The expression "velvet revolution" appeared in the late 1980s - early 1990s. It does not fully reflect the nature of the events described in the social sciences by the term “revolution”. This term always means qualitative, radical, profound changes in the social, economic and political spheres that lead to the transformation of all social life, a change in the model of society.

What it is?

The Velvet Revolution is the general name for the processes that took place in Central and Eastern Europe from the late 1980s to the early 1990s. The collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 became their original symbol.

The name “velvet revolution” was given to these political coups because in most states they were carried out bloodlessly (except Romania, where there was an armed uprising and unauthorized reprisal against N. Ceausescu, the former dictator, and his wife). Events everywhere except Yugoslavia occurred relatively quickly, almost instantly. At first glance, the similarity of their scenarios and coincidence in time is surprising. However, let's look at the causes and essence of these upheavals - and we will see that these coincidences are not accidental. This article will give a definition of the term "velvet revolution" briefly and help to understand its causes.

The events and processes that took place in Eastern Europe in the late 80s and early 90s are of interest to politicians, scientists, and the general public. What are the causes of the revolution? And what is their essence? Let's try to answer these questions. The first in a whole series of similar political events in Europe was the "velvet revolution" in Czechoslovakia. We’ll start with her.

Events in Czechoslovakia

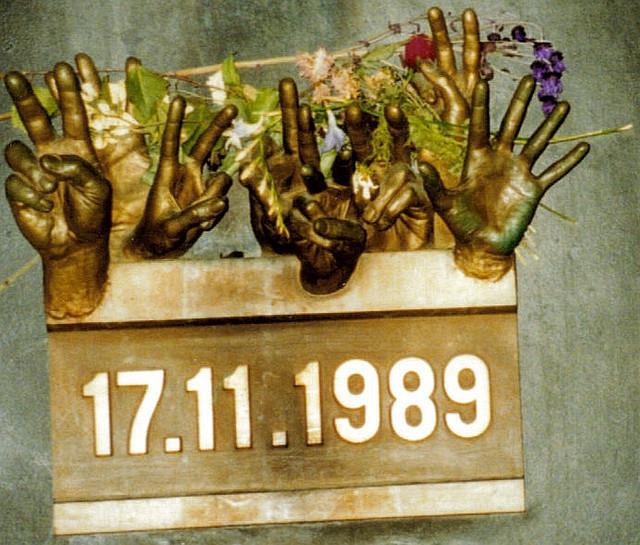

In November 1989, fundamental changes took place in Czechoslovakia. The Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia led to a bloodless overthrow of the communist system as a result of protests. The decisive impulse was a student demonstration organized on November 17 in memory of Jan Opletal, a student from the Czech Republic who died during protests against the Nazi occupation of the state. As a result of the events of November 17, more than 500 people were injured.

On November 20, students went on strike, and mass demonstrations began in many cities. On November 24, the first secretary and several other leaders of the country's Communist Party resigned. On November 26, a grand rally was held in the center of Prague, about 700 thousand people became participants in it. On November 29, parliament canceled the constitutional article on the leadership of the Communist Party. On December 29, 1989, Alexander Dubcek was elected chairman of the parliament, and Vaclav Havel was elected president of Czechoslovakia. The reasons for the "velvet revolution" in Czechoslovakia and other countries will be described below. We will also get acquainted with the opinions of reputable experts.

Reasons for the Velvet Revolution

What are the reasons for such a radical breakdown of the social system? A number of scientists (for example, V.K. Volkov) see the internal objective causes of the 1989 revolution in the gap between the productive forces and the nature of production relations. Totalitarian or authoritarian-bureaucratic regimes became an obstacle to the scientific, technical and economic progress of countries, slowed down the integration process even within the CMEA. Almost half a century of experience in the countries of Southeast and Central Europe has shown that they are far behind the advanced capitalist states, even those with whom they were once on the same level. For Czechoslovakia and Hungary, this is a comparison with Austria, for the GDR - with the Federal Republic of Germany, for Bulgaria - with Greece. The GDR, leading in the CMEA, according to the UN, in 1987 in terms of GP per capita occupied only 17th place in the world, Czechoslovakia - 25th place, USSR - 30th. The gap was widening in the standard of living, the quality of medical services, social security, culture and education.

