Roman military ammunition and weapons were produced during the expansion of the empire in large quantities according to established models, and they were used depending on the category of troops. These standard models were called res militares. The constant improvement of the protective properties of armor and the quality of weapons, the regular practice of its use led the Roman Empire to military superiority and numerous victories.

The equipment gave the Romans a clear advantage over their enemies, especially with regard to the strength and quality of their “armor”. This does not mean that a simple soldier had better equipment than rich people among his opponents. According to Edward Lattwack, their military equipment was not of better quality than that used by most opponents of the Empire, but armor significantly reduced the number of deaths among the Romans on the battlefield.

Military features

Initially, the Romans produced weapons based on the experience and examples of Greek and Etruscan masters. They learned a lot from their opponents, for example, when confronted with the Celts, they adopted some types of equipment, they borrowed a helmet model from the Gauls, and the anatomical carapace from the ancient Greeks Thorax.

As soon as Roman armor and weapons were officially accepted by the state, they became the standard for almost the entire imperial world. Standard weapons and ammunition changed several times during the long Roman history, but they were never individual, although each soldier decorated his armor at his own discretion and “pocket”. However, the evolution of the weapons and armor of the warriors of Rome was quite long and complex.

Pugio Daggers

Pugio was a dagger that was borrowed from the Spaniards and was used by Roman soldiers as weapons. Like other legionnaire equipment items, it underwent some changes during the 1st century. As a rule, he had a large leaf-shaped blade with a length of 18 to 28 cm and a width of 5 cm or more. The middle “vein” (groove) passed along the entire length of each side of its cutting part, or simply protruded only from the front. The main changes: the blade became thinner, approximately 3 mm, the handle was made of metal and inlaid with silver. A distinctive feature of the pugio was that it could be used both for stabbing and from top to bottom.

History

Around 50 AD a rod version of the dagger was introduced. This in itself did not lead to significant changes in the appearance of the pugio, but some of the later blades were narrow (less than 3.5 cm wide), had a small or absent "waist", although they remained double-edged.

Throughout the entire period of their use as part of the ammunition of the handle remained approximately the same. They were made either from two layers of the horn, or a combination of wood and bone, or covered with a thin metal plate. Often the hilt was decorated with silver inlay. She was 10-12 cm long, but rather narrow. An extension or a small circle in the middle of the handle made the grip more reliable.

Gladius

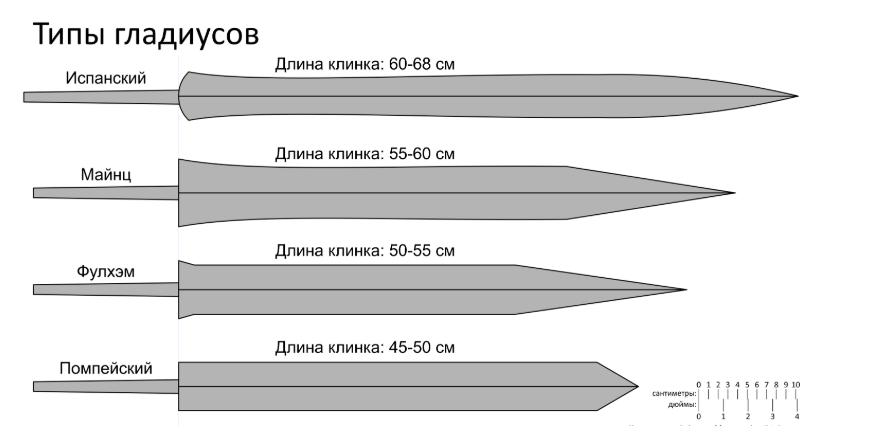

It was customary to call any kind of sword, although in the days of the Roman Republic the term gladius Hispaniensis (the Spanish sword) referred (and still refers) specifically to the average length of the weapon (60 cm-69 cm), which was used by Roman legionnaires from the 3rd century BC.

Several different models are known. Among the collectors and historical reenactors, the two main types of swords are known as gladius (in the places where they were found during excavations) - Mainz (short version with a blade length of 40-56 cm, a width of 8 cm and a weight of 1.6 kg) and Pompeii (length from 42 up to 55 cm, width 5 cm, weight 1 kg). Later archaeological finds confirmed the use of an earlier version of this weapon: a long sword that was in service with the Celts and was adopted by the Romans after the Battle of Cannes. Legionnaires wore their swords on their right thighs. By the changes that have occurred with the gladius, one can trace the evolution of the weapons and armor of the warriors of Rome.

