The Cossack plastunas were some of the best scouts in the Russian army. They also arranged sabotage in the camp of the enemy. Plastuns left a serious mark in the history of Russian-Turkish wars and wars in the Caucasus. This variety of Cossacks at all times was considered not only elite, but also the most effective.

Scouts underwent lengthy training, which gave them a huge amount of useful and unique skills. Plastuns disappeared after the defeat of the Cossacks by the Bolsheviks. Nevertheless, the memory of them survived the 20th century. Even in the Soviet Union during the years of World War II, plastunsky units were created in which they tried to restore the structure of the legendary trackers.

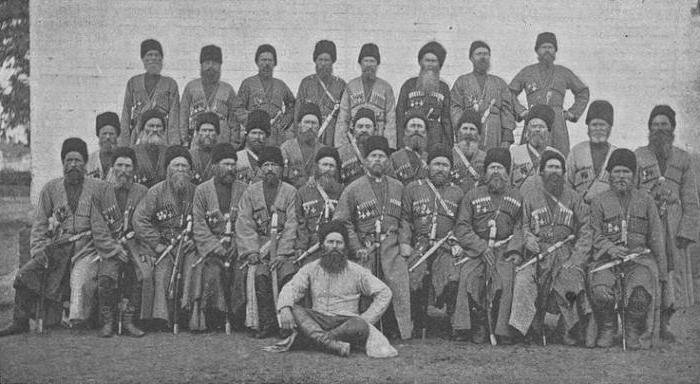

Thunderstorm Highlanders

In the 19th century, a separate layer of infantry — Cossack plastunas — stood out in the Cossack army. Their main task was reconnaissance. They should have warned their native villages about the approach of the Caucasian highlanders. For this, the so-called secret places were prepared in the border areas. It was in them that the plastunas served. Of these, Cossacks observed the cordon line. It was a series of posts, fortifications, pickets and batteries.

The most famous is the Black Sea cordon line, where the plastunas are especially famous. Cossacks erected fortifications on the right bank of the Kuban. Posts stretched from the Black Sea to the Adyghe Laba River. The cordon line was a place of constant skirmishes during the years of the Caucasian war. In this conflict, the plastunas declared themselves.

Cossacks defended the Kuban region from the raids of the Circassians, who previously owned the local lands. At first, the mountaineers made the life of the colonists unbearable. They burned villages, stole cattle, took civilians captive and robbed their property. Only the plastuns could stop the Circassians. Cossacks of this circle were armed with hatchets and threaded fittings.

Clothing and weapons

It is curious that a long neighborhood with the highlanders greatly influenced the life of the trackers. In peace periods, Cossacks and Circassians traded. Mixed families appeared, a gradual exchange of traditions took place. So the plastunas began to wear national Circassian clothing. A popular hat in their circle was a hat. Cossack clothes included pants with stripes and a shirt with shoulder straps. Its color depended on belonging to a particular army.

Widespread were wide hiking harem pants. Instead of shirts, plastunas could wear beshmets to their knees. Their notable features were mid-chest fasteners, padded collar and loose sleeves. Replacing the traditional hood accounted for the head. In reconnaissance, the plastunas wore clothes inconspicuous against the landscape. All kinds of tricks and disguises allowed to remain out of sight of the enemy. Of course, there were regional differences. For example, the Orenburg Cossack army, unlike its southern comrades, could not do without winter camping clothes, which helped keep warm in the cold and blizzards.

The fighting path of the plastunas quickly wore out their uniforms. Every day they spent in the wilds and gorges. The result of this lifestyle became frayed and covered with multi-colored patches Circassians. Another common attribute of a long hike was a red-haired and worn hat wrapped around the back of his head. Cossack shoes made by scouts became unremarkable in appearance, but extremely practical on a long journey. Often used duvy. They made them from the skin of wild boars.

In addition to the already mentioned weapons (cleaver, dagger and fitting), each plastun carried with him what the Kuban called “prichadaly”. These included: a bullet bag, a powder flask, an awl and a bowler hat. Everything that could help to survive a long journey was taken on the road, and at the same time it was distinguished by its small size and weight. Gradually, grenades became popular with plastunas. They were used in the most extreme case, if the detachment was overtaken by a numerically superior opponent.

At the Kuban borders

The field service of the plastuns lasted 22 years, then came a three-year period of service in the garrison. In the absence of open skirmishes with the highlanders, they were engaged in the maintenance of fortifications: they erected shapsugs, updated posts and batteries. These structures were quadrangular redoubts with a small moat and earthen parapet. At posts must have been artillery of various calibers. Another important attribute of Plastun places of service is observation tower. On the tower there were round-the-clock guards who, at the moment of danger, informed their comrades about the approach of the enemy.

