Thermodynamics as an independent branch of physical science arose in the first half of the 19th century. A century of cars struck. The industrial revolution required to study and comprehend the processes associated with the functioning of heat engines. At the dawn of the machine era, single inventors could only afford to use intuition and the “poke method”. There was no public order for discoveries and inventions; no one could even imagine that they could be useful. But when thermal (and a little later electric) machines became the basis of production, the situation changed. Scientists finally gradually sorted out the terminological confusion that reigned until the middle of the XIX century, deciding what to call energy, what force, what - an impulse.

What does thermodynamics postulate

Let's start with well-known information. Classical thermodynamics is based on several postulates (principles), introduced sequentially throughout the XIX century. That is, these provisions are not provable within its framework. They were formulated as a result of a synthesis of empirical data.

The first beginning is the application of the law of conservation of energy to the description of the behavior of macroscopic systems (consisting of a large number of particles). Briefly, it can be formulated as follows: the supply of internal energy of an isolated thermodynamic system always remains constant.

The meaning of the second law of thermodynamics is to determine the direction in which processes occur in such systems.

The third principle makes it possible to precisely determine a quantity such as entropy. Let's consider it in more detail.

The concept of entropy

The formulation of the second law of thermodynamics was proposed in 1850 by Rudolf Clausius: “The spontaneous transfer of heat from a less heated body to a warmer one is impossible”. At the same time, Clausius emphasized the merit of Sadi Carnot, who had already established in 1824 that the proportion of energy that can be turned into a heat engine depends only on the temperature difference between the heater and the refrigerator.

With the further development of the second law of thermodynamics, Clausius introduces the concept of entropy - a measure of the amount of energy that irreversibly transforms into a form unsuitable for conversion to work. Clausius expressed this quantity by the formula dS = dQ / T, where dS, which determines the change in entropy. Here:

dQ is the change in heat;

T is the absolute temperature (the same as that measured in kelvins).

A simple example: touch the hood of your car with the engine running. It is clearly warmer than the environment. But the car’s engine is not designed to heat the hood or water in the radiator. Transforming the chemical energy of gasoline into heat, and then into mechanical, it does useful work - it rotates the shaft. But most of the heat generated is lost, since no useful work can be extracted from it, and what flies out of the exhaust pipe is no longer gasoline. In this case, thermal energy is lost, but does not disappear, but dissipates (dissipates). The hot hood, of course, cools down, and each cycle of the cylinders in the engine again adds warmth to it. Thus, the system seeks to achieve thermodynamic equilibrium.

Entropy Features

Clausius deduced the general principle for the second law of thermodynamics in the formula dS ≥ 0. Its physical meaning can be defined as “non-decreasing” of entropy: in reversible processes it does not change, in irreversible processes it increases.

It should be noted that all real processes are irreversible. The term "non-decreasing" reflects only the fact that a theoretically possible idealized version is also included in the consideration of the phenomenon. That is, the amount of inaccessible energy in any spontaneous process increases.

Ability to achieve absolute zero

Max Planck made a major contribution to the development of thermodynamics. In addition to working on a statistical interpretation of the second law, he took an active part in postulating the third law of thermodynamics. The first wording belongs to Walter Nernst and refers to 1906. Nernst's theorem considers the behavior of an equilibrium system at a temperature tending to absolute zero. The first and second principles of thermodynamics make it impossible to find out what will be the entropy under these conditions.

At T = 0 K, the energy is zero, the particles of the system stop the chaotic thermal movements and form an ordered structure, a crystal with a thermodynamic probability equal to unity. This means that entropy also vanishes (below we will find out why this happens). In reality, she even does this a little earlier, from which it follows that cooling any thermodynamic system, any body to absolute zero is impossible. The temperature will arbitrarily approach this point, but will not reach it.

Perpetuum mobile: impossible, even if you really want to

Clausius generalized and formulated the first and second principles of thermodynamics in this way: the total energy of any closed system always remains constant, and the total entropy increases with time.

The first part of this statement prohibits the perpetual motion machine of the first kind - a device that performs work without the influx of energy from an external source. The second part also prohibits the perpetual motion machine of the second kind. Such a machine would translate the energy of the system into operation without entropy compensation, without violating the conservation law. It would be possible to pump out heat from an equilibrium system, for example, to fry fried eggs or to pour steel due to the energy of thermal motion of water molecules, while cooling it.

