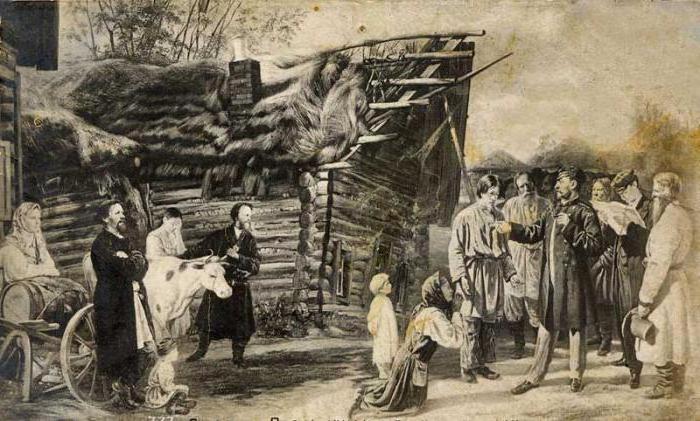

The existence of serfdom is one of the most shameful phenomena in the history of Russia. Nowadays, more and more often one can hear statements that the serfs lived very well or that the existence of serfdom favorably affected the development of the economy. Whatever these opinions may be for the sake of, they, to put it mildly, do not reflect the true essence of the phenomenon - absolute lawlessness. Someone will object that enough rights were assigned to serfs by legislation. But in reality they were not fulfilled. The landowner freely controlled the life of his people. These peasants were sold, gifted, lost on cards, tearing apart relatives. The child could be torn from the mother, husband from the wife. Such regions existed in the Russian Empire where serfs were especially tight. These regions include the Baltic states. The abolition of serfdom in the Baltic states took place during the reign of Emperor Alexander I. How everything happened, you will learn in the process of reading the article. The year 1819 became the year of the abolition of serfdom in the Baltic states. But we will start from the very beginning.

Baltic Region Development

No Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia in the Baltic lands at the beginning of the XX century did not exist. Courland, Estland and Livonia provinces were located there. Estonia and Livonia were captured by Peter the Great during the Northern War, and Russia managed to get Kurland in 1795, after the next partition of Poland.

The inclusion of these areas in the Russian Empire had a lot of positive consequences for them in terms of economic development. First of all, a wide Russian market opened up for local suppliers. Russia gained from joining these lands. The presence of port cities made it possible to quickly establish sales of Russian merchants.

Local landowners also did not lag behind Russian exports. So, St. Petersburg occupied the first place in the sale of goods abroad, and Riga took the second place. The main focus of the Baltic landowners made on the sale of grain. It was a very profitable source of income. As a result, the desire to increase these incomes led to the expansion of land used for stocking and to an increase in the time allotted to corvee.

Urban settlements in these places until the middle of the XIX century. hardly developed. They were of no use to the local landowners. Rather, it will be said that they developed one-sidedly. Purely like shopping centers. But the development of industry lagged significantly. This happened due to the very slow growth of the urban population. This is understandable. Well, who among the feudal workers will agree to let go of gratuitous labor. Therefore, the total number of local citizens did not exceed 10% of the total population.

The landowners created the manufacture themselves in their possessions. They also did business on their own. That is, the classes of industrialists and merchants in the Baltic states did not develop, and this affected the general movement of the economy forward.

A distinguishing feature of the Baltic territories was that the nobles who made up only 1% of the population were Germans, as well as the clergy and a few bourgeois. The indigenous population (Latvians and Ests), contemptuously called “non-Germans”, was almost completely powerless. Even living in cities, people could only rely on work as domestic workers and laborers.

Therefore, we can say that the local peasantry was doubly unlucky. Along with serfdom, they had to experience national oppression.

Features of the local corvee. Oppression gain

The corvee in local lands has traditionally been divided into ordinary and extraordinary. When an ordinary peasant had to work on the land of the landowner with his equipment and a horse the established number of days. The employee was supposed to appear by a certain date. And if the interval between these periods was small, then the peasant had to stay in the landowner lands all this time period. And all because, the traditional peasant households in the Baltic countries are farms, and the distances between them are very decent. So the peasant would just not have time to turn back and forth. And while he was in the sovereign lands, his arable land stood uncultivated. Plus, with this type of corvee, it was supposed to send from each farm for a period from the end of April to the end of September one more worker additionally, already without a horse.

The most developed in the Baltic states has received an extraordinary corvee. Peasants with this duty were obliged to work on the farm fields during seasonal agricultural work. This species was also divided into auxiliary corvée and general squalon. Under the second option, the landowner was obliged to feed the peasants throughout the entire time while they worked in his fields. And at the same time he had the right to drive the entire able-bodied population to work. Needless to say, for the most part the landowners did not comply with the law and did not feed anyone.

