Reading the “Cursed Days” (Bunin, a brief summary follows), you involuntarily catch yourself thinking that in Russia one “cursed days” are replaced by endless new ones, no less “cursed" ... Outwardly they seem to be different, but their essence remains the former - destruction, desecration, abuse, endless cynicism and hypocrisy, which do not kill, because death is not the worst outcome in this case, but cripples the soul, turning life into a slow death without values, without feelings with only immense emptiness. It becomes scary when you assume that something like this happens in the soul of one person. And if you imagine that the "virus" is multiplying and spreading, infecting millions of souls, destroying for the whole nation all the best and most valuable for decades? Creepy.

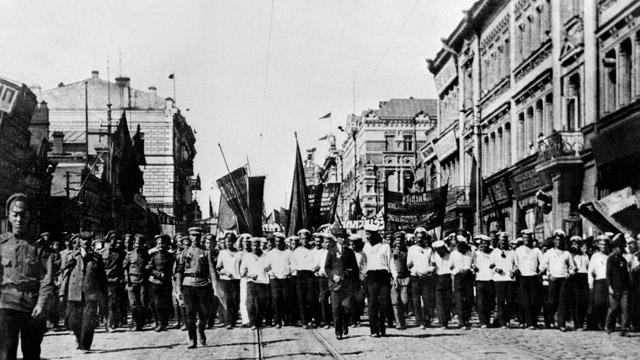

Moscow, 1918

From January 1918 to January 1920, the great writer of Russia Ivan Alekseevich Bunin ("Cursed Days") wrote down in the form of a diary - living notes of a contemporary - everything that happened before his eyes in post-revolutionary Russia, everything that he felt, experienced that he suffered and with what he never parted until the end of his days - an incredible pain for his homeland.

The initial recording was made on the first of January 1918. One “damned” year is behind, but there is no joy, because it is impossible to imagine what awaits Russia next. There is no optimism, and even any little malomsky hope for a return to the "former order" or early changes for the better melts with each passing day. In a conversation with the polishers, the writer quotes the words of a “curly-haired man” that today only God knows what will happen to us all ... After all, criminals and lunatics were released from prisons and psychiatric hospitals, who smelled of blood, endless power and impunity with their animals. “They imprisoned the Tsar”, attacked the throne and now rule a huge nation and atrocities in the vast expanses of Russia: in Simferopol, they say, soldiers and workers punish everyone indiscriminately, “they walk right down the knee in blood”. And the worst thing is that there are only a hundred thousand of them, and there are millions of people, and they can’t do anything ...

Impartiality

We continue the summary (“Cursed days”, Bunin I.A.). More than once the public, both in Russia and in Europe, accused the writer of the subjectivity of his judgments about those events, saying that only time can be impartial and objective in assessing the Russian revolution. Bunin answered unequivocally to all these attacks - there is no impartiality in its direct understanding and never will be, and his "partiality" suffered by him in those terrible years is the most impartiality.

He has every right to hate, and to gall, and to anger, and to condemnation. It is very easy to be “tolerant” when you observe what is happening from a far corner and you know that no one and nothing can destroy you or, even worse, destroy your dignity, mutilate your soul beyond recognition ... And when you find yourself in the thick of those same terrible events when you leave home and you don’t know whether you will return alive when you are evicted from your own apartment, when you are hungry, when you give them “an octopus of rusks”, “you shake them - the stink of hell, the soul burns”, when the most intolerable physical sufferings don’t go to what is the comparison with spiritual me mania and incessant, debilitating, taking out everything without a trace of the pain that “our children, grandchildren will not even be able to imagine the country, empire, Russia in which we once (that is, yesterday) we lived, which we did not appreciated, did not understand - all this power, complexity, wealth, happiness ... ”, then“ passion ”cannot but exist, and it becomes the very true measure of good and evil.

Feelings and emotions

Yes, Bunin's “Cursed Days” in brief are also filled with devastation, depression and intolerance. But at the same time, the dark colors that prevail in the description of people of those years, events and their own internal state can and should be perceived not with a minus sign, but with a plus sign. A black and white picture, devoid of bright, saturated colors, is more emotional and at the same time deeper and thinner. The black ink of hatred for the Russian revolution and the Bolsheviks against the background of white wet snow, "the schoolgirls stuck with it are coming - beauty and joy" - this is an agonizingly beautiful contrast, which at the same time conveys both disgust, and fear, and a true, incomparable love for the Fatherland , and the belief that sooner or later a “holy man”, “a builder of a high fortress” will overcome that very “buoy” and “destroyer” in the soul of a Russian person.

