Apache is a group of culturally related Native American tribes in the southwestern United States, which includes chiricaua, jacarilla, lipan, mescalero, salinero, plains, and western apache. The distant relatives of the Apaches are the Navajos, with whom they share the languages of southern Atabascan.

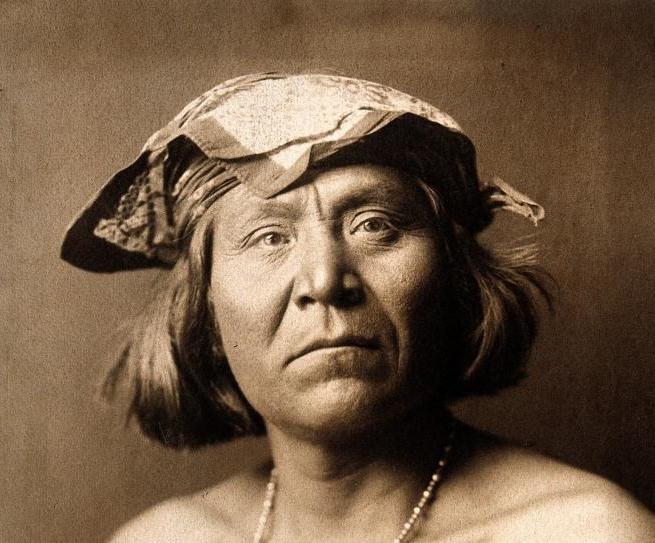

There are Apache communities in Oklahoma, Texas, and reservations in Arizona and New Mexico. Apache people moved throughout the United States and elsewhere, including urban centers. The Apache peoples are politically autonomous, speak several different languages and have different cultures. You can see photos of Apaches in this article.

Habitat

Historically, the Apache homeland has consisted of high mountains, sheltered and flooded valleys, deep canyons, deserts and southern Great Plains, including areas currently located in eastern Arizona, northern Mexico (Sonora and New Mexico, West Texas and South Colorado). These areas are collectively known as Apacheria. The Apache tribes have fought the invading Spanish and Mexican peoples for centuries. The first Apache raids on Sonora apparently took place at the end of the 17th century. The U.S. Army found Apaches to be brutal warriors and skillful strategists.

Name history

People known today as Apaches are the people who first met the conquistadors of the Spanish crown. And so the term "Apache" has its roots in Spanish.

The Spaniards first used the term “Apachu de Nabajo” (Navajo) in the 1620s, referring to people in the Chama region east of the San Juan River. By the 1640s, they applied this term to the South Atabaskan peoples from Cham in the east to San Juan in the west. The ultimate origin is unknown and lost to Spanish history.

Languages

The Apache and Navajo tribal groups in the North American Southwest speak the related languages of the Atabascan language family. Other people speaking them in North America continue to live in Alaska, western Canada, and the northwest Pacific coast. Anthropological evidence suggests that the Apache and Navajo peoples lived in the same northern regions before migrating to the southwest between 1200 and 1500. AD

The nomadic Apache lifestyle complicates accurate dating, primarily because they built less substantial dwellings than other southwestern groups. Since the beginning of the 21st century, significant progress has been made in dating and distinguishing their homes and other forms of material culture. They left behind a more rigorous set of tools and material wealth than other southwestern cultures.

Athabascan languages

The Atabascan-speaking group probably moved to areas that were simultaneously occupied or recently abandoned by other cultures.

Other native speakers of Atabascan, possibly including the southern dialect, have adapted many of the technologies and practices of their neighbors in their cultures. Thus, places where the early southern Atabascans could have lived are hard to find.

And even more difficult to identify as the culture of southern Atabascans. Recent successes have been made in relation to the far southern part of the American southwest.

Apache Story

There are several hypotheses regarding Apache migration. Some claim that they moved southwest of the Great Plains. In the mid-16th century, these mobile groups lived in tents, hunted bison and other wild animals, and used dogs to haul carts loaded with their belongings. A significant number of people and a wide range were recorded by the Spaniards in the 16th century. Apaches are an ancient free nation that has long domesticated dogs.

