division Units

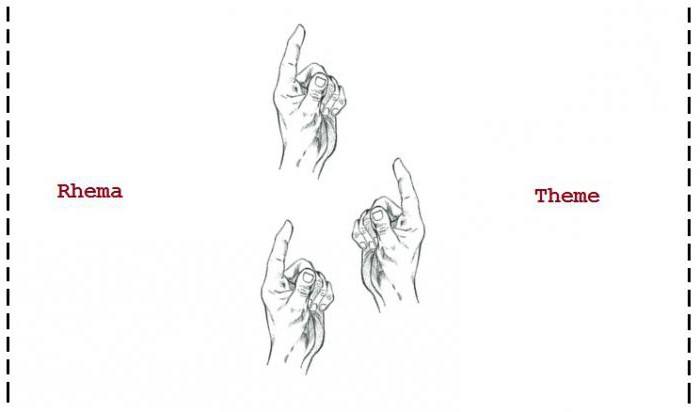

Actual division of sentences involves the division of the syntactic structure into logical components. They can be either members of a sentence or blocks of words that are closely united in the meaning of the word. Commonly used terms such as topic, rema and unit of division to describe the means of actual division of the sentence. Subject - this is already known information, or the background part of the message. Rema is the part on which emphasis is placed. It contains fundamentally important information, without which the proposal would lose purpose. In Russian, rema, as a rule, is at the end of the sentence. Although this is not unambiguous, in fact, the bump can be located anywhere. However, when a rema is located, for example, at the very beginning of a sentence, nearby phrases usually contain either a stylistic or semantic reference to it.

The correct definition of the theme and theme helps to understand the essence of the text. The units of division are words, or indivisible phrases within the meaning. Elements that complement the picture with details. Their recognition is necessary in order to perceive the text not by word of mouth, but through logical combinations.

"Logical" subject and "logical" addition

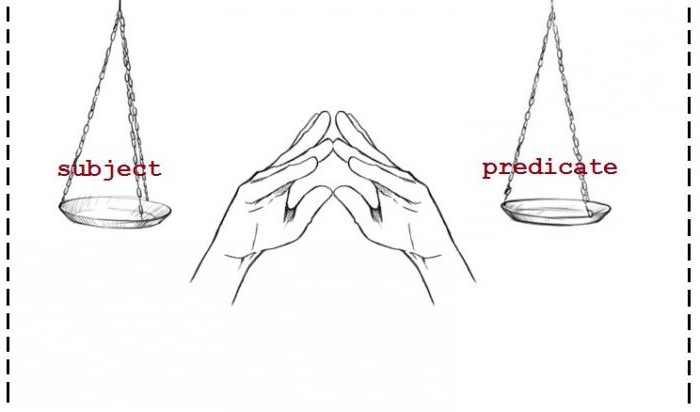

In the sentence there is always a subject group and a predicate group. The subject group explains who performs the action or whom the predicate describes (if the predicate expresses a state). The predicate group speaks of what the subject does, or in one way or another reveals its nature. There is also an addition that is attached to the predicate - it points to an object or living object to which the action of the subject passes. Moreover, it is not always easy to understand what is subject and what is an addition. The subject in the passive voice is a logical complement - that is, the object over which the action is performed. A supplement takes the form of a logical agent - that is, the one who performs the action. The actual division of the sentence in English identifies three criteria by which you can verify that there is a subject and that there is an addition. First, the subject is always consistent with the verb in the person and number. Secondly, it, as a rule, takes a position before the verb, and the addition - after. Thirdly, it carries the semantic role of the subject. But if reality contradicts any of these criteria, then, first of all, consistency with the verb group is taken into account. In this case, the complement is called the “logical” subject, and the subject, respectively, the “logical complement”.

Disputes over the predicate group

Also, the actual division of a sentence gives rise to a lot of controversy over what to consider as a group of a predicate - the verb itself, or the verb and its related additions. This is complicated by the fact that between them sometimes there is no clear boundary. In modern linguistics, it is generally accepted that the predicate, depending on the grammatical scheme of the sentence, is either the verb itself (main verb), or the verb itself with auxiliary and modal verbs (modal verbs and auxiliaries), or the linking verb and the nominal part of the compound predicate , and the rest is not part of the group.

Inversions, idioms and inversions as idioms

The thought that our utterance should convey is always concentrated at a certain point. Actual division of the proposal is designed to recognize that this point is a peak and attention should be focused on it. If the emphasis is incorrect, misunderstanding or misunderstanding of the idea may occur. Of course, there are certain grammatical rules in the language, however, they describe only the general principles of the formation of structures and are used for template construction. When it comes to the logical arrangement of emphasis, we are often forced to change the structure of speech, even if it is contrary to the laws of education. And many of these syntactic deviations from the norm have acquired the status of “official”. That is, they are fixed in the language, and are actively used in normative speech. Such phenomena occur when they free the author from resorting to more complex and excessively bulky constructions, and when the goal sufficiently substantiates the means. As a result, speech is enriched with expressiveness and becomes more diverse.