Spata

This was the name of any sword in late Latin (spatha), but most often one of the long versions characteristic of the middle era of the Roman Empire. In the 1st century, the Roman cavalry began to use longer double-edged swords (from 75 to 100 cm), and at the end of the 2nd or beginning of the 3rd century, the infantry also used them for some time, gradually moving to carrying spears.

Gasta

This is a Latin word meaning "piercing spear." The Gastas (in some versions of the Hastas) were in service with the Roman legionnaires, later these soldiers were called Gastatis. However, in republican times, they were rearmed with pilum and gladius, and only the triaries still used these spears.

They were about 1.8 meters (six feet) long. The shaft was usually made of wood, while the “head” was made of iron, although early versions had bronze tips.

There were lighter and shorter spears, such as those used by the velites (quick reaction troops) and legions from the beginning of the republic.

Pilum

Pilum (the plural of pila) was a heavy throwing spear two meters long and consisted of a shaft, from which stood an iron shank with a diameter of about 7 mm and a length of 60 -100 cm with a pyramidal head. Pilum usually weighed two to four kilograms.

The spears were designed to pierce both the shield and armor at a distance, but if they just got stuck in them, they were difficult to remove. The iron shank was bent on impact, aggravating the enemy’s shield and preventing the immediate reuse of pilum. With a very strong blow, the shaft could break, leaving the enemy with a curved shank in the shield.

Roman archers (sagittarius)

Archers were armed with complex bows (arcus), shooting arrows (sagitta). This type of "long-range" weapon was made from the horns, wood, and tendons of animals held together by glue. As a rule, sagittarios (a kind of gladiators) took part exclusively in large-scale battles, when an additional massive blow to the enemy at a distance was required. This weapon was later used for training recruits on arcubus ligneis with wooden inserts. Reinforcing planks have been found in many excavations, even in the western provinces, where wooden bows were traditional.

Heroballista

Also known as manuballist. She was a crossbow, which was sometimes used by the Romans. The ancient world knew many options for mechanical hand weapons, similar to a late medieval crossbow. Accurate terminology is the subject of ongoing scientific debate. Roman authors, for example, Vegetius, repeatedly note the use of small arms, for example, arcuballista and manuballista, respectively cheiroballista.

Although most scholars agree that one or more of these terms refers to hand throwing weapons, there is disagreement over whether these were bent or mechanized bows.

The Roman commander Arrian (c. 86 - after 146) describes in his treatise on the Roman cavalry "Tactics" the firing of a mechanical hand weapon from a horse. The sculptural bas-reliefs in Roman Gaul depict the use of crossbows in hunting scenes. They are surprisingly similar to a late medieval crossbow.

Heroballist foot soldiers carried dozens of lead throwing darts called plumbatae (from plumbum, which means “lead”), with an effective range of up to 30 m, which is much larger than that of a spear. Darts were attached to the back of the shield.

Digging tools

Ancient writers and politicians, including Julius Caesar, documented the use of shovels and other digging tools as important tools of war. The Roman Legion, on the march, dug a ditch and rampart every night around its camps. They were also useful as an impromptu weapon.

Armor

Not all troops wore reinforced Roman armor. Light infantry, especially in the early republic, made little or no use of armor. This allowed both to move faster and to reduce the cost of army equipment.

Legionary soldiers of the 1st and 2nd centuries used various types of protection. Some wore chain mail, while others wore scaly Roman armor or segmented lorik, or cuirass with metal plates.

This latter type was a complex part of the armament, which in certain circumstances provided excellent protection for chain mail (lorica hamata) and scaly armor (lorica squamata). Modern spear trials have shown that this species was impenetrable for most direct hits.

However, without a lining it was inconvenient: the reenactors confirmed that wearing clothes known as subarmalis freed the wearer from bruises that appeared both during prolonged wearing of armor and from a blow inflicted by an armor on a weapon.

Auxilia

In the 3rd century, troops are depicted in chain mail Roman armor (mostly) or in standard 2nd century auxilia. The artistic report confirms that most of the soldiers of the late Empire wore metal armor, despite the allegations of Vegetius to the contrary. For example, illustrations in the Notitia treatise show that gunsmiths made chain mail armor at the end of the 4th century. They also produced the gladiators of ancient Rome.

Roman armor of Loric Segment

It was an ancient type of body armor and was mainly used at the beginning of the Empire, but this Latin name was first used in the 16th century (the ancient form is unknown). The Roman armor itself consisted of wide iron strips (hoops) attached to the back and chest with leather straps.

The stripes were located horizontally on the body, overlapping each other, they surrounded the body, fastened in front and behind with the help of copper hooks, which were connected by leather laces. The upper body and shoulders were protected by additional bands (“shoulder protectors”) and chest and back plates.

