The modern Russian alphabet appeared as a result of the reform of Russian spelling in 1918, better known as the “Lunacharsky decree”. Grandiose spelling changes were necessary and prepared for a long time (even under the tsar), but the reform was perceived in the spirit of the times, that is, as revolutionary. Therefore, a serious discussion flared up around linguistic issues, in which politicians, philosophers, and philologists took part. The anniversary (100 years of the reform of Russian spelling in 2018) prompted a return to this topic.

A brief excursion into history

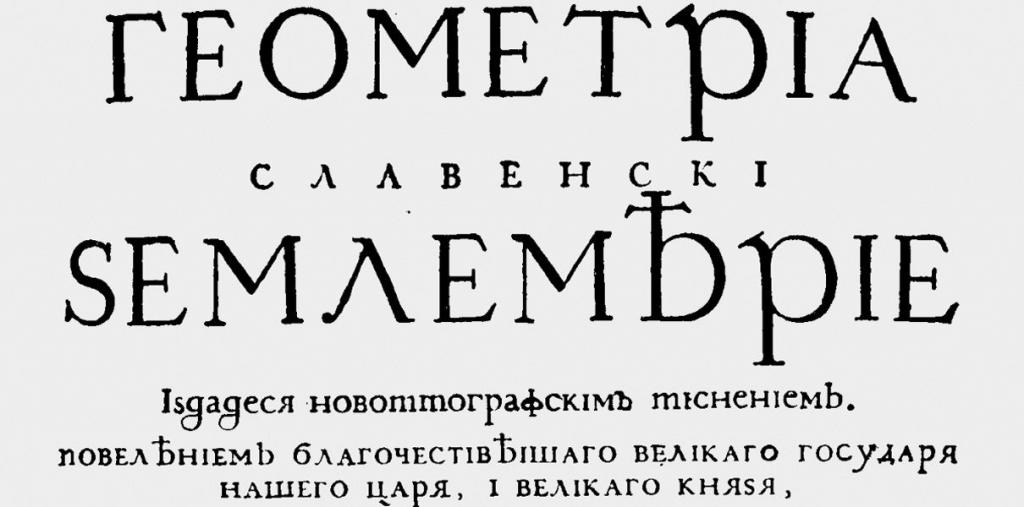

Pre-revolutionary Russian spelling in the main features took shape even during the time of the reformer Peter I. The All-Russian Emperor in 1707-1708 introduced instead of the Cyrillic alphabet the so-called “civil script”, which exists in a more simplified form even now, and removed several letters from the alphabet. This finally separated the sublime Church Slavonic language (high style) and crude colloquial speech (low style) and created the prerequisites for the formation of a middle style.

For reference: such a division existed before, since the language developed spontaneously. The bi-style of the Russian language was noted by Heinrich Wilhelm Ludolph - the author of the first Russian, or Russian, grammar in Latin, published in the UK in 1696. He wrote that Russians speak Russian and write in Slavic. Since the German philologist was guided by the spoken language, he compiled the grammar of the spoken language. He translated five dialogues on a domestic topic and one on a religious topic and noted that book, written and spoken language are different.

In practice, in the reform of Peter I, everything seems simple: the intricate outlines of letters have been replaced by clear and strict forms, the language has become clearer. There were no changes to a number of Russian spelling rules. But not only simplification happened. Firstly, it is of extreme importance that for the first time the development of the Russian language took place in the order of state reforms. Secondly, the reform did not come from philologists, that is, political goals were pursued. So, one of the main aspirations of Peter I was not the simplification and unification of Russian writing, but the separation of the church from the state, that is, secularization.

Spelling: from Peter I to Nicholas II

The middle style, laid down by Peter the Great, was subsequently formalized in the writings of Mikhail Lomonosov (the theory of the three "calm"). The middle style turned out to be the same literary language, 55% of which is borrowed from Church Slavonic, and less than 45% from Russian spoken. The rest is foreign borrowing. Then the creative genius of Alexander Pushkin synthesized into a single system the Russian folk dialect, Church Slavonic and Western European. The basis was the Moscow variety of Russian. It was with Pushkin that the all-Russian, that is, the phonetic, lexical, and grammatical norms binding on all who know the language, began.

After the appearance of a relatively stable spelling, almost immediately began to talk about the need to make changes. Academician Yakov Grot officially approved the rules of the Russian literary language. The basis of his work "Russian Spelling", published in 1885, was made up of phonetic and etymological (historical) principles. There was a constant conflict between these principles, which led to inconsistency in writing. The existence of conventional spelling was better than the spelling disorder of previous eras. But still society was hardly getting used to the rules of the Grotto.