Some idiom turns could not be conveyed as part of the standard operation of the sentence members. For example, actual division of a sentence in English takes into account a phenomenon such as the inversion of sentence members. Depending on the expected effect, it is achieved in various ways. In a general sense, inversion means moving members to an unusual place. As a rule, subject and predicate become participants in inversions. Their usual order is this - subject, then predicate, then complement and circumstance. In fact, interrogative constructions are also inversions in a sense: part of the predicate is carried forward of the subject. As a rule, its meaningless part is transferred, which can be expressed by a modal or auxiliary verb. The inversion here serves the same purpose - to make a semantic emphasis on a specific word (group of words), to draw the attention of the reader / listener to a specific part of the statement, to show that this sentence is different from the statement. It’s just that these transformations have existed for so long, have come into use so naturally, and are so universally applied that we no longer treat them as something out of the ordinary.

Rheumatic secondary members

In addition to the usual inversion of the subject-predicate, there may be an introduction to the foreground of any member of the proposal - a definition, circumstance or addition. Sometimes it looks quite natural and is provided for by the syntactic structure of the language, and sometimes it serves as an indicator of a change in the semantic role, and entails a rearrangement of the other participants in the phrase. The actual division of the sentence in English suggests that if the author needs to focus on any detail, he puts it in the first place, if it cannot be singled out intonationally, or if it can be distinguished, but under certain conditions ambiguity may arise. Or, if the author simply does not have enough effect, which can be obtained by intonation. In this case, often in a grammatical basis, rearrangements of the subject and action also occur.

Word order

To talk about various kinds of inversions as a means of highlighting one or another part of a sentence, you need to consider the standard word order and the actual division of the sentence with a typical, template approach. Since the members often consist of several words, and their meaning should be understood only in the aggregate, it will also be necessary to note how the composite members are formed.

In the standard scenario, the subject always comes before the predicate. It can be expressed by a noun or a pronoun in the general case, gerund, infinitive, and subordinate clause. The predicate is expressed through the verb in the form of the actual infinitive; through a verb that does not in itself carry a specific meaning with the addition of a semantic verb; through an auxiliary verb and a nominal part, represented, as a rule, by a noun in the general case, a pronoun in the object case, or an adjective. As an auxiliary verb , a conjugated verb or a modal verb can be used. The noun can also be expressed equally by other parts of speech and phrases.

The cumulative meaning of phrases

The theory of actual division of a sentence suggests that a unit of division, correctly defined, helps to reliably find out what the text says. In combinations of words, they can acquire a new, unusual, or not entirely characteristic for them individually meaning. For example, prepositions often change the content of a verb; they give it many different meanings, up to the opposite. Definitions, which can be completely different parts of speech, and even subordinate clauses, specify the meaning of the word to which they are attached. Concretization, as a rule, limits the range of properties of an object or phenomenon, and sets it apart from the mass of people like it. In such cases, the actual division of sentences must be done carefully and carefully, because sometimes the connections are so twisted and erased by time that associating an object with any class, relying only on part of the phrase, significantly distances us from the actual essence.

The unit of division can be called such a fragment of the text that without loss of contextual connections can be determined using hermeneutics - that is, which, acting as a whole, can be rephrased or translated. Its significance may deepen, in particular, or be located on a more superficial level, but not deviate from its direction. For example, if we are talking about moving up, then it should remain moving up. The nature of the action, including physical and stylistic features, is preserved, but there remains freedom in the interpretation of details - which, of course, is best used to bring the resulting version as close as possible to the original, to reveal its potential.

Search for logic in context

The difference in syntactic and logical division is as follows - from the point of view of grammar, the most important member of the sentence is the subject. In particular, the actual division of sentences in the Russian language is based on this statement. Although, from the standpoint of some modern linguistic theories, such is the predicate. Therefore, we take a generalized position, and say that the main member is one of the components of the grammatical basis. When, from the point of view of logic, any member can turn out to be the central figure.

The concept of actual division of a sentence implies by the main figure that this element is a key source of information, a word or phrase, which, in fact, prompted the author to speak (write). It is also possible to hold more extensive connections and parallels, if we take the statement in context. As we know, the grammar rules in the English language regulate that the subject and the predicate must be present in the sentence without fail. If it is not possible or necessary to use the present subject, the formal subject is used, which is present in a grammatical basis as an indefinite pronoun, for example - “It” or “there”. However, the sentences are often consistent with the neighboring ones and are included in the general concept of the text. Thus, it turns out that the members can be omitted, even such important ones as the subject or predicate, irrational for the overall picture. In this case, the actual division of sentences is possible only outside the points and exclamation points, and the acceptor is forced to go for clarification in the surrounding neighborhood - that is, in the context. Moreover, in the English language there are examples when, even in the context, there is no tendency to disclose these members.

In addition to special cases of use in narratives, in ordinary order, such manipulations are engaged in indicative sentences (Imperatives) and exclamations. Actual division of a simple sentence is not always simpler than in complex constructions due to the fact that members are often omitted. In exclamations in general only one single word can be left, often interjection or a particle. And in this case, in order to correctly interpret the statement, one must turn to the cultural features of the language.