The formation of a single Russian state is a very long process. Daniil Alexandrovich, the youngest son of Alexander Nevsky, founded the Principality of Moscow, which first collaborated and eventually expelled the Tatars from Russia. Well located in the central river system of Russia and surrounded by protective forests and swamps, Moscow at first was only a vassal of Vladimir, but soon it absorbed its parental state. In this article, through the prism of history, the features of the formation of the Russian united state are considered.

Hegemony of Moscow

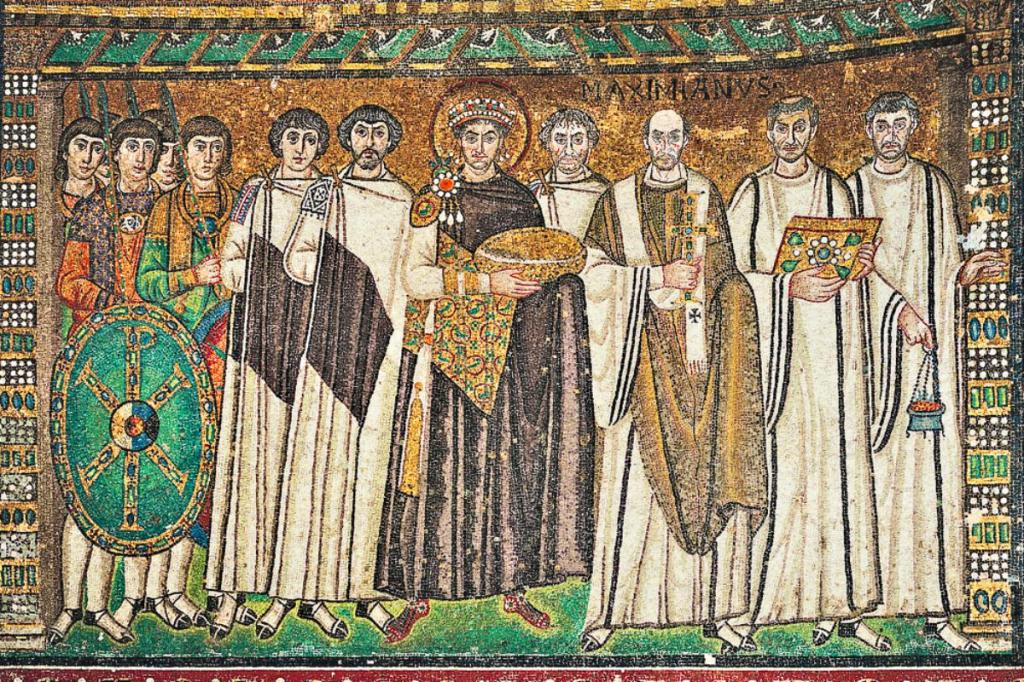

The main factor in the dominance of Moscow was the cooperation of its rulers with the Mongol, who made them agents for collecting Tatar gifts from the Russian principalities. The prestige of the principality was further strengthened when it became the center of the Russian Orthodox Church. Its head, the metropolitan, fled from Kiev to Vladimir in 1299, and a few years later he founded the permanent location of the church in Moscow under the original name of the Kiev metropolitan. At the end of the article, the reader learns about the completion of the formation of a single Russian state.