Contemporaries

The book “Cursed Days” (Ivan Bunin) is filled, and even overflowed, with the author’s statements about his contemporaries: Blok, Gorky, Himmer-Sukhanov, Mayakovsky, Bryusov, Tikhonov ... Judgments are mostly unkind and venomous. Could not I.A. Bunin to understand, accept and forgive their "slowness" before the new authorities. What could be the matter between an honest, intelligent man and the Bolsheviks?

What are the relations between the Bolsheviks and this whole company - Tikhonov, Gorky, Himmer-Sukhanov? On the one hand, they “fight” them, openly call them “the company of adventurers”, which, for the sake of power, cynically hiding behind “the interests of the Russian proletariat”, betrays their homeland and “atrocities on the vacant throne of the Romanovs”. And on the other? On the other hand, they live “at home” in the “National Hotel” requisitioned by the Soviets, on the walls are portraits of Trotsky and Lenin, and below is a guard from soldiers and a Bolshevik “commandant” issuing a pass.

Bryusov, Blok, Mayakovsky, who openly joined the Bolsheviks, and in general, according to the author, people are stupid. With the same zeal, they extolled both autocracy and Bolshevism. Their works are “simple”, quite “fence literature”. But what is most depressing is the fact that this “fence” is becoming the blood relatives of almost all of Russian literature, almost all of Russia is being protected by it. One thing is worrying - will it ever become possible to get out of this fence? The latter, Mayakovsky, can’t even behave decently, all the time it is necessary to “exhibit”, as if “boorish independence” and “steroos directness of judgments” are indispensable “attributes” of talent.

Lenin

We continue the summary - “Cursed days”, Ivan A. Bunin. The image of Lenin is saturated with special hatred in the work. The author does not skimp on sharply negative epithets addressed to the “Bolshevik leader” - “insignificant”, “fraudulent”, “Oh, what an animal this is!” ... They said more than once, and leaflets were posted on the city that Lenin and Trotsky were ordinary “ bastards ", traitors, bribed by the Germans. But Bunin does not really believe in these rumors. He sees in them “fanatics” who faithfully believe in the “world fire”, and this is much worse, because fanaticism is frenzy, obsession, erasing the boundaries of the rational and putting on the pedestal only the object of his adoration, and therefore terror, and unconditional destruction of all disagreeing. The traitor Judas calms down after he receives the "well-deserved thirty pieces of silver", and the fanatic goes to the end. There was plenty of evidence for this: Russia was kept in continuous “heat”, terror did not stop, civil war, blood and violence were welcomed, since they were considered the only possible means of achieving the “great goal”. Lenin himself was afraid of everything “like fire”, everywhere he “imagined conspiracies”, “trembled” for his power and life, because he did not expect and still could not fully believe in victory in October.

Russian revolution

“Cursed Days”, Bunin - the analysis of the work does not end there. The author also ponders a lot about the essence of the Russian revolution, which is inextricably linked with the soul and character of the Russian man, "for truly God and the devil are constantly changing in Russia." On the one hand, since ancient times, Russians have been famous for their "robbers" of various "bruises" - "rods, Murom, Saratov, Yaryig, runners, rebels against everyone and everything, sowers of all kinds of welds, lies and unfulfilled hopes." On the other hand, there was a “holy man”, and a plowman, and a hard worker, and a builder. Either there was an “incessant struggle” with buoys and destroyers, then an amazing admiration for “all kinds of weld, seditious, bloody turmoil and absurdity” was revealed, which unexpectedly equated to “great grace, novelty and originality of future forms”.

Russian bacchanalia

What caused such a blatant absurdity? Based on the work of Kostomarov, Solovyov about troubled times, on the thoughts of F. M. Dostoevsky, I. A. Bunin sees the origins of all kinds of turmoil, hesitation and precariousness in Russia in spiritual darkness, youth, discontent and imbalance of the Russian people. Russia is a typical country of Buyan.