The history of the plastuns was closely connected with the Kuban River. Every day, patrols drove along its shore, carefully watching the movements on the other side of the seething stream. Last but not least, the Highlanders were dangerous opponents due to the surprise of their attacks. That is why the service carried by the Kuban Cossacks-plastunas was so important.

Reconnaissance patrols (which usually consisted of 2-3 people) constantly changed their routes in order not to fall into an enemy ambush. In the event of the Circassian invasion, vanguard posts were abandoned. The Cossacks focused on the main cordon line. In addition, reinforcements from the rear rushed to their rescue. With the worst-case scenario, even those military who had already served 22 field years were drawn to the cordons. Most often, attacks were carried out on sections of the defense line remote from the sea. The channel of the Kuban was becoming narrower here, and numerous shallows and islets helped the mountaineers to make the crossing faster and more conveniently.

Professional skills

Often plastuns waited for uninvited guests, lying in a reed or swamp. It was from this intelligence habit that their name went. To clown is to crawl. The ability to remain inconspicuous was vital for scouts. Over time, their signature technique was postponed in the Russian language in the form of the phrase "crawl in the Plastunsky style." Researchers of the history of the Cossacks note that a similar masterful pressing to the ground appeared even among the Cossacks. The very word, having gained a household name, has been preserved in place names. For example, there is a village in Plastunovskaya in many regions of Russia and Ukraine.

Today, plastuns are considered the forerunners of modern Russian special forces. This comparison is not without reason very popular. These Cossacks had exactly the same functions: reconnaissance, sabotage, deep raids on the enemy rear. Often, plastuns were recruited from hunters who spent their whole lives in the forests. If any Cossack could be taught to handle weapons, then not everyone was given the ability to merge with the environment and become invisible at the most crucial moment.

To become a scout, it was not enough just to learn to crawl in a plastusky way. Cossacks from special units were able to remember each path, navigate in a wild unfamiliar area, cross the river through a stormy river. They had a hunting savvy, the ability to track and neutralize the target. Sometimes such chases could stretch for several days, so the Cossack knife of the plastun was given only to the most hardy and capable men.

Responsibilities and Privileges

For the first time, as separate units, the plastuns entered the regular regiments in 1842. One such team could include from 60 to 90 people. Immediately after their appearance, the Plastun troops began to enjoy special respect in the army. Their life was extremely dangerous even by Cossack standards. Because of this, the plastuns were entitled to increased salaries. If the Kuban went on a large campaign, then these scouts marched at the forefront, exploring the route along which the main army was to pass soon.

The most convenient time for the plastunas was always night. Their “Cossack uniform” (poor mountain clothing replaced it during the campaign) was not visible in the dark, and the ability to maintain silence allowed the scouts to make their way to enemy camps. Often, daredevils eavesdropped on conversations of opponents and found out their plans. For the army, all these services were invaluable.

Experienced plastunas knew the local customs of the highlanders. They understood the customs and customs of their dangerous neighbors. This knowledge helped to survive in captivity. In addition, the plastunas could even wear painted beards and impersonate "their". If at the same time the scout knew the necessary language and understood the realities of the enemy’s life, he could well penetrate the enemy’s camp. In the Caucasian languages, the word "kunak" exists today. So the Highlanders called their friends. Plastuns often had their kunaks among the Circassians and other neighboring indigenous peoples. They could report on moods and plans in their villages.

Training

Although there were cases when the plastunas were captured, they considered it a rule not to surrender to the enemy and in a hopeless situation they died at the scene of the battle. The courage of these warriors made them indispensable in the most difficult situations. During the siege by the enemy of important fortifications, the Cossack corps attracted the Plast to unlock these positions. The daredevils could, with a numerical superiority of the enemy, pull him over and scuff him, taking advantage of the positional advantages that the surrounding area gave. For example, the plastunas often opened fire from the forest. Such a sudden attack from nowhere by the enemy, as a rule, could not be calculated and cost him heavy losses. If the chase began, the Cossacks skillfully slipped out of the hands of the pursuers, hiding in the thickets and swamps. In addition, they were able to arrange effective ambushes, which even more mowed down the ranks of the enemy.

Plastunas trained in their midst, their community always remained somewhat isolated. Even when their status became official, scouts were not appointed, but elected among the "old men" - the most experienced and respected masters of their craft. It was they who passed on important and unique knowledge of the plastoons from generation to generation. Often this skill became a family affair. So, for example, the Black Sea plastuns were often recruited from among the hunting dynasties, consisting of several generations. Candidates went through a serious selection. Particular attention was paid to their stamina and accuracy.