The availability of writing not only for educated people could be ensured in two ways. It was necessary to linguistically simplify the schedule, that is, remove the extra letters and spelling rules. In matters of pedagogy, it was required to be more lenient with episodes of violation of the rules for spelling words, complex and difficult cases. In 1904, the tsarist government asked the Academy of Sciences to discuss the simplification of the grammar of Jacob Grotto. The editorial staff of the Academy replied that criticism of the Grotto’s works as a whole does not affect the interests of the institution. This meant that you could get to work.

How was Soviet spelling born?

So, in the twentieth century, the development of the literary language was again actively influenced by public and state figures. It becomes clear that the spelling reform of 1918 was being prepared and discussed long before its practical implementation. Many of the plans of Peter I did not find implementation, which is to say about the philological ideas accumulated during the period from the late seventeenth to the beginning of the twentieth century. Bolshevik linguists did not begin to develop a draft language reform immediately after the October Revolution, but took advantage of a ready-made project prepared by the Academy of Sciences in 1912.

The last Russian emperor Nicholas II drew attention to the need to simplify the language. Already in 1904, a commission was formed at the Academy of Sciences under the leadership of Phillip Fortunatov, one of the most significant pre-revolutionary linguists, the founder of the Moscow linguistic school. The chairman was A. Shakhmatov. The meeting, held in 1911 at the Academy, in general approved the preliminary draft. The commissions were instructed to develop in detail the main parts of the reform.

The reform was completely ready by 1912. It was planned to remove a large number of spelling rules from the Russian language: at the end of verbs and nouns it was no longer necessary to write a soft sign, in general a hard one was eradicated from the letter and so on. The first editions with new rules appeared in stores, but the main goal - the elimination of the total illiteracy of the population - was not achieved. After all, the tsarist Academy was initially guided not by political ideas (eradicating the heritage of past times, for example), but by the desire to simplify literacy for under-educated people.

Then the interim government began to reform the spelling of the Russian language. In short, they did not come up with anything new in this aspect. The consultative work dealt with many issues - local government reforms were planned, an agrarian, rather complicated scheme of reorganization of higher education - but in the institutes there was always free thought needed by the new government, therefore, much attention was paid to enlightenment. In practice, the matter was limited to the approval of the “tsarist” reform - the 1912 project.

Decree of the People's Commissar A. Lunacharsky

The Ministry of Education supported the reform and announced that starting from the new school year, all schools should move to the new rules. The main goal was to facilitate the assimilation of Russian literacy by the masses, that is, a very reasonable intention. Reform of Russian spelling in 1918 was mandatory only for the initial levels of the school, with regards to all the rest, retraining was not allowed. For all students and applicants, only those requirements that were common to the new and old spelling remained in force, violations of only these rules were considered errors.

A decree signed by the People’s Commissar for Education A. Lunacharsky determined the official press organ of the People's Commissars - “Newspapers of the Temporary Worker and Peasant Government”, which was to be published under the new spelling rules. But other periodicals in the territory controlled by the Soviet regime continued to be printed in the pre-revolutionary language. For example, the official publication of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee "Izvestia" only refused to use a solid sign, including a dividing one. The letter was replaced with an apostrophe, which went against the new requirements. So the party Pravda was printed.

The change in Russian spelling, finally formally formalized by a decree of October 15, 1918, published in Izvestia, was somewhat delayed. Government newspapers switched to a new writing only on October 19 of the same year, in the title - only after the 25th of the same month. The reform not only changed a number of rules of Russian spelling, but also served as an excellent occasion for ideological delimitation. From the moment of the decree, the refusal to use the new language has become a sign of rejection of the new government. During the war, for example, the new spelling was categorically not used in the territories of whites.

The content of the Russian language reform

In 1918, the new Soviet government excluded the solid sign, the letters “fita” and “and decimal” from the alphabet (they used “e”, “f”, “and” instead). The endings of the words in the accusative and genitive cases of the participles and adjectives have changed (instead of “early” it was now necessary to write “early”, instead of “new” - “new”). The word form of the genitive singular “her” changed to “her” (respectively: “her” to “her”). A solid sign at the end of the word was excluded. The rule for writing prefixes changed: before the deaf consonant it was necessary to write “c”, before the call - “z.” The solid sign (“b”) was saved only as a separator. The letter "Izhitsa", which came out of practical use before the revolution, was not mentioned at all in official documents. So, the reform of the Russian language of 1918 concerned not only spelling, but also orthoepy, grammar.

