The future Empress Maria Alexandrovna was born in 1824 in Darmstadt - the capital of Hesse. The baby was called Maximilian Wilgemina Augusta Sofia Maria.

Origin

Her father was the German Ludwig II (1777–1848) - the Grand Duke of Hesse and the Rhine. He came to power after the July Revolution.

The girl's mother was Wilhelmina of Baden (1788–1836). She was from the Baden house of Zeringen. At the court, there were rumors that her youngest children, including Maximilian, were born from a relationship with one of the local barons. Ludwig II - the official husband - recognized her as his daughter in order to avoid a shameful scandal. Nevertheless, the girl with her brother Alexander began to live separately from her father and his residence in Darmstadt. This place of "exile" was Heiligenberg, which was the property of Wilhelmina's mother.

Meeting with Alexander II

The Romanovs were popular dynastic marriages with German princesses. For example, the predecessor of Mary - Alexandra Fedorovna (wife of Nicholas I) - was the daughter of the Prussian king. And the wife of the last Russian emperor was also from the Hessian house. So against this background, the decision of Alexander II to marry a German from a small principality does not seem strange.

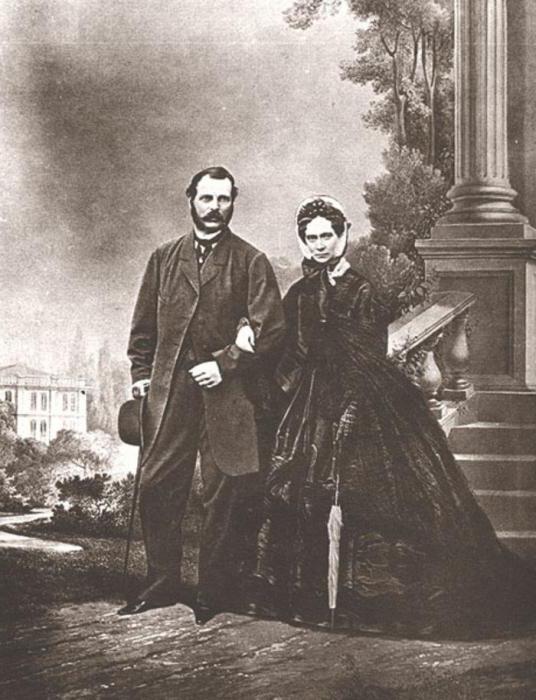

Empress Maria Alexandrovna met her future husband in March 1839, when she was 14 years old and he was 18. At that time, Alexander made the traditional European tour to get acquainted with the local ruling houses as heir to the throne. He met the daughter of the Duke of Hesse at the performance of Vestal.

How was the marriage agreed?

After meeting, Alexander began in letters to persuade parents to give permission to marry a German woman. However, the mother was against such a relationship of the prince. She was embarrassed by rumors about the girl’s illegal origin. Emperor Nicholas, on the contrary, decided not to chop off his shoulder, but to consider the matter more carefully.

The fact is that his son Alexander already had a bad experience in his personal life. He fell in love with the maid of honor of the yard Olga Kalinovskaya. Parents were strongly opposed to such a relationship for two fundamental reasons. Firstly, this girl was of simple origin. Secondly, she was also a Catholic. So Alexander was forcibly separated from her and sent to Europe, just so that he could find himself a suitable party.

So Nikolai decided not to risk it and not break his son’s heart again. Instead, he began to question in detail about the girl, the trustee, Alexander Kavelin, and the poet Vasily Zhukovsky, who accompanied the heir on his journey. When the emperor received positive reviews, an order immediately followed throughout the court stating that it was forbidden to spread any rumors about the Princess of Hesse from now on.

Even Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna had to obey this command. Then she decided to go to Darmstadt herself in order to meet her daughter-in-law in advance. It was an unheard of event - a similar thing had not happened in Russian history.

Appearance and interests

The future Empress Maria Alexandrovna made a wonderful impression on her predecessor. After the meeting in person, consent to marriage was obtained.

What so attracted others in this German girl? The most detailed description of her appearance was left in her memoirs by her maid of honor Anna Tyutcheva (daughter of the famous poet). According to her, the Empress Maria Alexandrovna had a delicate skin color, wonderful hair and the meek look of large blue eyes. Against this background, her thin lips, which often depicted an ironic smile, looked a little strange.

The girl had a deep knowledge of music and European literature. Her education and breadth of interests impressed everyone around her, and many people later left their rave reviews in the form of memoirs. For example, the writer Aleksei Konstantinovich Tolstoy said that the empress with her knowledge not only stands out from the rest of the women, but even noticeably outperforms many men.