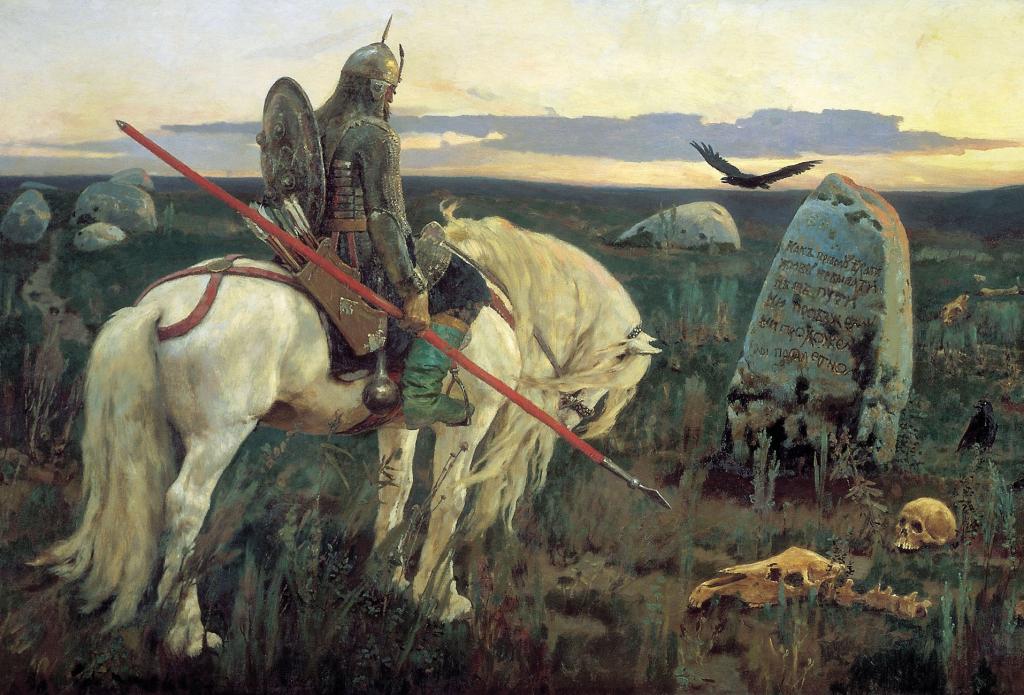

By the middle of the XIV century, the power of the Mongols had weakened, and the great princes felt that they could openly resist the Mongol yoke. In 1380, in Kulikovo on the Don River, the Mongols were defeated, and although this stubborn victory did not put an end to the Tatar rule of Russia, it brought great glory to Grand Duke Dmitry Donskoy. The Moscow administration of Russia was quite firmly founded, and by the middle of the XIV century its territory had expanded significantly due to purchases, war and marriages. This was the main stages in the formation of a single Russian state.

In the XV century, the great Moscow princes continued to consolidate the Russian lands, increasing their population and wealth. The most successful practitioner of this process was Ivan III, who laid the foundations of the Russian national state. Ivan competed with his powerful northwestern adversary, the head of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, for control of some semi-independent Upper principalities in the upper reaches of the Dnieper and Oka rivers.

Further story

Thanks to the retreat of some of the princes, border clashes and a long war with the Novgorod Republic, Ivan III was able to annex Novgorod and Tver. As a result, the Grand Duchy of Moscow tripled under his rule. During his conflict with Pskov, a monk named Filofei wrote a letter to Ivan III with a prophecy that the kingdom of the latter would be the Third Rome. The fall of Constantinople and the death of the last Greek Orthodox emperor contributed to this new idea of Moscow as a New Rome and the residence of Orthodox Christianity.

A contemporary of the Tudors and other new monarchs in Western Europe, Ivan proclaimed his absolute sovereignty over all Russian princes and nobles. Refusing further tribute to the Tatars, Ivan began a series of attacks that paved the way for the complete defeat of the waning Golden Horde, now divided into several khanates and hordes. Ivan and his successors sought to protect the southern borders of their possessions from the attacks of the Crimean Tatars and other hordes. To achieve this, they financed the construction of the Abatis Great Belt and provided estates to the nobles who were required to serve in the army. The estate system served as the basis for the emerging cavalry army.

Consolidation

Thus, internal consolidation was accompanied by the external expansion of the state. By the sixteenth century, the rulers of Moscow considered the entire Russian territory to be their collective property. Various semi-independent princes still demanded certain territories, but Ivan III forced the weaker princes to recognize the Grand Duke of Moscow and his descendants as the undisputed rulers who control military, judicial and foreign affairs. Gradually, the Russian ruler became a powerful autocratic king. The first Russian ruler to officially crown himself "king" was Ivan IV. The formation of a single Russian state is the result of the work of many leaders.

Ivan III tripled the territory of his domination, put an end to the rule of the Golden Horde over Russia, repaired the Moscow Kremlin and laid the foundations of the Russian state. Biographer Fennell concludes that his rule was militarily magnificent and economically sound, and especially points to his territorial annexations and his centralized control over local rulers. But also Fennell, a leading British expert on Ivan III, claims that his rule was also a period of cultural depression and spiritual infertility. Freedom was suppressed on Russian lands. With his fanatical anti-Catholicism, Ivan unveiled the curtain between Russia and the West. For the sake of territorial growth, he stripped his country of the fruits of Western education and civilization.

Further development

The development of tsarist autocratic power reached its peak during the reign of Ivan IV (1547–1584), known as Ivan the Terrible. He strengthened the position of the monarch to an unprecedented degree, since he mercilessly subordinated the nobles to his will, having expelled or executed many by the slightest provocation. Nevertheless, Ivan is often considered a visionary statesman who reformed Russia when he unveiled a new code of laws (Judicial Code of 1550), establishing the first Russian feudal representative body (Zemsky Sobor), which curbed the influence of the clergy and introduced local self-government in the countryside. The formation of a single Russian state is a complex and multifaceted process.

Although his long Livonian war for control of the Baltic coast and access to maritime trade ultimately proved to be a costly failure, Ivan was able to annex the Kazan, Astrakhan and Siberian khanates. These conquests complicated the migration of aggressive nomadic hordes from Asia to Europe through the Volga and the Urals. Thanks to these conquests, Russia acquired a significant Muslim Tatar population and became a multinational and multiconfessional state. Also during this period, the Stroganovs mercantile family settled in the Urals and recruited Russian Cossacks for the colonization of Siberia. These processes proceeded from the fundamental prerequisites for the formation of a single Russian state.

