The Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is a formal written decision of the legislature that governs a city, state or country. As a rule, these documents (which, in fact, were three) allow or prohibit something or create a political agenda. Lithuanian statutes are the rules adopted by the legislative bodies of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. By themselves, they differ from case law, which is determined by the courts, and rules issued by state bodies.

In almost all countries, newly adopted laws are published in the government bulletin, which is then distributed in such a way that everyone can become familiar with the statutory law. This is called the statute. Now they play a supporting role among the sources of law, but in the Middle Ages in many states (like Lithuania), statutes essentially replaced a constitution that did not exist at that time.

Legal Issues

The universal problem that lawmakers have faced throughout human history is how to organize published charters. Such publications have the habit of starting small, but they are growing rapidly over time, as new decrees are put into effect taking into account the severity of the moment. In the end, people trying to find a law are forced to sort out a huge number of statutes adopted at various points in time to determine which parts are still valid. Medieval Russian-Lithuanian jurists partially solved this problem by adopting a single Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The essence of the legal act

The decision taken in many countries is to organize the existing law in thematic (“codified”) agreements in publications called codes, and then ensure that new charters are constantly drafted so that they add, change, repeal or move different sections of the code. In turn, theoretically, the code will henceforth reflect the current cumulative state of the statutory law in this jurisdiction. In many countries, any legislative act is subject to constitutional law. However, at a time when it adopted the statute of the Principality of Lithuania, a similar problem did not exist.

The term “statute” is also used to refer to an international treaty established by an institution. A good example would be the Statute of the European Central Bank, as well as, for example, the Statute of the International Court of Justice and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. This document is a partial analogue of the code. This term was adapted in the USA from England in about the 18th century, while on the Russian-Lithuanian (Belarusian) lands it was known since at least the 16th century.

What are the Lithuanian statutes

The legislative act to which this article is devoted consists of three legal codes (1529, 1566 and 1588) written in Ruthenian (Old Russian), translated into Latin, and then into Polish. They formed the basis of the legal system of the Grand Duchy. One of the main sources of the charter was the Old Russian law. The first of these was the Lithuanian Statute of 1529. It is he who is often referred to as the first statute.

First charter

The main purpose of the first Lithuanian statute was to standardize and put together various tribal and city laws in order to codify them as a single document.

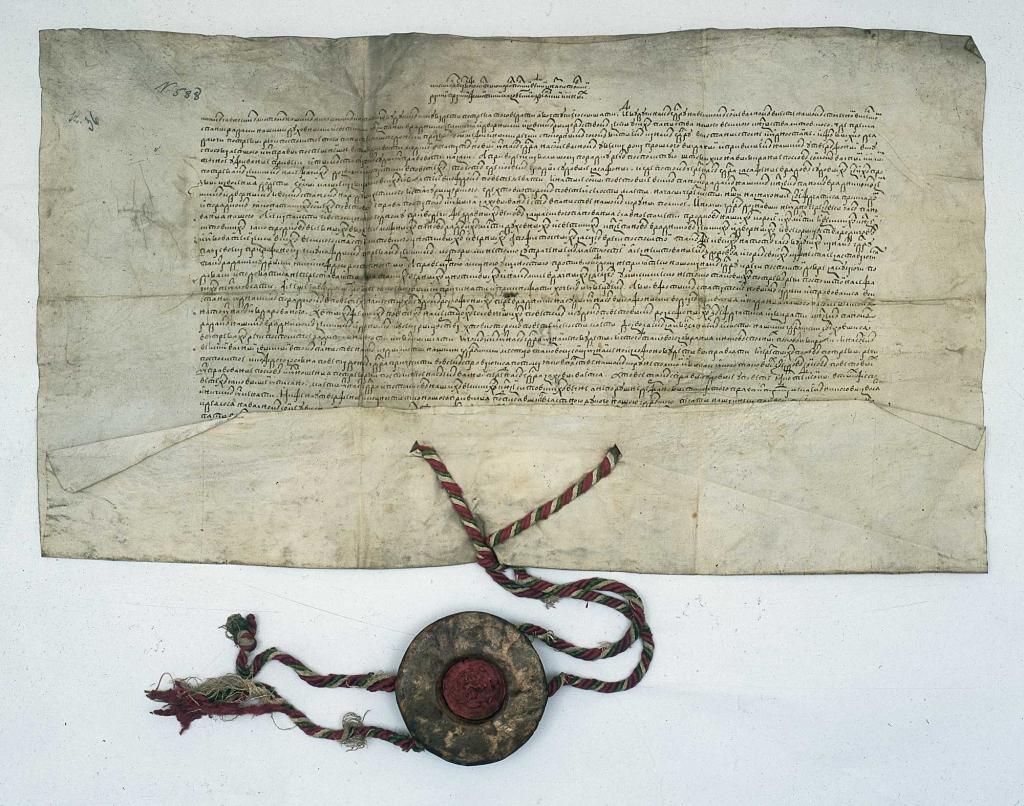

The document was drawn up in 1522 and entered into force in 1529 at the initiative of the Lithuanian Council of Lords. It went down in history under the name "Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania of 1529". It was suggested that codification should be initiated by the Grand Chancellor of Lithuania Nikolai Radziwill as a revision and extension of the Casimir Code. The first edition was revised and supplemented by his successor Albertas Gostautas, who took up the post of Grand Chancellor of Lithuania in 1522.