The exclusion of the letters "fita" and "yat"

This seems like the most harmless substitute, because the pronunciation of the letters in many cases coincides. But in a linguistic sense, the loss of “yat” in a language meant a loss of connection between Russian and other Slavic languages. The letter “fita” in Russian was borrowed from Greek to mean the Latin sound [th]. More often used and proper names (for example, the Russian "Fedor" corresponded to the name "Theodore", common in Catholic countries). As a result, Russian, not only graphically, but also in a semantic sense, moved away from Greek.

Spelling distortion

During the practical implementation of the reform of the Russian language of 1918, many native Russian words suffered. For example, earlier spelling distinguished the words “peace” in the meaning of “absence of war, peace, silence” and “peace” through “and” decimal in the meaning of “society, society”. So, the title of Leo Tolstoy's work “War and Peace” in the original spelling was interpreted as “War and Society”. The correct translation of the title into English should be Word and society, but the reform has reduced everything to Word and peace, which completely does not meet the author’s intention. The “worldview” was also affected, because after the reform of the Russian language of 1918, it was as if it was a view of not “society” (“world” through “and” decimal), but “peace” (“world” in modern spelling )

Hard Sign Exception

The solid sign at the end of the word and in the middle in antiquity was read as “o” or “a”. Such a linguistic situation has been preserved, for example, in modern Bulgarian. The name of the country is spelled “Bulgaria”, and reads like “Bulgaria” (by analogy: “ed” corresponds to “court”, “ad” means an angle, “pat” means a path and so on). This sound was found in Russian everywhere and was always written at the end of words after a solid consonant. But in Old Slavonic the word could not end with a consonant sound, therefore, at the end a solid sign ("b") was added, which was considered a vowel.

This caused a lot of trouble when printing. “Kommersant” was written in pre-revolutionary literature not in a line, but in one and a half, but was not read. In the epic novel “War and Peace” by Leo Tolstoy, with 2080 pages of typesetting, 115 thousand letters “b” were found. If all the solid characters, pointlessly scattered across the pages of a work, were put together and printed in a row at the end of the last volume, then this would take seventy-odd pages.

But books are not published in a single copy. Only one edition of War and Peace, numbering three thousand copies, is two hundred and ten thousand pages occupied by the letter "b". From such a number of pages, one could create two hundred and ten books with a thousand pages each. For comparison: a collection of short stories by P. Bazhov “Malachite Box” takes up less pages, “Mysterious Island” by J. Verne - 780.

A solid sign at the end of a word is not economical and unreasonable. But in those days, the rejection of the use of the letter "b" by many (especially adherents of the monarchy) was perceived as a rejection of the cultural tradition associated with Orthodoxy. The open syllable system, which previously dominated without exception, was also destroyed, and after that other examples of refusal of the syllable system became possible.

As for the dividing solid sign (the letter "yat"), it was allowed, but when the softness and gradual reform of the language were discarded. The revolutionary-minded sailors began to travel around the printing houses and seized letters prohibited by decree. So, in fact, according to the “legal” separation function, the hard sign could not be used either. They began to replace him with an apostrophe. This replacement was not part of the initial reform project, but was mistakenly perceived as part of it.

"I am to eat"

After the elimination of several letters in the language, confusion arose. Some of the words that are identical in sound but different in spelling (homophones) have turned into homonyms, that is, the same both in ear and in spelling. Representatives of the intelligentsia saw in this the intent of the Bolshevik authorities. Philosopher I. Ilyin, for example, argued that the same spelling “eat” in the meaning of “eat” and “eat” in the meaning of “exist” will create an orientation toward materiality. The word is used quite often. In the short work of Ilyin himself, “On the Russian Idea,” “is” (“to appear”) is used twenty-six times among three and a half thousand words. Confusion significantly impedes the understanding of the author’s thought by an unprepared reader. In fact, the is-is factor was hardly intent. Most likely, this was a side effect of major changes.

“And”: decimal and octal

The most dramatic change in the old system was the replacement of the decimal “and” (with a period, originally the Greek letter “iota”) with the octal (“and” modern). Prior to this, both options organically coexisted in the language. Was it wise to leave the octal “and”? The letter "iota" is the most recognizable sign of many European alphabets and is distinguished by its simplicity. This graphic symbol seems to be taken from a different set, and not from modern alphabets with complex characters.

The letter "i" really refers to the oldest set of graphics. From this position, “parting” was a great cultural loss. The withdrawal of "iota" from circulation is hardly justified for another reason either: psychologists drew attention to the fact that the simple symbol "i" allows to increase the speed of reading the font, reduces eye fatigue and speeds up word recognition.