Court Appearance and Wedding

The wedding took place shortly after all the formalities were settled. The bride arrived in St. Petersburg in 1840 and was most shocked by the splendor and beauty of the Russian capital. In December, she converted to Orthodoxy and was baptized with the name of Maria Alexandrovna. The very next day there was a betrothal between her and the heir to the throne. The wedding took place a year later, in 1841. It took place in the Cathedral Church, located in the Winter Palace of St. Petersburg. Now it is one of the premises of the Hermitage, where regular exhibitions are held.

It was hard for the girl to wedge herself into a new life because of her lack of knowledge of the language and the fear of not liking her mother-in-law and mother-in-law. As she later confessed, every day Maria spent as if on needles, felt like a “volunteer”, ready to rush anywhere at a sudden command, for example, at an unexpected reception. Secular life in general was a burden for the crown princess, and then the empress. First of all, she was attached to her husband and children, tried to do only to help them, and not waste time on formalities.

The coronation of the couple occurred in 1856 after the death of Nicholas I. Thirty-year-old Maria Alexandrovna received a new status, which frightened her all the time that she was the daughter-in-law of the emperor.

Character

Contemporaries noted the numerous virtues possessed by the Empress Empress Maria Alexandrovna. This is kindness, attention to people, sincerity in words and deeds. But the most important and noticeable was the sense of duty with which she stayed at court and held the title through her whole life. Each of her actions corresponded to imperial status.

She always respected religious dogmas and was extremely devout. This feature was so strongly distinguished in the character of the empress that it was much easier to imagine her as a nun than a reigning person. For example, Ludovig II (King of Bavaria) noted that Maria Alexandrovna was surrounded by a holy halo. Such behavior in many ways did not coincide with its status, since in many state (even formal) cases its presence was required, contrary to its behavior detached from worldly vanity.

Charity

Most of all, Empress Maria Alexandrovna - the wife of Alexander 2 - was known for her wide charity. Hospitals, orphanages and gymnasiums, which received the Mariinsky epithet, were opened all over the country at its expense. In total, she opened and monitored 5 hospitals, 36 shelters, 12 almshouses, 5 charitable societies. The empress did not deprive attention of the sphere of education either: two institutes, four dozen gymnasiums, hundreds of small schools for artisans and workers, etc. were built. Maria Alexandrovna spent both state and her own funds on this (she was given 50 thousand silver rubles a year for personal expenses).

Health care has become a special area of activity that Empress Maria Alexandrovna was engaged in. The Red Cross appeared in Russia precisely on its initiative. His volunteers helped the wounded soldiers during the war in Bulgaria against Turkey 1877-1878.

Death of daughter and son

A great tragedy for the royal family was the death of the heir to the throne. Empress Maria Alexandrovna - wife of Alexander 2 - gave the spouse eight children. The eldest son Nikolai was born in 1843, two years after the wedding, when his namesake grandfather was king.

The child was distinguished by a sharp mind and a pleasant character, for which he was loved by all family members. He was already engaged and educated when, as a result of an accident, he injured his back. There are several versions of what happened. Either Nikolai fell from his horse, or hit a marble table during a comic fight with his comrade. At first, the injury was imperceptible, but over time, the heir became paler and felt worse. In addition, doctors treated him incorrectly - they prescribed medications for rheumatism, which did not bring benefits, because the true cause of the disease was not revealed. Soon Nikolai was confined to a stroller. This became the terrible stress that Empress Maria Alexandrovna suffered. The son’s illness followed the death of Alexandra’s first daughter, who died of meningitis. His mother was constantly with Nikolay, even when it was decided to send him to Nice for treatment for tuberculosis of the spine, where he died at 22.

Cool relationship with husband

Both Alexander and Maria in their own way hardly experienced this loss. The emperor blamed himself for making his son do a lot of physical training, partly because of which an accident occurred. One way or another, but the tragedy alienated the spouses from each other.

The trouble was that their whole subsequent life together consisted of the same rituals. In the mornings, it was a kiss on duty and ordinary conversations about dynastic affairs. In the afternoon, the couple met another parade. The empress spent the evening with the children, and her husband constantly disappeared on state affairs. He loved the family, but his time was simply not enough for relatives, which Maria Alexandrovna could not help but notice. The empress tried to help Alexander in matters, especially in the early years.

Then (at the beginning of the reign), the king gladly consulted with his wife about many decisions. She was always up to date with the latest ministerial reports. Most often, her advice concerned the education system. This was largely due to the charity work that Empress Maria Alexandrovna was engaged in. And the development of education in these years has received a logical push forward. Schools were opened, access to them appeared among peasants, who, among other things, were also freed from serfdom under Alexander.

The empress herself had on this score the most liberal opinion shared, for example, with Kavelin, telling him that she strongly supported her husband in his desire to give freedom to the most numerous estate of Russia.