Second Statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

This law entered into force in 1566 by order of the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund II Augustus and was large and more advanced. The Grand Duke did this because of pressure from the Lithuanian nobility, since the expansion of the rights of the nobles after the publication of the first charter made him redundant. The second law was prepared by a special commission consisting of ten members appointed by the Grand Duke and the Council of Lords.

Third Charter

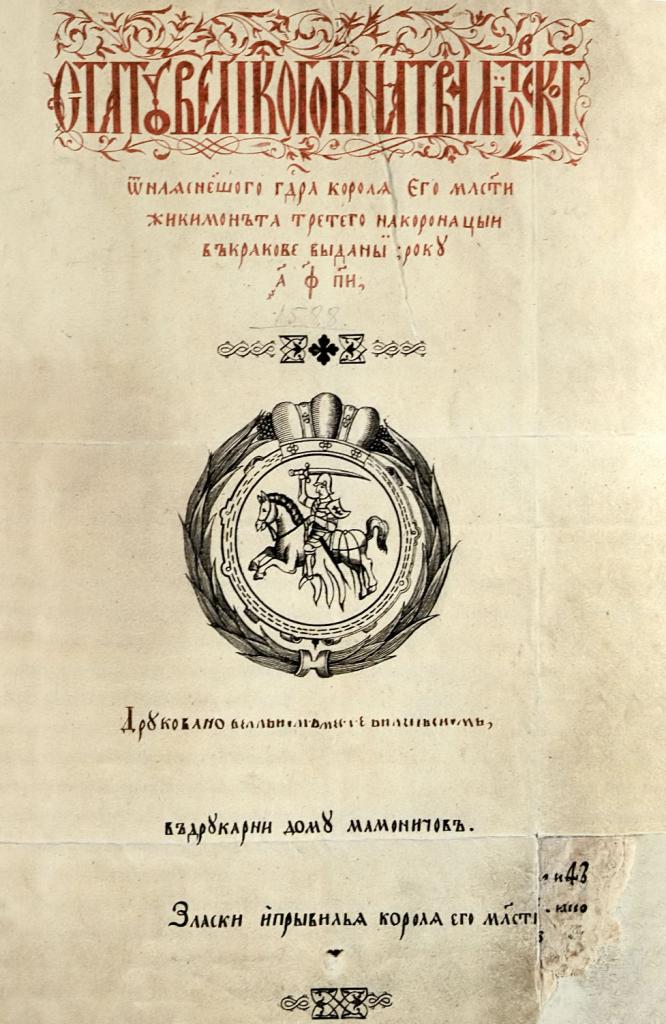

The third of the Lithuanian statutes was adopted in 1588 in response to the Union of Lublin, which created the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The chief author and editor of this charter was the great chancellor of Lithuania, Lev Sapega, who came from Belarusian lands. The Statute was the first to be printed (in contrast to the handwritten laws before it) in Ruthenian, using the Cyrillic alphabet. Translations of the statute were printed in Muscovite Russia, as well as in Poland, where at that time the laws were not fully codified, and consultations were held in the Lithuanian Statute in cases where the relevant Polish laws were unclear or absent.

The charter reorganized and amended existing legislation, as well as introduced new laws. Progressive features included a tendency toward harsh punishments, including the death penalty, which was consistent with the general trend in then-European law. In addition, the charter provides that crimes committed by people from different social strata or against them were punished on the basis of the idea of the equal value of human life. The statutes were supported by the Lithuanian magnates, as they granted them special powers and privileges, allowing them to control the small Lithuanian nobility and peasants. In recognition of his recognition as Grand Duke of Lithuania, Sigismund III Vasa revised the Union of Lublin and approved the third of the Lithuanian statutes.

Features

Many features of the document did not comply with the provisions of the Lublin Union, which was not mentioned at all in the charter. According to the new Lithuanian statute, feudal land tenure on the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was equally valid for both Lithuanian and Polish nobles. This influenced the polonization of the Lithuanian nobility. The text of the Lithuanian statute is kept at the National Historical Museum in Vilnius.

Opposition

The group, which often opposed the statute, came from the Polish nobility, who considered it unlawful, because the Union of Lublin stipulated that no law could be contrary to the law of the union. The document in turn declared laws contrary to the unified law of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Lithuanian statutes were also used in the historically Lithuanian territories annexed by Poland shortly before the signing of the Union of Lublin. These conflicts between statutory schemes in Lithuania and Poland persisted for many years.