The lag of the countries of Eastern Europe began to take on a stadia character. A control system with centralized strict planning, as well as super-monopoly, the so-called command-administrative system generated production inefficiency, its decay. This became especially noticeable in the 50-80s, when a new stage of scientific and technological progress was delayed in these countries, which brought Western Europe and the United States to a new, "post-industrial" level of development. Gradually, towards the end of the 70s, a tendency began to turn the socialist world into a secondary socio-political and economic force on the world stage. Only in the military-strategic field did he retain strong positions, and even that was mainly due to the military potential of the USSR.

National factor

Another powerful factor due to which the “velvet revolution” of 1989 came about was the national one. As a rule, national pride was prejudiced by the fact that the authoritarian-bureaucratic regime resembled the Soviet one. The tactless actions of the Soviet leadership and representatives of the USSR in these countries, their political mistakes acted in the same direction. A similar thing was observed in 1948, after the breakdown of relations between the USSR and Yugoslavia (which later led to the “velvet revolution” in Yugoslavia), during trials modeled on Moscow’s pre-war leaders, etc. The leadership of the ruling parties, in turn, adopting dogmatic experience The USSR contributed to the change of local regimes according to the Soviet type. All this gave rise to the feeling that such a system was imposed from the outside. This was facilitated by the intervention of the leadership of the USSR in the events taking place in Hungary in 1956 and in Czechoslovakia in 1968 (later the "velvet revolution" in Hungary and Czechoslovakia took place). The idea of "Brezhnev’s doctrine," that is, limited sovereignty, was entrenched in the minds of people. The majority of the population, comparing the economic situation of their country with the situation of neighbors in the West, began to involuntarily link political and economic problems together. Infringement of national feelings, socio-political dissatisfaction exerted their influence in one direction. As a result, crises began. June 17, 1953 the crisis occurred in the GDR, in 1956 in Hungary, in 1968 in Czechoslovakia, and in Poland it occurred repeatedly in the 60s, 70s and 80s. They, however, did not have a positive authorization. These crises only contributed to the discrediting of existing regimes, the accumulation of so-called ideological shifts that usually precede political changes, and the creation of a negative assessment of parties in power.

The influence of the USSR

At the same time, they showed why the authoritarian-bureaucratic regimes were stable - they belonged to the OVD, the "socialist community", were under pressure from the leadership of the USSR. Any criticism of the existing reality, any attempts to make corrections to the theory of Marxism from the standpoint of creative understanding, taking into account the existing reality, were declared "revisionism", "ideological sabotage", etc. The lack of pluralism in the spiritual sphere, uniformity in culture and ideology led to double-mindedness, political passivity of the population, conformism, which corrupted the personality morally. Of course, progressive intellectual and creative forces could not accept this.

Political party weakness

Increasingly, revolutionary situations began to arise in the countries of Eastern Europe. Watching how perestroika was taking place in the USSR, the population of these countries expected similar reforms in their homeland. However, at the decisive moment, the weakness of the subjective factor revealed itself, namely the lack of mature political parties that could bring about serious changes. The ruling parties for a long time of their uncontrolled reign have lost their creative streak and ability to renew. Their political character was lost, which became just a continuation of the state bureaucratic machine, and more and more lost contact with the people. These parties did not trust the intelligentsia, the youth did not pay enough attention, could not find a common language with her. Their policy lost the confidence of the population, especially after the leadership was corroded more and more by corruption, personal enrichment began to flourish, moral guidelines were lost. It is worth noting the repression against the discontented, "dissidents" that were practiced in Bulgaria, Romania, East Germany and other countries.

