Who created the first transistor? This question worries a lot of people. The first patent for the field-effect transistor principle was filed in Canada by the Austro-Hungarian physicist Julius Edgar Lilienfeld on October 22, 1925, but Lilienfeld did not publish any scientific articles about his devices, and his work was ignored by industry. Thus, the world's first transistor has sunk into history. In 1934, the German physicist Dr. Oscar Heil patented another field effect transistor. There is no direct evidence that these devices were built, but later work in the 1990s showed that one of Lilienfeld's projects worked as described and yielded significant results. It is now a well-known and generally accepted fact that William Shockley and his assistant Gerald Pearson created working versions of the apparatus from Lilienfeld's patents, which, of course, were never mentioned in any of his later scientific works or historical articles. The first transistor computers, of course, were built much later.

Bella Lab

Bell's lab worked on a transistor built to produce extremely pure germanium “crystal” diode mixers, used in radar installations as an element of a frequency mixer. In parallel with this project, there were many others, including a transistor with germanium diodes. Early tube-based circuits did not have a fast switching function, and instead, the Bell team used solid-state diodes. The first transistor computers worked on a similar principle.

Further research by Shockley

After the war, Shockley decided to try to build a triode-like semiconductor device. He secured funding and laboratory space, and then began to deal with the problem with Bardin and Bratten. John Bardin eventually developed a new branch of quantum mechanics, known as surface physics, to explain his first failures, and these scientists eventually managed to create a working device.

The key to the development of the transistor was a further understanding of the process of electron mobility in a semiconductor. It was proved that if there was some way to control the electron flow from the emitter to the collector of this newly discovered diode (discovered in 1874, patented in 1906), an amplifier could be built. For example, if you place contacts on either side of the same type of crystal, the current will not pass through it.

In fact, it turned out to be very difficult. The crystal size would have to be more averaged, and the number of supposed electrons (or holes) that needed to be "injected" was very large, which would make it less useful than an amplifier, because it would require a large injection current. Nevertheless, the whole idea of a crystalline diode was that the crystal itself could hold electrons at a very small distance, while being practically on the verge of depletion. Apparently, the key was to make the input and output contacts very close to each other on the crystal surface.

Bratten's writings

Bratten began to work on creating such a device, and hints of success still continued to appear when the team worked on the problem. Invention is hard work. Sometimes the system works, but then another failure occurs. Sometimes the results of Bratten's work began to work unexpectedly in water, apparently because of its high conductivity. Electrons in any part of the crystal migrate due to close charges. Electrons in emitters or "holes" in the collectors accumulated directly on top of the crystal, where they receive the opposite charge, "floating" in air (or water). However, they could be pushed off the surface using a small amount of charge from any other place on the crystal. Instead of requiring a large supply of injected electrons, a very small number in the right place on the crystal will do the same.

The new experience of the researchers to some extent helped to solve the previously arisen problem of a small control area. Instead of having to use two separate semiconductors connected by a common but tiny area, one large surface will be used. The outputs of the emitter and collector would be located on top, and the control wire is placed on the base of the crystal. When a current was applied to the "base" terminal, the electrons would be pushed out through the semiconductor block and collected on the far surface. While the emitter and collector were very close together, this would have to provide enough electrons or holes between them to start conducting.

Joining Bray

An early witness to this phenomenon was Ralph Bray, a young graduate student. He joined the development of a germanium transistor at Purdue University in November 1943 and received the difficult task of measuring the scattering resistance at a metal-semiconductor contact. Bray discovered many anomalies, such as high-resistance internal barriers in some germanium samples. The most curious phenomenon was the exceptionally low resistance observed with voltage pulses. The first Soviet transistors were developed based on these American developments.