However, with the advent of the Manifesto (1861), the empress was less and less concerned with state affairs due to some cooling of relations with her husband. This was also due to the wayward nature of Romanov. The Tsar was increasingly overtaken by a whisper in the palace that he too often looked back at the opinion of his wife, that is, she was under her heel. This annoyed the freedom-loving Alexander. In addition, the title of the autocrat himself obliged him to make decisions only of his own free will, without advice from anyone. This concerned the very nature of power in Russia, which was believed to be given from God to the only anointed one. But the real gap between the spouses was yet to come.

Ekaterina Dolgorukova

In 1859, Alexander II conducted maneuvers in the southern part of the empire (the territory of present-day Ukraine) - the 150th anniversary of the battle of Poltava was celebrated. The sovereign stopped on a visit to the estate of the famous Dolgorukovs' house. This genus was a branch from the princes of Rurikovich. That is, his representatives were distant relatives of the Romanovs. But in the middle of the XIX century, the noble family was in debt, like in silk, and its head, Prince Mikhail, had only one estate left - Teplovka.

The emperor got into position and helped Dolgorukov, in particular, placed his sons in the guard, and sent his daughters to the Smolny Institute, promising to pay the expenses from the royal purse. Then he met with the thirteen-year-old Ekaterina Mikhailovna. The girl surprised him with her curiosity and love of life.

In 1865, the autocrat traditionally paid a visit to the Smolny Institute of noble maidens. Then, after a long break, he again saw Catherine, who was already 18 years old. The girl was amazingly beautiful.

The emperor, who had an amorous disposition, began to send her gifts through his assistants. He even began to visit the institute incognito, but it was decided that this was too much, and the girl was expelled under the pretext of poor health. Now she lived in St. Petersburg and saw the king in the Summer Garden. She was even made the maid of honor of the mistress of the Winter Palace, of which the Empress Maria Alexandrovna was. The wife of Alexander the Second was heavily worried about rumors swarming around a young girl. Finally, Catherine left for Italy, so as not to cause a scandal.

But Alexander was serious. He even promised the favorite that he would marry her as soon as the opportunity presented itself. In the summer of 1867 he arrived in Paris at the invitation of Napoleon III. Dolgorukova went there from Italy.

In the end, the emperor tried to communicate with his family, wanting to be heard first of all by Maria Alexandrovna. The Empress, the wife of Alexander II and the mistress of the Winter Palace, tried to keep up appearances and did not allow the conflict to go beyond the residence. However, her eldest son and heir to the throne rebelled. This was not surprising. The future Alexander III was distinguished by a steep disposition, even at a very young age. He scolded his father, and he, in turn, was furious.

As a result, Catherine still moved to the Winter Palace and gave birth to four children from the king, who later received princely titles and were legalized. This happened after the death of the legal wife of Alexander. The funeral of Empress Maria Alexandrovna gave the king the opportunity to marry Catherine. She received the title of His Serene Princess and the surname Yurievskaya (like her children). However, the emperor was not happy for long in this marriage.

Illness and death

The health of Maria Alexandrovna was undermined for many reasons. These are frequent births, betrayal of the husband, death of the son, as well as the damp climate of St. Petersburg, for which the native German was not ready in the first years of the move. Because of this, she began to consume, as well as nervous exhaustion. According to the recommendation of a personal doctor, a woman went south to the Crimea every summer, whose climate was supposed to help her overcome the disease. Over time, the woman almost retired. One of the last episodes of her participation in public life was a visit to military councils during the confrontation with Turkey in 1878.

In these years, assassination by revolutionaries and bombers was constantly carried out on Alexander II. Once the explosion occurred in the dining room of the Winter Palace, but the empress was so ill that she did not even notice it, lying in her chambers. And her husband survived only because he lingered in his office, contrary to the habit of having lunch at the appointed time. Constant fear for the life of her beloved husband ate the remnants of health that Maria Alexandrovna still owned. The empress, whose photos at that time showed a clear change in her appearance, was extremely emaciated and looked more like her shadow than a person in her body.

In the spring of 1880, she finally fell down, while her husband moved to Tsarskoye Selo with Dolgorukova. He paid his wife short visits, but could not do anything to somehow improve her well-being. Tuberculosis became the reason why Empress Maria Alexandrovna died. The biography of this woman says that her life ended in the same year, June 3, according to a new style.

The wife of Alexander II found the last refuge according to dynastic tradition in the Peter and Paul Cathedral. The funeral of Empress Maria Alexandrovna became a mourning event for the whole country, sincerely loved her.

Alexander briefly survived his first wife. In 1881, he died after being injured in an explosion of a bomb thrown at his feet by a terrorist. The emperor was buried next to Maria Alexandrovna.