The second and third principles of thermodynamics prohibit the perpetual motion machine of the second kind.

Alas, nature can not get anything, not only for nothing, you also have to pay a commission.

Thermal Death

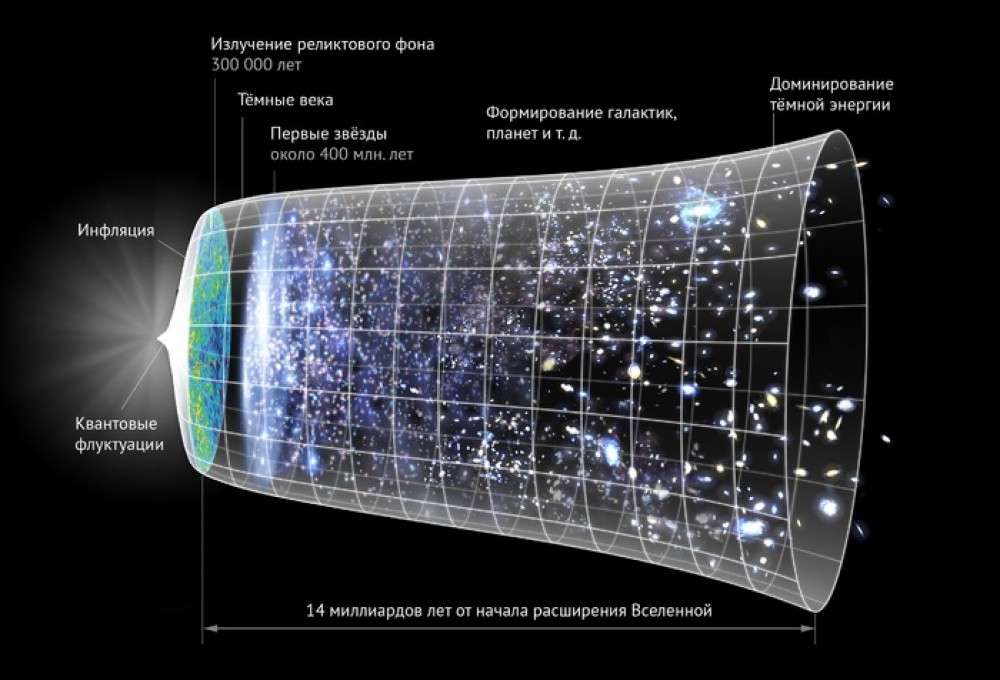

There are few concepts in science that evoked so many ambiguous emotions not only among the general public, but also among the scientists themselves, as much as entropy accounted for. Physicists, and primarily Clausius himself, almost immediately extrapolated the law of non-decreasing first to the Earth, and then to the entire Universe (why not, because it can also be considered a thermodynamic system). As a result, physical quantity, an important element of calculations in many technical applications, began to be perceived as the embodiment of some universal Evil that destroys a bright and good world.

Among scientists, there are also such opinions: since, according to the second law of thermodynamics, entropy is growing irreversibly, sooner or later, all the energy of the Universe will degrade into a diffuse form, and “heat death” will occur. What is there to enjoy? Clausius, for example, did not dare to publish his conclusions for several years. Of course, the “heat death” hypothesis immediately raised many objections. There are serious doubts about its correctness even now.

Daemon sorter

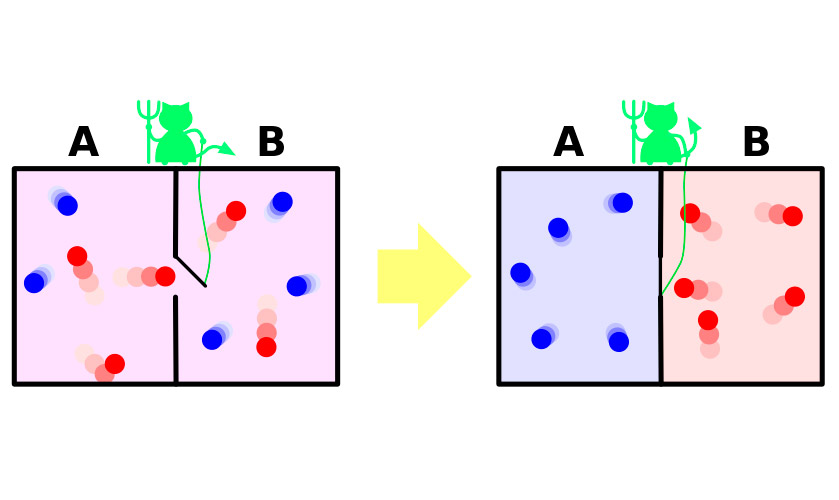

In 1867, James Maxwell, one of the authors of the molecular-kinetic theory of gases, in a very visual (albeit fictional) experiment, demonstrated the apparent paradox of the second law of thermodynamics. Briefly, the experience can be summarized as follows.