Breakthrough

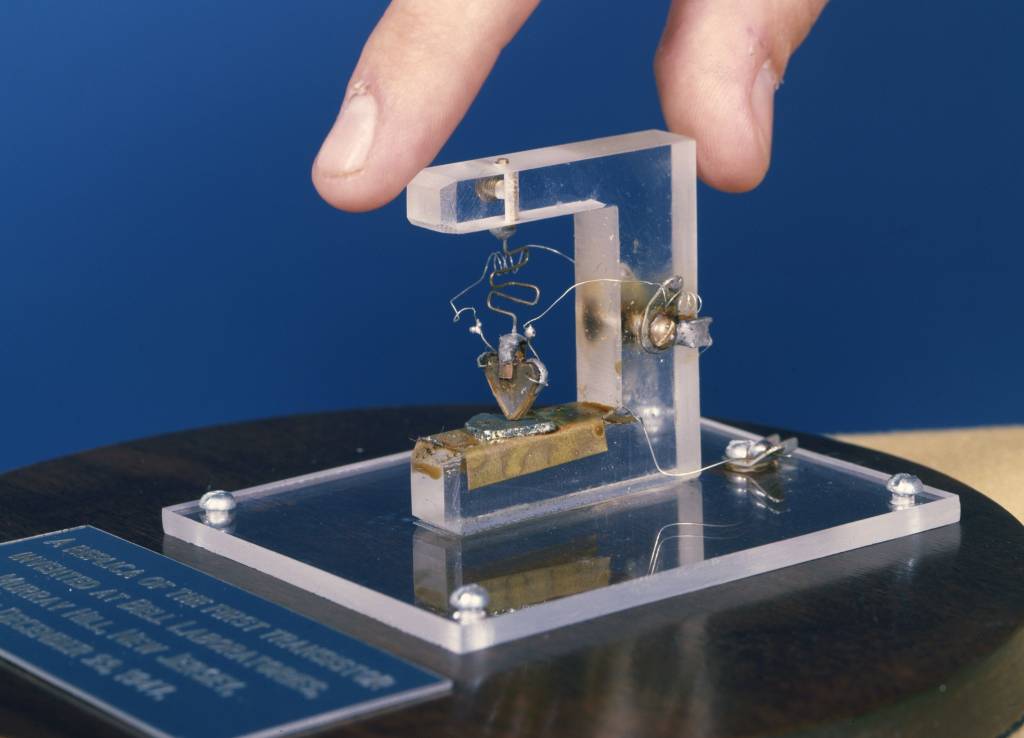

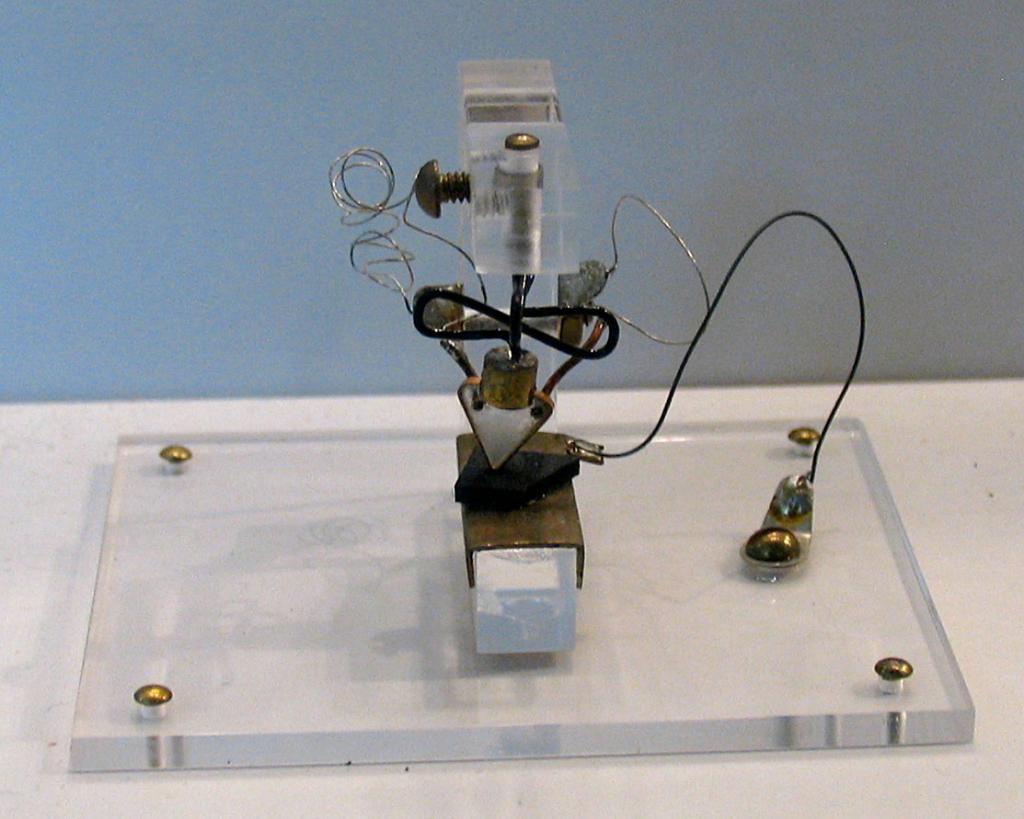

On December 16, 1947, using a point-to-point contact, contact was made with a germanium surface anodized to ninety volts, the electrolyte was washed off in H 2 O, and then several gold spots fell on it. Gold contacts were pressed to bare surfaces. The separation between the points was about 4 × 10 -3 cm. One point was used as a grid, and the other point was used as a plate. The grid evasion (DC) should have been positive in order to gain voltage power gain at a plate offset of about fifteen volts.

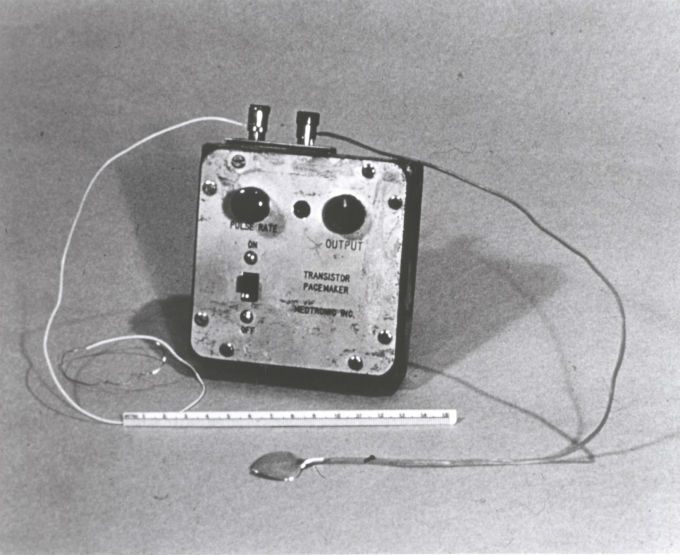

The invention of the first transistor

A lot of questions are connected with the history of this miracle mechanism. Some of them are familiar to the reader. For example: why were the first transistors of the USSR PNP-type? The answer to this question lies in the continuation of this whole story. Bratten and H.R. Moore demonstrated to several colleagues and managers at Bell Labs the afternoon of December 23, 1947, the result they achieved, because this day is often referred to as the birth date of the transistor. The PNP-pin germanium transistor worked as a speech amplifier with a power gain of 18. This is the answer to the question why the first transistors of the USSR were PNP-type, because they were purchased from the Americans. In 1956, John Bardin, Walter Hauser Bratten, and William Bradford Shockley were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their study of semiconductors and the discovery of the transistor effect.

Twelve people are referred to as directly involved in the invention of the transistor in the Bell lab.

The very first transistors in Europe

At the same time, some European scientists fired up the idea of solid-state amplifiers. In August 1948, German physicists Herbert F. Mathart and Heinrich Welcker, who worked at the Compagnie des Freins et Signaux Westinghouse Institute in Aulnay-sous-Bois, France, filed a patent application for an amplifier based on a minority that they called a “transistor”. Since Bell Labs did not publish the transistor until June 1948, the transistor was considered independently designed. For the first time, Mataré observed the effects of steepness in the manufacture of silicon diodes for German radar equipment during World War II. Transistors were commercially manufactured for the French telephone company and the military, and in 1953, a solid-state radio with four transistors was demonstrated at a radio station in Dusseldorf.

Bell Telephone Laboratories needed a name for a new invention: Semiconductor Triode, Tried States Triode, Crystal Triode, Solid Triode and Iotatron were reviewed, but the “transistor" invented by John R. Pierce was a clear winner in the domestic vote (partly due to the proximity that engineers Bella was developed for the suffix "-histor").

The first commercial transistor production line in the world was at Western Electric's Union Boulevard plant in Allentown, PA. Production began on October 1, 1951 with a point contact germanium transistor.

