China's reforms in the 19th century were the result of a long and extremely painful process. The ideology established over many centuries, which was based on the principle of the deification of the emperor and the superiority of the Chinese over all surrounding peoples, inevitably collapsed, breaking the lifestyle of representatives of all sectors of the population.

New masters of the Celestial Empire

Since China was subjected to the Manchu invasion in the middle of the 17th century, the life of its population has not undergone drastic changes. The overthrown Ming dynasty was replaced by the rulers of the Qing clan, who made Beijing the capital of the state, and all the key posts in the government were taken by the descendants of the conquerors and those who supported them. Otherwise, everything remains the same.

As history has shown, the new masters of the country were zealous stewards, since in the 19th century China entered a fairly developed agrarian country with established domestic trade. In addition, their expansion policy led to the inclusion of 18 provinces in the Middle Kingdom (as its inhabitants called China), and a number of neighboring states paid tribute to it, being in vassal dependence. Every year, Beijing received gold and silver from Vietnam, Korea, Nepal, Burma, as well as the states of Ryukyu, Siam and Sikkim.

Son of Heaven and his subjects

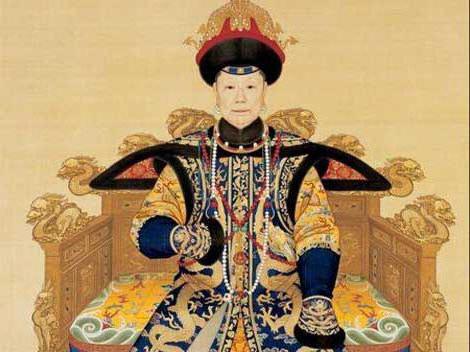

The social structure of China in the 19th century was a kind of pyramid, on top of which sat Bogdykhan (emperor), who enjoyed unlimited power. Below it was a courtyard that consisted entirely of relatives of the overlord. In his direct submission were: the Supreme Chancellery, as well as the state and military councils. Their decisions were implemented by six executive departments, the competence of which included issues: judicial, military, ceremonial, tax and, in addition, related to the appropriation of ranks and the performance of public works.

The domestic policy of China in the 19th century was based on ideology, according to which the emperor (bogdykhan) was the Son of Heaven, who received a mandate from the supreme forces to rule the country. According to this concept, all residents of the country, without exception, were reduced to the level of his children, who were obliged to unquestioningly carry out any command. One involuntarily begs the analogy with the Russian anarchist monarchs of God, whose authority was also given a sacred character. The only difference was that the Chinese considered all foreigners to be barbarians, obliged to tremble before their incomparable Sovereign of the world. In Russia, fortunately, they did not think of this.

Steps of the social ladder

From the history of China in the 19th century, it is known that the dominant position in the country belonged to the descendants of the Manchu conquerors. Below them, on the steps of the hierarchical ladder, were ordinary Chinese (Han), as well as Mongols, who were in the service of the emperor. Next came the barbarians (that is, not the Chinese) who lived in the territory of the Middle Kingdom. These were Kazakhs, Tibetans, Dungans and Uighurs. The lower stage was occupied by the semi-wild tribes of the Juan and Miao. As for the rest of the planet’s population, in accordance with the ideology of the Qing empire, it was regarded as a gathering of external barbarians, unworthy of the attention of the Son of Heaven.

Chinese Army

Since China’s foreign policy in the 19th century focused mainly on the capture and subjugation of neighboring peoples, a significant part of the state budget was spent on maintaining a very large army. It consisted of infantry, cavalry, combat engineer, artillery and navy. The core of the armed forces were the so-called Eight-Banner Forces, formed from the Manchus and Mongols.

Heirs of ancient culture

In the 19th century, Chinese culture was built on a rich heritage inherited from the time of the rulers of the Ming Dynasty and their predecessors. In particular, the ancient tradition was preserved, on the basis of which all applicants for a particular government post were required to pass a rigorous examination of their knowledge. Thanks to this, a layer of highly educated bureaucracy has formed in the country, whose representatives were called "Shenyns."

The representatives of the ruling class were held in constant esteem by the ethical and philosophical teachings of the ancient Chinese sage Kun Fuji (VI-V centuries BC), known today under the name Confucius. Redesigned in the 11th – 12th centuries, it formed the basis of their ideology. The bulk of the population of China in the 19th century professed Buddhism, Taoism, and in the western regions - Islam.

The closure of the political system

Showing a fairly wide religious tolerance, the rulers of the Qing dynasty at the same time made a lot of efforts to preserve the domestic political system. They developed and published a set of laws defining the measure of punishment for political and criminal crimes, and also established a system of mutual responsibility and total surveillance, covering all segments of the population.