The third version of the Statute had many humane features, such as double compensation for killing or harming a woman, a ban on enslaving a free man for any crime, freedom of religion and the recommendation to acquit the accused in the absence of evidence, instead of punishing the innocent. It operated on the territory of Lithuania until 1840, when it was replaced by Russian laws. But until then, many Russian peasants and even nobles (for example, Andrei Kurbsky) fled from despotism to the neighboring Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Copies of charters were usually kept in every county (district), so that they could be used and seen by every person who wanted to do this.

Further conflicts

Attempts by the Lithuanian nobility to limit the power of the Lithuanian magnates led to the “equalizer of rights” movement, culminating in the reforms of the 1697 electoral parliament (May-June), confirmed in the coronation parliament in September 1697 in Porządek sądzenia spraw w Trybunale Wielkiego Księstwa Liteweg. These reforms limited the jurisdiction and competence of several Lithuanian ranks, such as the Hetman, Chancellor, Marshal (Marshal) and Squint (Treasurer), to equate them to the competence of the respective ranks in the Polish crown. Many of these posts were occupied by members of the Sapieha family at that time, and changes were made to reduce the power of this clan. Subsequent reforms also established Polish as an administrative language, replacing Old Russian in written documents and litigation, which contradicts the wording of the Third Statute.

Rating

The statute of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a sign of a progressive European legal tradition and was named a precedent in the Polish and Lithuanian courts. Moreover, he had a great influence on the codification of the Russian legal code of 1649, "Cathedral Code". After the formation of the association with Poland, including both the dynastic union (1385-1569) and the confederate Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569-1795), the Lithuanian Statute was the largest guarantor of the independence of the Grand Duchy.

In 1791, efforts were made to change the system and remove the privileges of the nobility, create a constitutional monarchy with modern civil rights. However, these plans came to naught when Russia, instigated by Austria and Prussia, divided the Commonwealth, although it left the Lithuanian Statute in force in Lithuania until 1840.

Constitution of May 3

The ideas expressed in three statutes influenced the last independent Polish constitution. The document of May 3, 1791 (Polish: Konstytucja 3 Maja, Lithuanian: Gegužės trečiosios konstitucija) was adopted by the Sejm (Parliament) of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a double monarchy consisting of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Drafted over 32 months from October 6, 1788, and formally adopted as government law (Ustawa rządowa), a constitution was created to address the political weaknesses of the Commonwealth. The system of “Golden Freedoms”, also known as “Noble Democracy”, gave disproportionate rights to the nobility (nobility) and over time corrupt politics. The adoption of the Constitution preceded a period of agitation and the gradual implementation of reforms, starting with the Seimas convocation of 1764 and the election of Stanislav Augustus Poniatowski as the last king of the Commonwealth.

Too bold for its time

The constitution sought to supplant the prevailing anarchy, which was supported by some tycoons of a country with a more democratic monarchy. She introduced elements of political equality between the townspeople and the nobility and placed the peasants under the protection of the government, thereby mitigating the worst abuse of serfdom. She banned parliamentary institutions, such as the Libero veto, which made the Diet dependent on any deputy who could unilaterally repeal all legislation adopted by that Diet. Commonwealth neighbors have reacted with hostility to the adoption of the constitution. The Kingdom of Prussia under the leadership of Frederick William II broke its alliance with the Commonwealth, which was attacked and then defeated in the war for the defense of the Constitution through the union of Imperial Russia under the leadership of Catherine the Great and Barsky Confederation - counter-reformist Polish magnates and landless nobles. The king, the main co-author, eventually capitulated to the Confederates.

The end of the Commonwealth

The constitutional legislative procedures of 1791 were formally implemented in accordance with Articles I-XI (and their preamble) in less than 19 months. The legal force of the constitution was confirmed by the content of the Proclamation in 1794 with reference to articles of the Constitution (in particular, article IV). The Proclamation Polyana refers to Tadeusz Kosciuszko. She was released during his rebellion. The Grodno Seimas announced the Constitution of May 3 canceled, but its legal force for this was doubtful on the basis of Article VI of the Constitution of May 3, which allowed its repeal only 25 years after the introduction. The representation of lawyers and historians about the consequences of the entry into force of the Constitution in 1791 regarding its legal force remains unambiguous. By 1795, the existence of a sovereign Polish state ended. Over the next 123 years, the Constitution of May 3, 1791 was seen as evidence of successful internal reform and as a symbol of the possibility of restoring the sovereignty of Poland. The first draft of the Constitution was developed in secret with the participation of several co-authors, including, in particular, King Stanislav Augustus Poniatowski, Stanislav Stasic, Scipio Piatti and probably Julian Ursin Nimchevich. According to two of his main co-authors, Ignatius Potocki and Hugo Kolontage, it was "the last will and testament of the bleeding country." And this testament was written under the inspiration of the Lithuanian statutes.