Let there be a vessel with gas. The molecules in it move randomly, their speeds are slightly different, but the average kinetic energy is the same throughout the vessel. Now divide the vessel by a partition into two isolated parts. The average velocity of the molecules in both halves of the vessel will remain the same. The partition is guarded by a tiny demon, which allows faster, “hot” molecules to penetrate into one part, and slower “cold" to another. As a result, the gas heats up in the first half, and cools down in the second half, that is, from the state of thermodynamic equilibrium, the system moves to the difference in temperature potentials, which means a decrease in entropy.

The whole problem is that in the experiment the system does not make this transition spontaneously. It receives energy from outside, due to which the partition opens and closes, or the system necessarily includes a demon that spends its energy on the duties of a gatekeeper. An increase in the entropy of the demon will abundantly cover its decrease in the gas.

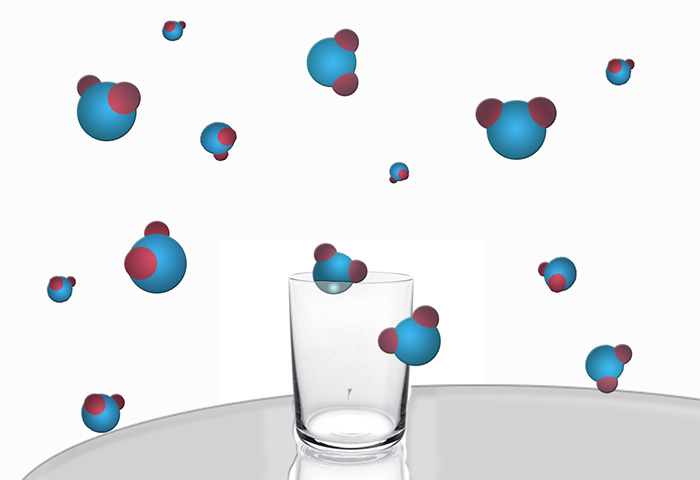

Undisciplined molecules

Take a glass of water and leave it on the table. Watching the glass is not necessary, it is enough to return after a while and check the condition of the water in it. We will see that its quantity has decreased. If you leave the glass for a long time, there will be no water at all in it, since all of it will evaporate. At the very beginning of the process, all water molecules were in a certain region of space bounded by the walls of the glass. At the end of the experiment, they scattered throughout the room. In the volume of a room, molecules have much more opportunities to change their location without any consequences for the state of the system. We will not be able to collect them in a soldered “team” and drive them back into a glass in order to drink water for health reasons.

This means that the system has evolved to a state with higher entropy. Based on the second law of thermodynamics, entropy, or the dispersion of particles in a system (in this case, water molecules) is irreversible. Why is this so?

Clausius did not answer this question, and no one else could do this before Ludwig Boltzmann.

Macro and microstate

In 1872, this scientist introduced into science a statistical interpretation of the second law of thermodynamics. Indeed, macroscopic systems that thermodynamics deals with are formed by a large number of elements whose behavior obeys statistical laws.

Back to the water molecules. Flying randomly around the room, they can occupy different positions, have some differences in speeds (molecules constantly collide with each other and with other particles in the air). Each variant of the state of a system of molecules is called a microstate, and there are a huge number of such variants. When implementing the vast majority of options, the macrostate of the system will not change in any way.