The armor form of the Roman legionnaire could be folded very compactly, since it was divided into four parts. During its use, it has been modified several times: the currently recognized types are Kalkriese (c. 20 BC to 50 AD), Corbridge (c. 40 BC to 120) and Newstead (c. 120, possibly at the beginning of the 4th century).

There is a fourth type, known only from the statue found in Alba Giulia in Romania, where, apparently, there was a “hybrid” option: the shoulders are protected by scaly armor, and the hoops of the body are smaller and deeper.

The earliest evidence of wearing lorica segmantata dates from around 9 BC. e. (Dangstetten). The armor of the Roman legionnaire was used for quite some time: up to the 2nd century AD, judging by the number of finds of that period (more than 100 places are known, many of them in Britain).

However, even in the 2nd century AD, a segmentate never replaced a lorika with a hamat, as it still remained a standard form for both heavy infantry and cavalry. The last recorded use of this armor dates back to the end of the 3rd century AD (Leon, Spain).

There are two opinions regarding who used this form of armor of Ancient Rome. One of them states that only for the legionnaires (heavy infantry of the Roman legions) and Praetorians were released lorica segment. Auxiliary forces more often wore lorika hamatu or squamata.

The second point of view is that both the legionnaires and auxiliary soldiers used the armor of the Roman warrior of the “segmentate” type, and this is confirmed to some extent by archaeological finds.

Lorika segmentation provided greater protection than a hamat, but it was also more difficult to produce and repair. The costs associated with making segments for this type of armor in Rome may explain the return to ordinary chain mail after the 3rd – 4th century. At that time, trends in the development of military force were changing. Alternatively, all types of Roman warrior armor could no longer be used, as the need for heavy infantry was reduced in favor of fast mounted troops.

Lorika Hamata

It was a type of chain mail used in the Roman Republic and spread throughout the Empire as standard Roman armor and weapons for the primary heavy infantry and secondary troops (auxilia). It was mainly made of iron, although bronze was sometimes used instead.

The rings were tied together, alternating closed elements in the form of washers with rivets. This gave a very flexible, reliable and durable armor. Each ring had an inner diameter of 5 to 7 mm and an outer diameter of 7 to 9 mm. On the shoulders of the lorika of the hamat there were flaps similar to the shoulders of the Greek linothorax. They started from the middle of the back, went to the front of the body and were connected by copper or iron hooks, which were attached to studs riveted through the ends of the flaps. Several thousand rings made up one lorik of the hamat.

Although production is labor intensive, it is believed that with good maintenance they could be used continuously for several decades. The usefulness of the armor was such that the late appearance of the famous lorika segment, which provided greater protection, did not lead to the complete disappearance of the hamata.

Lorica Squamata

Lorica squamata was a type of scaly armor used during the Roman Republic and in later periods. It was made of small metal scales sewn to a fabric base. It was worn, and this can be seen in ancient images, ordinary musicians, centurions, cavalry troops and even auxiliary infantry, but legionnaires could also wear it. The shirt of the armor was formed in the same way as the lorika of the hamat: from the middle of the thigh with reinforcing shoulders or equipped with a cape.

Individual scales were either iron or bronze, or even alternating metals on the same shirt. The plates were not very thick: from 0.5 to 0.8 mm (from 0.02 to 0.032 inches), which may have been the usual range. However, since the scales overlapped in all directions, several layers provided good protection.

Size ranged from 6 mm (0.25 in) wide to 1.2 cm high, up to 5 cm (2 in) wide and 8 cm (3 in) high, with the most common sizes being about 1.25 2.5 cm. Many had rounded bottoms, while others had pointed or flat bases with cut corners. The plates could be flat, slightly convex, or have a raised middle membrane or edge. All of them on the shirt were basically the same size, but the scales from different chain mails were significantly different.

They were connected in horizontal rows, which are then sewn to the substrate. Thus, each of them had from four to 12 holes: two or more on each side for attaching to the next in a row, one or two at the top for attaching to the substrate, and sometimes at the bottom for attaching to the base or to each other.

The shirt could be opened either at the back or at the bottom on one side, so that it was easier to put on, and the hole was pulled together with ties. Much has been written about the alleged vulnerability of these ancient Roman armor.

No specimens of the whole squamous lorica of squamata were found, but there were several archaeological finds of fragments of such shirts. The original Roman armor is quite expensive and affordable only for extremely wealthy collectors.

Parma

It was a round shield with three Roman feet across. It was smaller than most shields, but it was solidly made and was considered effective protection. This was ensured by the use of iron in its structure. He had a pen and a shield (umbo). Finds of Roman armor are often removed from the earth complete with these shields.

Parma was used in the Roman army by units of the lower class: velites. Their equipment consisted of a shield, a dart, a sword and a helmet. Parma was later replaced by a scutum.