The Spaniards described the flat dogs as very white, with black spots and "not much more than water spaniels." The flat dogs were slightly smaller than those used to transport goods by modern Inuit and northern indigenous peoples in Canada. Recent experiments show that these dogs could pull loads of up to 50 pounds (20 kg) on long trips at speeds of up to two or three miles per hour (3 to 5 km / h). The theory of migration on the plains connects the Apache people with the culture of the Gloomy River - an archaeological culture known primarily for ceramics and the remains of the house, dated 1675-1725, which were excavated in Nebraska, eastern Colorado and western Kansas.

16th century

In 1540, Coronado reported that the modern territory of the Western Apaches was uninhabited, although some scholars claimed that he simply did not see the American Indians. Other Spanish scholars first mention the Kerejos living west of the Rio Grande in the 1580s. For some historians, this means that the Apaches moved to their current southwestern homeland in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

Other historians note that Coronado reported that Pueblo women and children were often evacuated when his group attacked their homes, and that he saw some homes recently abandoned as he moved up the Rio Grande. This may indicate that the semi-nomadic southern Athabascan warned in advance of their hostile approach and avoided meeting with the Spaniards. Archaeologists find enough evidence of the early presence of the Proto-Apache in the southwestern mountain zone in the 15th century and, possibly, earlier. The presence of Apaches on the plains and in the mountainous southwest indicates that people went through several early migration routes. Apaches are a people perfectly adapted to survival.

Relations with the Spaniards

In general, the recently arrived Spanish colonists who settled in the villages and Apache groups developed a model of interaction over several centuries. Both raided and traded with each other. Period records seem to indicate that relationships depended on certain villages and certain groups that were related to each other. For example, one group may be friends with one village and raid another. When war happens, the Spaniards will send troops; after the battle, both sides would "sign a treaty" and both sides would go home.

Participation in wars

When the United States launched the war against Mexico in 1846, many Apache groups promised American soldiers safe passage through their lands. When the United States seized the former territories of Mexico in 1846, Mangas Coloradas signed a peace treaty with the nation, considering them the conquerors of Mexican land. The uneasy peace between the Indians and the new citizens of the United States lasted until the 1850s. The influx of gold miners into the mountains of Santa Rita led to a conflict with the Apaches. This period is sometimes called the Apache Wars.

Reservations

The reservation concept in the United States was not previously used by the Spanish, Mexicans, or other Apache neighbors. Reservations were often poorly managed, and groups that did not have family relationships were forced to live together. There were no fences to keep people inside or out. The group was often given permission to leave for a short period of time. In other cases, the group left without permission, raided, returned to their homeland to get food or just leave. The military usually had forts nearby. Their job was to keep various groups on reservations, finding and returning those who had left. Reservation policies in the United States created conflict and war with various Apache groups that left reservations for another quarter century.

Deportation

In 1875, the U.S. military forced about 1,500 Apaches Yavapai and Dilzhe'e (better known as Tono Apache) from the Indian Reserve in Rio Verde and several thousand acres of contract land promised to them by the United States government. By order of the Indian Commissioner L.E. Dudley, a U.S. Army man, forced people, young and old, to pass through winter-flooded rivers, mountain passes, and narrow canyon paths.

They were supposed to get to the Indian agency in San Carlos, located 180 miles (290 km). The campaign led to the deaths of several hundred people. People were there in internment for 25 years, while white settlers seized their land. Only a few hundred returned to their lands. On the San Carlos Reservation, Buffalo soldiers from the 9th Cavalry Regiment — replacing the 8th Cavalry Regiment based in Texas — were guarded by the Apaches in 1875-1881.

War for freedom

Beginning in 1879, an Indian uprising against the reservation system led to the “Victorio War” between the group of the notorious leader Victorio and the 9th Cavalry. Victorio made history almost on a par with Apache leader Winnetu.

Most United States stories of this era report that the final defeat of the Apache group occurred when 5,000 American soldiers forced Jeronimo's group of 30-50 men, women and children to surrender on September 4, 1886 in Skeleton Canyon, Arizona.

25 The army sent this group and the Chiricahua scouts, who tracked them down, to the Florida military isolation ward at Fort Pickens, and then to Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

Many books were written on the history of hunting and trapping in the late 19th century. Many of these stories relate to Apache raids and failure of deals with Americans and Mexicans. In the postwar era, the US government organized the removal of Apache children from their families for adoption by white Americans in assimilation programs.