Removing from the alphabet "izitsa"

In the Bolshevik decree there is no mention of a letter called "izhitsa", which was the last in the pre-revolutionary alphabet. By the time the reform was carried out in practice, this symbol was rare. It was possible to find “izhitsa” only in church texts. In civilian language, the letter was used only in the word "miro". But even the Bolsheviks rejected the "Izhitsa" many saw an evil omen: the Soviet government refused the sacrament of anointing, through which the gifts of the Holy Spirit are given to a religious person, which strengthen the faith. The official removal of “feats” and the undocumented elimination of “izitsa” made the last letter in the alphabet “I”. The intelligentsia saw in this the malevolence of the new government: they sacrificed in two letters to put in the end the one that reflects human personality.

The practical implementation of the reform

The reform of the Russian language of 1918 became directly associated with the Bolsheviks, largely due to the methods of its implementation. The ideological rejection of the new government was actively extended to new language rules. In Bolshevik Russia and the USSR there was nowhere to go especially, but in immigration everything was completely different. Ivan Bunin, for example, as one of the most ardent examples of rejection of the new spelling, categorically insisted on printing his works according to the old rules. Speaking generally about publishing policy, conservative publications sometimes literally stayed until the last issue. Even in the years 1940-1950. periodicals with the letters "yat" and "fita" came out.

Moreover, in Russia, the new government quickly established a monopoly on printed matter and monitored the implementation of the decree. It has become a private practice to remove prohibited letters from circulation. But until 1929, some scientific publications came out according to the previous spelling (excluding the title and foreword). It is also noteworthy that on the Soviet railways steam locomotives with series designations were eliminated from the alphabet. The situation did not resolve until the decommissioning of these cars in the 1950s.

Criticism of Spelling Reform

Even before the reform of the Russian language in 1918, critics expressed various objections. Some believed that no one has the right to forcibly make changes to established spelling, and only natural changes are permissible. Others pointed out that the changes were completely impossible in practice, because all classics and all textbooks needed to be reprinted at once, and the entire teaching staff and intelligentsia should immediately be ready to accept the new spelling. It just was not possible.

Despite the fact that the reform was developed under the tsarist government, it was introduced by the Bolsheviks, so it was perceived as part of the revolution. In this sense, the history of the reform of the Russian language of 1918 is even more interesting. Of course, the opponents of Bolshevism were critical of the changes. Everything remained the same in the territories controlled by whites, and in exile. Publications of the Russian foreign countries switched to the new rules only in the forties or later.

Linguists blamed the reform for inconsistency. The criticism of I. Ilyin, containing elements of both socio-political and linguistic, is widely known. Symbolist V. Ivanov criticized changes from an aesthetic perspective. He believed that the Russian language was not really simplified, but only made it more difficult, destroying the old foundations of spelling. The intelligentsia was puzzled by the question of why this mind-blowing simplification was needed at all. The answer (according to many philosophers and creative people) was simple: only to the enemies of Russia.

Future plans: latin alphabet

The Bolsheviks did not plan to stop there. In anticipation of the world revolution, it was proposed to introduce Latin letters at the official level. Then it was often said that there are too many letters in the Cyrillic alphabet, and the Latin alphabet consists of only twenty-six. This saves money on typography. Those who advocated the preservation of the Cyrillic alphabet were immediately ranked among the opponents of the Soviet regime.

In 1925, a special committee was created in Baku, which was engaged in the distribution of Latin letters in the USSR. The slogans of those years clearly reflect the aspirations of the authorities: "The Latin is the letter of October." A specialist in the languages of the Caucasus N. Yakovlev put a lot of effort into popularizing the Latin alphabet. Today, no one remembers him, but before the chairman of the commission was called the "great Latinizer" and "technographic commissar."

In 1930, a year after Yakovlev headed the commission for the development of Latin letters at the USSR Supreme Science, three projects were submitted. These alphabets were useful to Adolf Hitler in 1942 for propaganda in the occupied territories when the talented scientist N. Poppe signed up for his supporters. However, by the thirties, the efforts of the Latinizers were appreciated only by the well-known People's Commissar A. Lunacharsky. In his article “To the Latinization of the Russian Alphabet”, published in Krasnaya Gazeta in 1930, he recalled that Vladimir Lenin himself dreamed of a time when all Russian people would write in Latin letters. By the way, except for Lunacharsky himself, no one behind Lenin noticed such thoughts.

Mixed Reform Results

The results of Lunacharsky's changes in the early years of the young Soviet state were not unambiguous. There were positive aspects of the reform, but criticism was enough. On the one hand, modern Russian took shape, which has become much easier. At the same time, Russian is still very difficult for foreigners to study. On the other hand, politicians were ready to go further (Latinize), which would simplify the spread of the revolution to European states. But this desire was suppressed by the Bolsheviks.