At the same time, China in the 19th century was a country closed to foreigners, and especially to those who sought to establish political and economic contacts with his government. Thus, the Europeans' attempts not only to establish diplomatic relations with Beijing, but even to supply goods manufactured by them to its market, ended in failure. The economy of China in the 19th century was so self-sufficient that it allowed to protect it from any influence from the outside.

Uprising at the beginning of the 19th century

However, despite the external well-being, a crisis was gradually brewing in the country, caused by both political and economic reasons. First of all, it was provoked by the extreme uneven economic development of the provinces. In addition, social inequality and infringement of the rights of national minorities were an important factor. Already at the beginning of the 19th century, mass discontent spilled over into popular uprisings led by representatives of the secret societies Heavenly Mind and The Secret Lotus. All of them were brutally crushed by the government.

Defeat in the First Opium War

In its economic development, China in the 19th century lagged significantly behind the leading Western countries, in which this historical period was marked by rapid industrial growth. In 1839, the British government tried to take advantage of this and force to open its markets for its goods. The reason for the outbreak of hostilities, called the “First Opium War” (there were two), was the seizure in the port of Guangzhou of a large consignment of drugs smuggled into the country from British India.

In the course of the fighting, the extreme inability of the Chinese troops to withstand the most advanced army at that time, which Britain possessed, was clearly evident. The subjects of the Son of Heaven suffered one defeat after another, both on land and at sea. As a result, in June 1842, the British met in Shanghai, and after some time forced the Celestial government to sign an act of surrender. According to the agreement, from now on the British were given the right to free trade in five port cities of the country, and the island of Hong Kong (Hong Kong), formerly owned by China, was left to them in “eternal possession”.

The results of the First Opium War, very favorable for the British economy, were disastrous for ordinary Chinese. The flood of European goods drove out products from local manufacturers from the markets, many of which went bankrupt as a result. In addition, China has become a marketplace for a huge amount of drugs. They were imported earlier, but after the opening of the national market for foreign imports, this disaster took on disastrous proportions.

Taiping Rise

The result of increased social tension was another uprising that swept the whole country in the middle of the 19th century. Its leaders called on the people to build a happy future, which they called the "heavenly welfare state." In Chinese, it sounds like Taiping Tiang. Hence the name of the participants in the uprising - the Taipins. Their distinguishing mark was red headbands.

At a certain stage, the rebels managed to achieve significant successes and even create a semblance of a socialist state on the occupied territory. But very soon their leaders were distracted from building a happy life and completely surrendered to the struggle for power. The imperial troops took advantage of this circumstance and, with the help of the British, defeated the rebels.

Second Opium War

As a payment for their services, the British demanded a revision of the trade agreement concluded in 1842 and the provision of large benefits to them. Having been refused, the subjects of the British crown resorted to previously proven tactics and again provoked in one of the port cities. This time, the pretext was the arrest of the Arrow, on board which drugs were also found. The conflict that erupted between the governments of both states led to the outbreak of the Second Opium War.

This time, military operations had even more disastrous consequences for the emperor of the Celestial Empire than those that took place between 1839 and 1842, since the French, who were eager for easy prey, joined the British troops. As a result of joint actions, the Allies occupied a significant part of the territory of the country and again forced the emperor to sign an extremely disadvantageous agreement.

The collapse of the dominant ideology

The defeat in the Second Opium War led to the opening of diplomatic missions of the victorious countries in Beijing, whose citizens received the right to free movement and trade throughout the Celestial Empire. However, the troubles did not end there. In May 1858, the Son of Heaven was forced to recognize the left bank of the Amur as Russian territory, which completely undermined the reputation of the Qing Dynasty in the eyes of his own people.

The crisis caused by the defeat in the Opium Wars and the weakening of the country as a result of popular uprisings led to the collapse of state ideology, which was based on the principle of "China surrounded by barbarians." Those states, which, according to official propaganda, were supposed to "tremble" before the empire headed by the Son of Heaven, turned out to be much stronger than it. In addition, foreigners who freely visited China told its residents about a completely different world order, which is based on principles that exclude the worship of a deified ruler.

Forced Reforms

It was very pitiable for the leadership of the country and things related to finance. Most provinces, which were formerly Chinese tributaries, came under the protectorate of more powerful European states and stopped replenishing the imperial treasury. Moreover, at the end of the 19th century, China fell into rebellion, as a result of which considerable damage was caused to European entrepreneurs who opened their enterprises on its territory. After their suppression, the heads of eight states demanded large amounts of compensation to the affected owners as compensation.

The government, led by the imperial Qing dynasty, was on the verge of collapse, prompting him to take the most urgent measures. They became the reforms, long overdue, but implemented only in the period of the 70–80s. They led to the modernization of not only the economic structure of the state, but also to a change in both the political system and the entire prevailing ideology.