The ruling parties, which seemed powerful and monopolistic, separated from the state apparatus and gradually began to fall apart. Disputes that began about the past (the opposition considered the communist parties responsible for the crisis), the struggle between the "reformers" and the "conservatives" inside them - all this paralyzed the activities of these parties to a certain extent, and they gradually lost their combat effectiveness. And even in such conditions, when the political struggle intensified, they still hoped that they had a monopoly on power, but they miscalculated.

Was it possible to avoid these events?

Is a "velvet revolution" inevitable? It was hardly possible to avoid it. This is primarily due to internal causes, which we have already mentioned. What happened in Eastern Europe is largely the result of an imposed model of socialism, a lack of freedom for development.

The perestroika that began in the USSR seemed to give an impetus to socialist renewal. But many leaders of the countries of Eastern Europe could not understand the urgent need for a radical reorganization of the whole society, were unable to receive the signals sent by time itself. Accustomed only to receive instructions from above, the party masses turned out to be disoriented in this situation.

Why did the leadership of the USSR not intervene?

But why did the Soviet leadership, who had anticipated imminent changes in the countries of Eastern Europe, not intervened in the situation and removed the former leaders from power, their conservative actions only reinforcing the discontent of the population?

Firstly, there could be no talk of forceful pressure on these states after the events of April 1985, the withdrawal of the Soviet Army from Afghanistan and the declaration of freedom of choice. This was clear to the opposition and the leadership of Eastern Europe. This circumstance disappointed some, it inspired others.

Secondly, at multilateral and bilateral negotiations and meetings between 1986 and 1989, the leadership of the USSR repeatedly declared the perniciousness of stagnation. But how did they react to this? Most of the heads of state in their actions did not show a desire for change, preferring to implement only the very minimum of necessary changes, which did not affect the whole mechanism of the power system that has developed in these countries. So, only in words did the BKP leadership welcome the perestroika in the USSR, trying to maintain the current regime of personal power with the help of many shocks in the country. The heads of the CPC (M. Jakesh) and the SED (E. Honecker) resisted the changes, trying to limit them to hopes that the alleged restructuring in the USSR was doomed to fail, the influence of the Soviet example. They still hoped that while maintaining a relatively good standard of living, serious reforms could still be dispensed with.

First, in a narrow composition, and then with the participation of all representatives of the SED Politburo on October 7, 1989, in response to the arguments given by M. S. Gorbachev that it was urgent to take the initiative into their own hands, the head of the GDR said that it was not worth teaching them live when in the shops of the USSR "there is not even salt." The people that evening went out into the street, initiating the collapse of the GDR. N. Ceausescu in Romania stained himself with blood, betting on repression. And where the reforms passed with the preservation of the previous structures and did not lead to pluralism, real democracy and the market, they only contributed to uncontrolled processes and decomposition.

It became clear that without the military intervention of the USSR, without its safety net on the side of the existing regimes, their margin of stability was actually small. It is also necessary to take into account the psychological mood of citizens, who played a big role, because people wanted change.

Western countries, in addition, were interested in the fact that opposition forces came to power. They supported these forces in the election campaigns financially.

The result was the same in all countries: during the transfer of power on a contractual basis (in Poland), exhaustion of trust in the reform programs of the HRWP (in Hungary), strikes and mass demonstrations (in most countries), or uprisings ("velvet revolution" in Romania) power passed into the hands of new political parties and forces. This was the end of an era. So the "velvet revolution" took place in these countries.

The essence of the change

On this issue, Yu. K. Knyazev points out three points of view.

- First one. In four states (the "velvet revolution" in the German Democratic Republic, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Romania), at the end of 1989, people's democratic revolutions took place, thanks to which a new political course began to take place. The revolutionary changes of 1989-1990 in Poland, Hungary and Yugoslavia were a quick end to evolutionary processes. Similar shifts since the end of 1990 began to occur in Albania.

- The second one. The "velvet revolutions" in Eastern Europe are just the apical coups, thanks to which alternative forces came to power, who did not have a clear program of social reorganization, and therefore they were doomed to defeat and soon to leave the political arena of the countries.