Late period

In the later part of his reign, Ivan divided the kingdom into two parts. In the area known as the oprichnina, Ivan's followers carried out a series of bloody purges of the feudal aristocracy (which he suspected of treason), culminating in the massacre in Novgorod in 1570. This was combined with military losses. Epidemics and crop failures weakened Russia so much that the Crimean Tatars were able to plunder the central regions of Russia and burn Moscow in 1571. In 1572, Ivan refused the oprichnina.

At the end of the reign of Ivan IV, the Polish-Lithuanian and Swedish armies conducted a powerful intervention in Russia, devastating its northern and northwestern regions. The formation of a single Russian state did not end there.

Problem times

The death of the childless son of Ivan Fedor was followed by a period of civil wars and foreign intervention, known as the Time of Troubles (1606–13). The extremely cold summer (1601–1603) destroyed crops, which led to famine in Russia in 1601–1603. and intensified social disorganization. The reign of Boris Godunov ended in chaos, a civil war combined with a foreign invasion, the devastation of many cities and the depopulation of rural areas. The country, shaken by internal chaos, also attracted several waves of interference from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

During the Polish-Moscow war (1605–1618), Polish-Lithuanian troops reached Moscow and established the impostor False Dmitry I in 1605, then supported False Dmitry II in 1607. The decisive moment came when the combined Russian-Swedish army was defeated by Polish troops under the command of the hetman Stanislav Zholkevsky at the Battle of Klushino on July 4, 1610. As a result of the battle, a group of seven Russian nobles overthrew Tsar Vasily Shuisky on July 27, 1610 and recognized the Polish Prince Vladislav IV Tsar of Russia on September 6, 1610. The Poles entered Moscow on September 21, 1610. Moscow revolted, but the riots there were brutally suppressed, and the city was set on fire. The history of the formation of a single Russian state is briefly and clearly described in this article.

The crisis provoked a patriotic national uprising against the invasion in both 1611 and 1612. Finally, an army of volunteers led by merchant Kuzma Minin and Prince Dmitry Pozharsky expelled foreign troops from the capital on November 4, 1612.

Time of Troubles

Russian statehood survived the Time of Troubles and the rule of weak or corrupt tsars thanks to the strength of the central bureaucracy of the government. Officials continued to serve regardless of the legitimacy of the ruler or faction controlling the throne. However, the Time of Troubles, provoked by the dynastic crisis, led to the loss of a significant part of the territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the Russian-Polish war, as well as the Swedish Empire in the war in Ingria.

In February 1613, when the chaos ended and the Poles were expelled from Moscow, the national assembly, consisting of representatives of fifty cities and even some peasants, elected Mikhail Romanov, the youngest son of Patriarch Filaret, to the throne. The Romanov dynasty ruled Russia until 1917.

The immediate task of the new dynasty was to restore peace. Fortunately for Moscow, its main enemies, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden, entered into a fierce conflict with each other, which gave Russia the opportunity to conclude peace with Sweden in 1617 and conclude a truce with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in Lithuania in 1619.

Recovery and return

The restoration of the lost territories began in the middle of the 17th century, when the Khmelnitsky uprising (1648–1657) in Ukraine against Polish rule led to the Pereyaslav Treaty concluded between Russia and the Ukrainian Cossacks. According to the agreement, Russia provided protection to the state of the Cossacks in Left-Bank Ukraine, which was previously under the control of Poland. This provoked a protracted Russo-Polish War (1654-1667), which ended with the Andrusovo Treaty, according to which Poland accepted the loss of the Left-Bank Ukraine, Kiev and Smolensk.

Aggravation of problems

Instead of risking their possessions during the civil war, the boyars collaborated with the first Romanovs, which allowed them to complete the work of bureaucratic centralization. Thus, the state demanded service from both the old and the new nobility, primarily from the military. In turn, the kings allowed the boyars to complete the process of conquering the peasants.

In the previous century, the state gradually limited the rights of peasants to transfer from one landowner to another. Now that the state has completely sanctioned serfdom, the escaped peasants have become fugitives, and the power of the landlords over the peasants tied to their land has become almost complete. Together, the state and the nobles placed a huge tax burden on the peasants, whose rate in the middle of the XVII century was 100 times higher than a hundred years ago. In addition, taxes were imposed on city merchants and artisans from the middle class, and they were forbidden to change their place of residence. All strata of the population levied a military duty and special taxes.

The riots among the peasants and residents of Moscow at that time were endemic. These included the Salty Riot (1648), the Copper Riot (1662), and the Moscow Uprising (1682). Of course, the largest peasant uprising in XVII century Europe broke out in 1667, when the free settlers of southern Russia, the Cossacks, reacted to the growing centralization of the state, the serfs fled from their landowners and joined the rebels. The leader of the Cossacks, Stenka Razin, led his followers up the Volga, fomenting peasant uprisings and replacing local authorities with Cossack rule. The tsarist army finally defeated his troops in 1670. A year later, Stenka was captured and beheaded. However, less than half a century later, the tension of military expeditions led to a new uprising in Astrakhan, which was ultimately suppressed. And so ended the formation of a single centralized Russian state.