An extraordinary corvée was especially destructive for peasant farms. Indeed, at a time when it was necessary to plow, sow and harvest hastily, there was simply no one left on the farms. In addition to working in the fields, peasants were obliged on their carts to transport household goods to remote areas for sale and from each yard to deliver women to care for the master's cattle.

The beginning of the XIX century. for the agrarian development of the Baltic states is characterized by the development of farm laborers. Farm laborers are landless peasants who appeared as a result of the seizure of land by the landowners. Left without their economy, they were forced to work for more prosperous peasants. Both of these layers were related to each other with a certain degree of hostility. But they were united by a common hatred of the landlords.

Class unrest in the Baltic states

The Baltic met the beginning of the 19th century in the conditions of escalated class contradictions. Mass peasant uprisings, the escapes of serfs became a frequent occurrence. The need for change has become increasingly apparent. The ideas of abolishing serfdom and the subsequent transition to civilian labor more and more often began to sound from the lips of representatives of the bourgeois intelligentsia. It became obvious to many that the intensification of feudal oppression would inevitably lead to a large-scale peasant uprising.

Fearing the recurrence of revolutionary events in France and Poland, the tsarist government finally decided to turn its eyes to the situation in the Baltic states. Under his pressure, the noble assembly in Livonia was forced to raise the peasant question and legislate for the peasants the right to dispose of their own movable property. The Baltic landowners did not want to hear about any other concessions.

The discontent of the peasants grew. They were actively supported in the claims of the urban lower classes. In 1802, a decree was issued according to which the peasants were allowed not to send natural products in fodder supplies. This was done because of the famine that began in the region as a result of the crop failure of the previous two years. The peasants, by whom the decree was read, decided that the good Russian tsar now completely exempts them from work on corvee and dues, and local authorities simply hide from them the full text of the decree. Local landlords, having decided to compensate for the losses, decided to increase the worked corvee.

Wolmar Uprising

The beginning of the abolition of serfdom in the Baltic states (1804) was facilitated by some events. In September 1802, peasant unrest swept peasant farms in the area of the city of Valmiera (Wolmar). First, the laborers rebelled, who refused to go to the corvee. The authorities tried to suppress the rebellion by the forces of the local military unit. But that failed. The peasants, having heard of the uprising, hurried from all distant places to take part in it. The number of rebels increased every day. Gorhard Johanson, who, despite his peasant origin, was well acquainted with the work of German human rights activists and enlighteners, led the uprising.

On October 7, several instigators of the uprising were arrested. Then the rest decided to release them using weapons. The rebels in the amount of 3 thousand people concentrated in the estate of Kauguri. Of the weapons they had agricultural equipment (scythes, pitchforks), some hunting rifles and batons.

On October 10, a large military unit approached Kauguri. The rebels opened fire from artillery. The peasants were scattered, and the survivors were arrested. The leaders were exiled to Siberia, although initially they were going to execute them. And all because during the investigation it was revealed that the local landowners managed to distort the text of the decree on the abolition of taxes. The change of serfdom in the Baltic states under Alexander I had its own peculiarities. This will be discussed later.

Emperor Alexander I

The Russian throne during these years was occupied by Alexander I - a man who spent his whole life throwing between the ideas of liberalism and absolutism. His educator, Lagarpe, a Swiss politician, instilled in Alexander a negative attitude towards serfdom from childhood. Therefore, the idea of reforming Russian society occupied the mind of the young emperor, when at the age of 24 in 1801 he ascended the throne. In 1803, he signed a decree “On free cultivators”, according to which the landowner could release the serf for freedom by giving him land. So began the abolition of serfdom in the Baltic states under Alexander 1.

At the same time, Alexander flirted with the nobility, fearing to infringe on her rights. Very strong were the memories of how high-ranking conspiratorial aristocrats dealt with his objectionable father, Paul I. This also fully applied to the Baltic landowners. However, after the uprising of 1802 and the unrest that followed in 1803, the emperor had to pay close attention to the Baltic states.

The consequences of unrest. Decree of Alexander I

After the French Revolution, Russian ruling circles were very afraid of war with France. Concerns worsened when Napoleon came to power. It is clear that in conditions of war no one will want to have a large-scale hotbed of resistance within the country. And given that the Baltic provinces were borderline, the Russian government had double concerns.

In 1803, by order of the emperor, a commission was established which was to develop a plan to improve the life of the Ostsee peasants. The result of their work was the Regulation "On the Livonian Peasants", adopted by Alexander in 1804. Then it was extended to Estonia.