Roman helmets

Galea or cassis were very different in form. One of the earliest types was the Montefortino bronze helmet (cup-shaped with a rear visor and side protective plates), which was used by the armies of the Republic until the 1st century AD.

It was replaced by Gallic counterparts (they were called "imperial"), providing on both sides protection for the soldier’s head.

Today they are very fond of making craftsmen who create armor of Roman legionnaires with their own hands.

Baldrick

In other words, a boldrik, a boudric, a bouldric, as well as other rare or outdated pronunciation variants is a belt worn on one shoulder, which is usually used to carry a weapon (usually a sword) or another weapon, such as a forge or drum. A word can also refer to any belt as a whole, but its use in this context is perceived as poetic or archaic. These belts were an indispensable attribute of Roman armor.

Application

Baldrics have been used since ancient times as part of military clothing. Without exception, all the soldiers wore belts with their Roman armor (some photos are in this article). The design provided greater weight support compared to a standard waist belt, without restricting hand movements and providing easy access to a portable item.

In later times, for example, in the British army of the late 18th century, they used a pair of white baldriks crossed on their chests. As an alternative, especially in our time, it can perform a ceremonial role, not a practical one.

Baltey

In ancient Roman times, balthus (or ballets) was the type of baldric commonly used to hang a sword. It was a belt that was worn over the shoulder and passed obliquely down to the side, usually of leather, often adorned with precious stones, metals, or both.

There was also a similar belt worn by the Romans, especially soldiers, and called a Sintu, which was fastened around the waist. He was also an attribute of Roman anatomical armor.

Many non-military or paramilitary organizations include the Ballets as part of their formal attire. The 4th-degree Color Corps of the Knights of Columbus uses it as an element of his uniform. Baltey supports the ceremonial (decorative) sword. The reader can see the photo of the armor of the Roman legionnaires together with the ballets in this article.

Roman belt

Cingulum Militaryare is part of the ancient Roman military ammunition in the form of a belt, decorated with metal fittings, which soldiers and officials wore as a rank. Many examples have been found in the Roman province of Pannonia.

Kaligi

Caligi were heavy boots with thick soles. Caliga comes from the Latin callus, which means "hard." Named because the hobnails were nailed into the leather soles before being sewn onto a softer leather lining.

They were worn by the lower ranks of the Roman cavalry and infantry, and perhaps some centurions. A strong connection with the Kalig ordinary soldiers is obvious, since the latter were called Kaligati ("loaded"). At the beginning of the first century AD, the soldiers nicknamed the two or three-year-old Guy “Caligula” (“little boot”) because he wore miniature soldier's clothing complete with viburnum.

They were stronger than closed boots. In the Mediterranean, this could be an advantage. In the cold and humid climate of northern Britain, additional woven socks or wool in the winter could help isolate the legs, but the caligas were replaced there by the end of the second century AD with more practical "closed boots" (carbatinae) in a civilian style.

By the end of the 4th century, they began to be used throughout the Empire. Emperor Diocletian's Price Decree (301) includes the stated price for unattended carbatinae made for civil men, women and children.

Kalig's sole and openwork upper were cut from a single piece of high-quality cow or bovine skin. The bottom was attached to the midsole with snaps, usually made of iron, but sometimes made of bronze.

The fixed ends were covered with an insole. Like all Roman shoes, Kalig was flat-soled. She was laced in the center of the foot and on top of the ankle. Isidore of Seville believed that the name "caliga" comes from the Latin "callus" ("hard skin") or from the fact that the boot was laced or tied (ligere).

Shoe styles ranged from manufacturer to manufacturer and from region to region. The placement of nails in it is less variable: they functioned to provide support to the foot, as modern sports shoes do. At least one provincial manufacturer of army boots has been identified by name.

Pteruga

These are sturdy skirts made of leather or multilayer fabric (linen), and Roman and Greek warriors wore stripes or lappets sewn on them. Also in a similar way strips similar to epaulettes protecting the shoulders were sewn on their shirts. Both sets are usually interpreted as belonging to the same clothes worn under the cuirass, although in the linen version (linothorax) they could be non-removable.

The cuirass itself can be built in different ways: lamellar-bronze, linothorax, from scales, lamellar or chain-link version. Pads can be arranged in the form of one row of longer strips or two layers of short, overlapping graduated length blades.

In the Middle Ages, especially in Byzantium and the Middle East, such strips were used at the back and sides of helmets to protect the neck, while leaving it free enough for movement. However, no archaeological remains of leather helmets have been discovered. Artistic images of such elements can also be interpreted as vertically stitched quilted textile protective coatings.