Here, Russian history “sins” with extreme “repeatability”. After all, there was Stenka Razin, and Pugachev, and Kazi-Mulla ... The people, as drawn by a thirst for justice, extraordinary changes, freedom, equality, an imminent increase in welfare, and who did not understand much, rose and walked under the banners of those same leaders, liars, impostors and ambitious people. The people were, as a rule, the most diverse, but at the end of any “Russian orgy” the majority were fugitive thieves, idlers, bastards, and black people. The original goal is no longer important and has long been forgotten - to the point of destroying the old order and erecting a new one in its place. Rather, ideas are erased, and slogans are preserved to the end - it is necessary to somehow justify this chaos and darkness. Allowed full robbery, complete equality, full will from all law, society and religion. On the one hand, people become drunk from wine and blood, and on the other, they prostrate themselves in front of the "leader", because for the slightest disobedience, anyone could be punished by a cruel death. The "Russian Bacchanalia" surpasses everything in its scope, the former. The scale, "meaninglessness" and the special, incomparable blind, gross "ruthlessness" when "the good are taken away from the good, from the evil are untied for all evil" - these are the main features of the Russian revolution. And this is precisely what arose again on a huge scale ...

Odessa, 1919

Bunin I.A., “Cursed Days” - a brief summary of the chapters does not end there. In the spring of 1919, the writer moved to Odessa. And again, life turns into an unceasing expectation of a quick end. In Moscow, many were waiting for the Germans, naively believing that they would intervene in the internal affairs of Russia and free it from the Bolshevik gloom. Here, in Odessa, people are constantly running to Mykolayiv Boulevard - is there a French destroyer, graying in the distance. If yes, then there is at least some kind of protection, hope, and if not, horror, chaos, emptiness, and then all is over.

Every morning begins with reading the newspapers. They are full of rumors and lies, it accumulates so much that it is possible to suffocate, but whether it rains, cold, all one author runs and spends the last money. What is Petersburg? What is in Kiev? What is Denikin and Kolchak? Unanswered questions. Instead, there are flashy headlines: “The Red Army is only forward!” We are walking together from victory to victory! ” or “Go ahead, dear ones, do not count the corpses!”, and beneath them, calm, slender, as if it were necessary, notes about the endless executions of enemies of the Soviets or “warnings” about an imminent blackout due to complete depletion of fuel. Well, the results are quite expected ... In one month they “processed” everything and everything: “no railways, no trams, no water, no bread, no clothes - nothing!”

The city, once noisy and joyful, all in the dark, except for places where "Bolshevik dens" are "lodged". There, chandeliers glow with all their might, perky balalaikas are heard, black banners are visible on the walls, against which white skulls with the slogans: “Death to the bourgeois! But terribly not only at night, but also during the day. Out on the street a little. The city does not live, the whole huge city sits home. There is a feeling in the air that the country has been conquered by another people, some kind of special people, which are much worse than any hitherto seen. But this conqueror staggers around the streets, plays harmonies, dances, “obscenities”, spits seeds, trades from trays, and on his face, this conqueror, first of all, has no routine, no simplicity. It is completely sharply repulsive, frightening with its evil dullness and destroying all living things with its "gloomy and at the same time lackey" challenge to everything and everyone ...

“Cursed Days”, Bunin, summary: conclusion

In the last January days of 1920, I. A. Bunin and his family fled from Odessa. The diary pages were lost. Therefore, Odessa notes at this point break off ...

In conclusion of the article “Cursed Days”, Bunin: a brief summary of the work, I would like to give another words of the author about the Russian people, which, despite his anger, righteous anger, loved and revered immensely, because he was inextricably linked with his Fatherland - Russia . He said that in Russia there are two types of people: in the first, Russia dominates, in the other - Chud. But in one and in the second there is an amazing, sometimes terrible changeability of moods and looks, the so-called "precariousness". From it, the people, as from a tree, both a club and an icon can come out. It all depends on the circumstances and who cuts this tree: Emelka Pugachev or Rev. Sergius. I. A. Bunin saw and loved this “icon”. Many believed that he hated only. But no. This anger from love was also from suffering, so endless, so fierce that a real abuse of it occurs. You see, but you can’t do anything.

Once again, I want to remind you that the article talked about the work "Cursed Days", Bunin. The summary cannot convey the full subtlety and depth of the author’s feelings, so reading the diary notes in full is absolutely necessary.