The fate of man is determined, as many believe, by his character. The biography of Shalamov is difficult and extremely tragic - a consequence of his moral views and beliefs, the formation of which was already taking place in adolescence.

Childhood and youth

Varlam Shalamov was born in Vologda in 1907. His father was a priest, a man expressing progressive views. Perhaps the environment that surrounded the future writer, and the parent's worldview gave the first impetus to the development of this extraordinary personality. There were exiled prisoners in Vologda, with whom Varlam's father always sought to maintain relations and provided all kinds of support.

Shalamov’s biography is partially reflected in his story “The Fourth Vologda”. Already in his youth, the thirst for justice and the desire to fight for it at any cost began to take shape in the author of this work. The ideal of Shalamov in those years was the image of a popular volunteer. The sacrifice of his deed inspired the young man and, possibly, predetermined the whole future fate. Artistic talent manifested in him from an early age. At first, his gift was expressed in an irresistible desire for reading. He read voraciously. The future creator of the literary cycle about the Soviet camps was interested in various prose: from the adventure novels of Alexander Dumas to the philosophical ideas of Immanuel Kant.

In Moscow

The biography of Shalamov includes the fateful events that occurred during the first period of stay in the capital. He left for Moscow at the age of seventeen. At first he worked as a tanner in a factory. Two years later, he entered the university at the Faculty of Law. Literary activity and jurisprudence are at first glance incompatible directions. But Shalamov was a man of action. The feeling that the years passed in vain tormented him already in his early youth. As a student, he was a member of literary disputes, rallies, demonstrations, and poetry evenings.

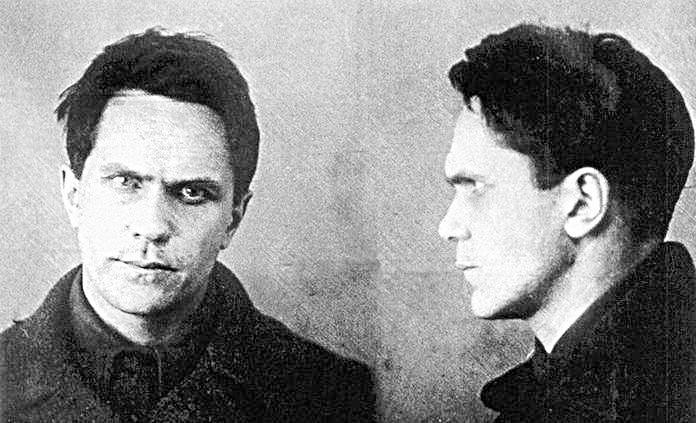

First arrest

Shalamov's biography is all about imprisonment. The first arrest took place in 1929. Shalamov was sentenced to three years in prison. Essays, articles, and many feuilletons were created by the writer in that difficult period that came after returning from the Northern Urals. To survive the long years of his stay in the camps, perhaps, the conviction that all these events were a test gave him strength.

Regarding the first arrest, the writer in autobiographical prose once said that it was this event that laid the foundation for a real public life. Later, having bitter experience behind him, Shalamov changed his views. He did not already believe that suffering purifies a person. Rather, it leads to the corruption of the soul. He called the camp a school, which has an extremely negative effect on anyone from the first to the last day.

But the years that Varlam Shalamov spent on Visher, he could not reflect in his work. Four years later, he was again arrested. Five years of the Kolyma camps became the sentence of Shalamov in the terrible 1937.

In Kolyma

One arrest followed another. In 1943, Shalamov Varlam Tikhonovich was taken into custody only because he called the emigre writer Ivan Bunin a Russian classic. This time, Shalamov survived thanks to the prison doctor, who at his own risk sent him to feldsher courses. On the key of Duskaniya, Shalamov began to write down his poems for the first time. After his release, he could not leave Kolyma for another two years.

And only after the death of Stalin Varlam Tikhonovich was able to return to Moscow. Here he met with Boris Pasternak. Shalamov’s personal life did not work out. For too long, he was cut off from his family. His daughter matured without him.

From Moscow, he managed to move to the Kalinin region and get a job as a master in peat mining. All free time from hard work was devoted to writing by Varlamov Shalamov. The Kolyma Tales, which the factory foreman and supply agent created in those years, made him a classic of Russian and anti-Soviet literature. The stories entered the world culture, became a monument to the countless victims of Stalinist repression.

Creation

In London, Paris and New York, Shalamov's stories were published earlier than in the Soviet Union. The plot of the works from the Kolyma Tales series is a painful depiction of prison life. The tragic fate of the heroes is similar to one another. They became prisoners of the Soviet Gulag by the merciless chance. Prisoners are exhausted and starved. Their further fate depends, as a rule, on the arbitrariness of bosses and thieves.

In "Tombstone" the author recalls the names of his dead comrades. He tells about the death of everyone, about the hopes and aspirations of those who died in the Soviet camp. Only a few managed to survive and preserve themselves morally.

Rehabilitation

In 1956, Shalamov Varlam Tikhonovich was rehabilitated. But his works still did not get into print. Soviet critics believed that in the work of this writer there is no "labor enthusiasm", but there is only "abstract humanism." Varlamov Shalamov took this review very hard. The Kolyma Tales, a work created at the cost of the author’s life and blood, turned out to be unnecessary to society. Only creativity and friendly communication supported spirit and hope in him.

The poems and prose of Shalamov were seen by Soviet readers only after his death. Until the end of his days, despite his poor health undermined by the camps, he did not stop writing.

Publication

For the first time, works from the Kolyma collection appeared in the writer's homeland in 1987. And this time, his incorruptible and harsh word was necessary for readers. It was no longer possible to safely go forward and leave the mass graves in Kolyma oblivion. The fact that the voices of even dead witnesses can be heard publicly, this writer proved. Shalamov’s books: “Kolyma Tales”, “Left Bank”, “Essays on the Underworld” and others are evidence that nothing has been forgotten.

Recognition and criticism

The works of this writer are one. Here is the unity of the soul, and the fate of people, and the thoughts of the author. The saga of Kolyma is the branches of a huge tree, small streams of a single stream. The storyline of one story smoothly flows into another. And in these works there is no fiction. They are only true.

Unfortunately, Shalamov’s work could only be appreciated by domestic critics after his death. Recognition in literary circles came in 1987. And in 1982, after a long illness, Shalamov died. But even in the postwar period, he remained an uncomfortable writer. His work did not fit into Soviet ideology, but it was alien to the new time. The thing is that in the works of Shalamov there was no open criticism of the authorities from which he suffered. Perhaps the Kolyma Tales is too unique in its ideological content to be able to put their author on a par with other figures of Russian or Soviet literature.