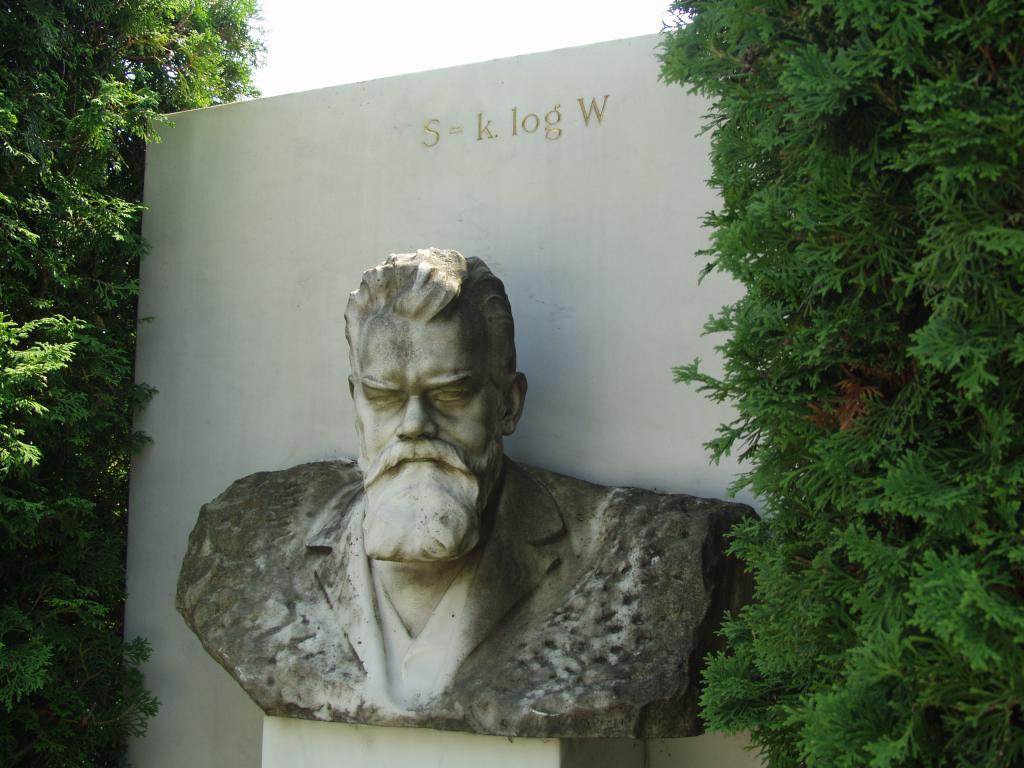

Nothing is forbidden, but something is extremely unlikely

The famous relation S = k lnW connects the number of possible ways in which a certain macrostate of a thermodynamic system (W) can be expressed with its entropy S. The value of W is called the thermodynamic probability. The final form of this formula gave Max Planck. The coefficient k is an extremely small value (1.38 × 10 −23 J / K), characterizing the relationship between energy and temperature, Planck called Boltzmann's constant in honor of the scientist who was the first to propose a statistical interpretation of the second law of thermodynamics.

It is clear that W is always a natural number 1, 2, 3, ... N (there are no fractional number of ways). Then the logarithm of W, and therefore the entropy, cannot be negative. At the only microstate possible for the system, the entropy becomes equal to zero. If we return to our glass, this postulate can be represented as follows: the water molecules randomly scurrying around the room returned to the glass. At the same time, each one exactly repeated its path and took in the glass the same place in which it was before departure. Nothing prohibits the implementation of this option, in which the entropy is zero. Just wait for the implementation of such a vanishingly small probability is not worth it. This is one example of what can only be done theoretically.

Everything mixed up in the house ...

So, molecules randomly fly around the room in different ways. There is no regularity in their location, there is no order in the system, no matter how you change the options for microstates, there is no distinct structure. The glass was the same, but due to the limited space, the molecules did not change their position so actively.

The chaotic, disordered state of the system as the most probable corresponds to its maximum entropy. Water in a glass is an example of a lower entropic state. The transition to it from chaos evenly distributed throughout the room is practically impossible.

Here is an example that is more understandable for all of us - cleaning up a mess in a house. In order to put everything in its place, we also have to expend energy. In the process of this work, it becomes hot for us (that is, we do not freeze). It turns out that entropy can be beneficial. It is so indeed. One can say even more: entropy, and through it the second law of thermodynamics (along with energy) govern the Universe. Take another look at reversible processes. So the world would look if there were no entropy: no development, no galaxies, stars, planets. No life ...

A little more information about "thermal death." There is good news. Since, according to the statistical theory, “forbidden” processes are actually unlikely, fluctuations arise in a thermodynamically equilibrium system - spontaneous violations of the second law of thermodynamics. They can be arbitrarily large. When gravity is included in a thermodynamic system, the distribution of particles will no longer be randomly uniform, and the state of maximum entropy will not be reached. In addition, the Universe is not constant, constant, stationary. Consequently, the very formulation of the issue of "thermal death" is meaningless.