What did the abolition of serfdom in the Baltic states under Alexander 1 (year 1804) provide ? From now on, by law, local peasants were attached to the land, and not as before, to the landowner. Those peasants who owned land allotments became their owners with the right to inherit. Everywhere volost courts were created , composed of three members each. One was appointed by the landowner, one was chosen by the peasant landowners, and another by farm laborers. The court monitored the serviceability of serving the corvee and the rent fee by the peasants, and also, without his decision, the landowner no longer had the right to corporally punish the peasants. This ended well, because the situation increased the size of corvee.

The consequences of agrarian transformations

In fact, the Regulation on the so-called abolition of serfdom in the Baltic States (date - 1804) brought disappointment to all sectors of society. The landlords considered him an encroachment on their primordial rights, laborers, who did not get any benefit from the document, were ready to continue their struggle. 1805 was marked for Estonia by new peasant uprisings. The government again had to resort to troops with artillery. But if the peasants could be dealt with with the help of the army, the emperor could not stop the landowners' discontent.

To appease both those and others, in 1809 the government developed “Additional Articles” to the Regulation. Now the landowners themselves could set the size of the corvee. And they were also given the right to evict any householder from his yard and select peasant land plots. The reason for this could be the assertion that the former owner was negligent in managing his household or simply had a personal need for the landowner.

And in order to prevent subsequent actions of laborers, they reduced the working time in the corvee to 12 hours a day and set the amount of payment for the work done. It became impossible to attract farm laborers to work at night without good reason, and if this happened, then every hour of night work was regarded as an hour and a half day.

Post-war changes in the Baltic states

Even on the eve of the war with Napoleon, the idea of the permissibility of the liberation of peasants from serfdom began to sound more and more often among the Estonian landowners. True, the peasants had to acquire freedom, but leave the land to the landowner. The emperor liked this idea very much. He commissioned the local noble assemblies to develop it. But World War II intervened.

When the hostilities were over, the Estonian noble assembly resumed work on a new bill. By next year, the draft law was completed. According to this document, peasants were given freedom. Absolutely free. But all the land passed into the property of the landowner. In addition, the latter was entrusted with the right to exercise police functions in his lands, i.e. he could easily arrest his former peasants and subject them to corporal punishment.

How did the abolition of serfdom in the Baltic states (1816-1819) occur ? You will learn more about this briefly below. In 1816, the bill was submitted for signature to the tsar, and a royal resolution was received. The law entered into force in 1817 on the lands of the Estland province. The following year, a similar bill began to be discussed by the nobles of Livonia. In 1819, the new law was approved by the emperor. And in 1820, he began to operate in the Livonia province.

The year and date of the abolition of serfdom in the Baltic States is now known to you. But what were the first results? The implementation of the law on the ground was very difficult. Well, who among the peasants will rejoice when they deprive him of land. Fearing mass peasant uprisings, the landowners liberated serfs in parts, and not all at once. Implementation of the bill lasted until 1832. Fearing that landless freed peasants would begin to leave their homes en masse in search of a better life, they were limited in their ability to move. The first three years after gaining freedom, peasants could move only within the borders of their parish, then - the county. And only in 1832 they were allowed to travel throughout the province, and it was not allowed to travel outside it.

The main provisions of the bills on the release of peasants

When the abolition of serfdom in the Baltic states took place, serfs ceased to be considered property, and were declared free people. The peasants lost all rights to the land. Now all the land was declared the property of the landowners. In principle, the peasants recognized the right to buy land and real estate. To exercise this right, already under Nicholas I, the Peasant Bank was established, in which it was possible to take a loan to buy land. However, a small percentage of those released were able to exercise this right.

When serfdom in the Baltic states was abolished, peasants received the right to rent it in return for the lost land. But here everything was left to the landlords. The terms of the land lease were not regulated by law. Most landowners made them simply bonded. And the peasants had no choice but to agree to such a lease. In fact, it turned out that the dependence of the peasants on the landlords remained at the same level.

In addition, no rental terms were initially specified. It turned out that after a year, the land owner could easily conclude a contract for the plot with another peasant. This fact began to impede the development of agriculture in the region. Nobody really tried on the rented land, knowing that tomorrow they could lose it.

Peasants automatically became members of volost communities. . . . , , .

The consequences of the "liberation" of the Baltic peasants

Now you know in what year serfdom was abolished in the Baltic states. But to all of the above, it is worth adding that only the Baltic landowners benefited from the implementation of the law on liberation. And then only for a while. It would seem that the law created the prerequisites for the subsequent development of capitalism: there appeared a lot of free people deprived of the right to the means of production. However, personal freedom turned out to be a simple fiction.

When serfdom was abolished in the Baltic states, peasants could move to the city only with the permission of the landowners. Those, in turn, gave such permissions very rarely. There was no question of any civilian labor. The peasants were forced to work out the same corvée under a contract. And if we add to this the short-term lease agreements, then it becomes clear the decline of peasant farms in the Baltic by the middle of the XIX century.