Tactics

Young people with insufficient physical fitness were not taken to plastunas. These Cossacks should have been able to make exhausting march-throws in a wooded and mountainous area. Their combat path passed through the heat, cold and numerous inconveniences associated with camping life. All this required a remarkable composure and self-confidence from the candidate. Patience was especially needed at the crucial moment when tracking the enemy. Observing the enemy, scouts could lie for hours in reeds or even ice water. At the same time, emitting an extra sound for them meant jeopardizing not only their own, but also comradely lives. The Cossack form could get frayed, get wet, deteriorate, but the endurance of the Cossacks themselves had to withstand all even the most unexpected tests.

They themselves called the tactics of the plastins “wolf mouth and fox tail”. It was built according to the nature of the terrain, tasks and features of the enemy. But, as a rule, the actions of the scouts were based on several unshakable principles: to remain invisible, to find the enemy first and masterfully lure him into an ambush. Raids plastunov failed if the Cossacks could not clean up their own tracks. At the same time, the opposite skill was appreciated. Good scouts knew how to track down an enemy hiding even in the thickest forest.

Crimean War

As mentioned above, for the first time, plastunas loudly declared themselves during the Caucasian war against the Highlanders. In the future, not a single armed conflict of Russia could do without them. So in the Crimean War, specialized plastun battalions took part. They were especially distinguished during the defense of Sevastopol and in the battles in Balaklava. Plastunas, among other defenders of the homeland, served in the legendary fourth bastion. Count Leo Tolstoy, who also sniffed gunpowder in the Crimean War, was one of the first to capture these Kuban people in fiction. Plastuns are mentioned in the famous "Sevastopol Stories" of the Russian classic.

Not only the Kubans, but also the Orenburg Cossack army and other camps sent their scouts to the Crimean War. Scouts from this number carried out especially dangerous sorties into the enemy’s trenches. They, with their characteristic accuracy and accuracy, got rid of sentries and guards before general attacks. In addition, the plastuns carried out sabotage and spoiled enemy weapons. It was thanks to these Cossacks that the Russian army knew in detail about the movements of the British and French. Often the patrols found out the location of mine traps set by enemy sappers. For the exploits in the Crimean War, many plastuns received the highest individual awards, and the 8th Plastun battalion became the owner of their own St. George banner.

In battle again

In the future, the intelligence units of the Cossacks have proven themselves in armed conflicts with the Ottoman Empire. Plastunas made themselves felt in the Far East when they were sent to fight the Japanese in 1904-1905.

Finally, Cossack Rangers participated in the First World War. They made a huge contribution to the success of the famous Brusilovsky breakthrough on the South-Western Front, where 22 Plastun battalions served. Many Cossacks from these formations became St. George cavaliers, and their names turned out to be symbols of courage and devotion to duty. However, it was then that the Kuban daredevils went through a fork that was disastrous for themselves. During the Civil War, most of them supported the White movement. Plastunas fought with the Bolsheviks in the Kuban and Don, participated in the attack on Moscow and in the battles for Ukraine. After the victory of the Soviet regime, the Cossacks were subjected to tremendous repression. Many of them were forced to emigrate, and those remaining in their homeland had to survive the processing of the Cheka. Cossack life and traditions were systematically destroyed. The traditional stanitsa economy was eliminated. The result of this policy was that in the 20s. Cossacks as a large sociocultural group disappeared. Together with them in the past were plastunas in the classical sense of the word. They lost their historical roots and foundations, their lifestyle was outlawed.

Soviet era

But already during the Great Patriotic War, the Soviet government changed its rhetoric. She tried to restore the Plastun traditions, and for this even the 9th Plastun Rifle Division was created. As a hello to the glorious past, a division into hundreds and battalions was introduced in it.

This Plastun division was included in the Separate Maritime Army. Its first operation was the defense of the Taman Peninsula. It is curious that it is in this region that there is a village of Plastunovskaya. The newly formed Cossack units and volunteer hundreds were distinguished by poor armament. Often hastily assembled cavalry had nothing but thin and frail collective farm horses. The squads lacked anti-aircraft guns, tanks, and sappers. All this led to heavy losses. According to eyewitnesses, the Cossacks jumped out of the saddles on tank armor. In addition, they did a lot of other dangerous rough work.

Then the Cossacks took part in the Crimean operation. The liberation of the peninsula began with the destruction of the Wehrmacht rearguards in the vicinity of Kerch in April 1944. For several months, the Cossack units were undergoing modernization. They united with cavalry divisions and tank units of the Red Army. As a result, horse-mechanized groups arose. Horses were used for fast movement, while in battle, the Cossacks acted as infantry. In modern Russia, the phenomenon of plastoons has undergone reevaluation and numerous studies. Today, Cossack organizations function throughout the country in which forgotten military traditions are being revived.