- The third. These events were counter-revolutions, not revolutions, since they had an anti-communist character, they were aimed at removing the ruling workers and communist parties from power and not supporting the socialist choice.

General direction of movement

The general direction of movements, however, was one-sided, despite the diversity and specificity in different countries. These were speeches against totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, gross violations of the freedoms and rights of citizens, against social injustice in society, corruption of power structures, illegal privileges and low living standards of the population.

They were a rejection of the one-party state administrative command system, which plunged all the countries of Eastern Europe into deep crises and failed to find a worthy exit from the created situation. In other words, we are talking about democratic revolutions, and not about apical coups. This is evidenced not only by numerous rallies and demonstrations, but also by the results of the general elections subsequently held in each country.

The Velvet Revolutions in Eastern Europe were not only against, but also for. For the establishment of true freedom and democracy, social justice, political pluralism, improvement of the spiritual and material life of the population, recognition of universal values, an effective economy developing according to the laws of a civilized society.

Velvet Revolutions in Europe: The Results of Transformations

The countries of CEE (Central and Eastern Europe) are beginning to develop along the path of creating legal democratic states, a multi-party system, and political pluralism. The transfer of power to government from the hands of the party apparatus was carried out. The new government bodies acted on a functional rather than sectoral basis. A balance is maintained between different branches, the principle of separation of powers.

In CEE, the parliamentary system has finally stabilized. None of them established a strong president’s power, and a presidential republic did not arise. The political elite felt that after a totalitarian period, such power could slow down the democratic process. V. Havel in Czechoslovakia, L. Walesa in Poland, J. Zhelev in Bulgaria tried to strengthen the presidential power, but public opinion and parliaments opposed this. The president did not define economic policy anywhere and did not take responsibility for its implementation, that is, he was not the head of the executive branch.

The fullness of power lies with the parliament, executive power belongs to the government. The composition of the latter is approved by the parliament and monitors its activities, adopts the state budget and the law. Free presidential and parliamentary elections have become a manifestation of democracy.

What forces came to power?

In almost all the countries of CEE (except the Czech Republic), power passed painlessly from one hand to another. In Poland, this happened in 1993, the "velvet revolution" in Bulgaria caused the transfer of power in 1994, and in Romania in 1996.

In Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary left-wing forces came to power, in Romania - right-wing forces. Shortly after the “velvet revolution” was launched in Poland, the Union of Left Centrist Forces won the parliamentary elections in 1993, and in 1995 A. Kwasniewski, its leader, won the presidential election. In June 1994, the Hungarian Socialist Party won the parliamentary elections, D. Horn, its leader, led the new social liberal government. At the end of 1994, the socialists of Bulgaria won 125 out of 240 seats in parliament as a result of elections.

In November 1996, in Romania, power passed to the center-right. E. Konstantinescu became president. In 1992-1996, the Democratic Party had power in Albania.

Political environment by the end of the 1990s

However, the situation soon changed. In the elections to the Polish Sejm in September 1997, the right-wing party, "The Election Action of Solidarity," won. In Bulgaria in April of the same year, right-wing forces also won parliamentary elections. In Slovakia in May 1999, in the first presidential election, R. Schuster, a representative of the Democratic Coalition, won. In Romania, after the December 2000 election, I. Iliescu, the leader of the socialist party, returned to the presidency.

V. Havel remains president of the Czech Republic. In 1996, during the parliamentary elections, the Czech people deprived V. Klaus, the Prime Minister, of support. He lost his post at the end of 1997.

The formation of a new structure of society began, which was facilitated by political freedoms, an emerging market, and high activity of the population. Political pluralism is becoming a reality. For example, in Poland by this time there were about 300 parties and various organizations - social-democratic, liberal, Christian-democratic. Individual pre-war parties have revived, for example, the National-Tsarist Party that existed in Romania.

However, despite some democratization, there are still manifestations of "hidden authoritarianism", which is expressed in the high personification of politics, the style of government. The monarchist sentiments that have increased in a number of countries (for example, Bulgaria) are indicative. Former King Michael in early 1997, citizenship was returned.