Further application

Until the early 1950s, this transistor was used in all types of production, but there were still significant problems that prevented its wider use, such as moisture sensitivity and the fragility of wires attached to germanium crystals.

Shockley was often accused of plagiarism due to the fact that his work was very close to the work of the great, but unrecognized Hungarian engineer. But Bell Labs' attorneys quickly settled this issue.

Nevertheless, Shockley was outraged by the attacks from critics and decided to demonstrate who was the real brain of the great epic of the invention of the transistor. Just a few months later, he invented a completely new type of transistor with a very peculiar “sandwich structure”. This new form was much more reliable than the fragile point contact system, and as a result, it was precisely it that began to be used in all transistors of the 60s of the XX century. Soon, it developed into a bipolar junction apparatus, which became the basis for the first bipolar transistor.

The static induction device, the first high-frequency transistor concept, was invented by Japanese engineers Jun-ichi Nishizawa and Y. Watanabe in 1950 and finally was able to create experimental prototypes in 1975. It was the fastest transistor in the 80s of the twentieth century.

Further developments included devices with an expanded connection, a surface-barrier transistor, diffusion, tetrode and pentode. A silicon diffusion mesa transistor was developed in 1955 at Bell and is commercially available from Fairchild Semiconductor in 1958. Space was a type of transistor developed in the 1950s as an improvement over a point contact transistor and a later alloy transistor.

In 1953, Filko developed the world's first high-frequency surface-barrier device, which was also the first transistor suitable for high-speed computers. The world's first transistor car radio, manufactured by Philco in 1955, used surface-barrier transistors in its circuit.

Problem solving and refinement

With the solution of the problems of fragility, the problem of cleanliness remained. Creating germanium of the required purity turned out to be a serious problem and limited the number of transistors that actually worked from this batch of material. Temperature sensitivity of germanium also limited its usefulness.

Scientists have suggested that silicon will be easier to manufacture, but few have explored this possibility. Morris Tanenbaum at Bell Laboratories was the first to develop a working silicon transistor on January 26, 1954. A few months later, Gordon Thiel, who works independently at Texas Instruments, developed a similar device. Both of these devices were made by controlling the doping of single silicon crystals when they were grown from molten silicon. A higher method was developed by Morris Tanenbaum and Calvin S. Fuller at Bell Laboratories in early 1955 by gas diffusion of donor and acceptor impurities into single-crystal silicon crystals.

Field effect transistors

The field effect transistor was first patented by Julis Edgar Lilienfeld in 1926 and Oscar Hale in 1934, but practical semiconductor devices (field effect transistors [JFET]) were developed later after the effect of the transistor was observed and explained by the team of William Shockley at Bell Labs in 1947, immediately after the expiration of the twenty-year patent period.

The first type of JFET was a static induction transistor (SIT), invented by Japanese engineers Jun-ichi Nishizawa and Y. Watanabe in 1950. SIT is a JFET type with a short channel length. A semiconductor field effect transistor (MOSFET) made of metal-oxide-semiconductor, which largely supplanted the JFET and had a profound influence on the development of electronic electronics, was invented by Down Kahng and Martin Atalla in 1959.

Field effect transistors can be devices with a majority charge, in which the current is transported mainly by majority carriers or devices with carriers of lower charges, in which the current is mainly due to the flow of minority carriers. The device consists of an active channel through which charge carriers, electrons or holes enter the sewer from the source. The terminal leads of the source and drain are connected to the semiconductor through ohmic contacts. Channel conductivity is a function of the potential applied through the gate and source terminals. This principle of operation gave rise to the first all-wave transistors.

All field effect transistors have source, drain, and gate terminals that roughly correspond to the emitter, collector, and BJT base. Most field effect transistors have a fourth terminal, called a chassis, base, mass, or substrate. This fourth terminal serves to bias the transistor into operation. It is rarely necessary to make non-trivial use of case terminals in circuits, but its presence is important when setting up the physical layout of an integrated circuit. The gate size, length L in the diagram, is the distance between the source and the drain. Width is the expansion of the transistor in the direction perpendicular to the cross section in the diagram (i.e., to / from the screen). Usually the width is much larger than the length of the gate. A shutter length of 1 μm limits the upper frequency to about 5 GHz, from 0.2 to 30 GHz.