Description of the sky is a task that has occupied the minds of many thinkers throughout history. The combination of disparate stars into figures, an understanding of the logic of the movement of the stars was necessary both for orientation on the ground and for building a philosophical system that explains the laws and structure of the universe.

Union of stars

The human brain is designed so that in any chaotic arrangement of objects, he tries to discern logic, to see a familiar silhouette behind scattered and unconnected points. A map of the sky without this property would never have been born. Since the beginning of the first civilizations, people have been fascinated by the night sky and have seen familiar images on it: gods, heroes, objects. So the first constellations appeared. They were a union of neighboring luminaries in a specific pattern. Constellations made it easier to remember the location of the stars and, as a result, orientation on the ground with their help.

Initially, the description of the starry sky was a set of constellations, often overlapping each other. Part of the luminaries could relate immediately to two celestial drawings, and some areas remained deprived: due to the small number of stars in such territory they were not connected to any constellations.

Structuring

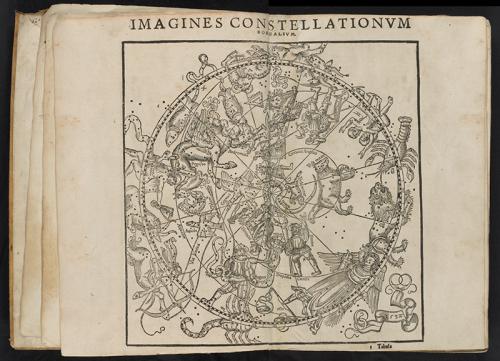

The description of the sky in the form of a map with the designation of the constellations first appeared in the II century BC. e. It was made by Hipparchus of Nicaea, one of the greatest Greek astronomers. His sky map contained 48 constellations and was complemented by a catalog of 850 stars. A little later, in the II century BC. e., this list was supplemented by Ptolemy. His famous work “Almagest” already contained 1022 stars, broken into the same 48 constellations.

For quite a long time, up to the beginning of the 17th century, the work of Ptolemy, at least for European astronomy, remained the main one, although throughout this period the list of constellations was supplemented by new ones. Heavenly drawings arose mainly in those parts of the sky that were not available for observation by Ptolemy. In the 17th century, Jan Hevelius, a Polish scientist, expanded the list of luminaries to 1533 and created his famous star atlas “Uranography” with beautiful drawings. He added several new constellations.

IAU General Assembly

However, the description of the sky made by Hevelius was not like the modern one. It began to acquire familiar features only in 1922, when the First General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union (IAC) met. It approved a list of 88 constellations, which are used today. Moreover, the very meaning of the term "constellation" has changed. Today, it is understood not as a certain number of luminaries that make up this or that figure, but a projection of the sky with all the space objects located on it. The boundaries of these sections underwent some changes and were finally approved in 1935.

Names

It is impossible to make a description of the night sky without knowing the names assigned to the constellations and individual stars. In international practice, the Latin names of heavenly drawings are used. This allows scientists of different countries to understand each other. However, in textbooks and popular literature on astronomy, each nation has translations of accepted designations into their native language. Often, it’s difficult to choose a unique equivalent. Therefore, for example, in our literature of different years, there are Hair Veronica and Hair Berenice, Hound dogs and Greyhounds and so on.

As for the designations of stars, the most striking of them have their own names, most often of Arab origin. All luminaries without exception have a scientific designation. In addition, since the sixteenth century it has been customary to label stars of a particular celestial pattern with the letters of the Greek alphabet in accordance with their brightness: alpha is the leader in this parameter, beta takes second place and so on.

Two hemispheres

The celestial sphere likewise the earthly sphere has its equator, which divides it into two parts. The sky of the Northern hemisphere looks different than the southern part of the sphere: other luminaries are located here. On the line of the celestial equator are constellations called equatorial. They are distinguished by the fact that they are available for observation almost anywhere in the world.

In the sky of the Northern Hemisphere, Ursa Minor has a special position. This small constellation is famous for its brightest point - the Polar Star, which always takes the same place unlike other luminaries. She points north. In the Southern Hemisphere there is no such bright "frozen" star. The role of the pointer to the pole is played by the constellation Southern Cross.

Zodiac

The description of the sky will be incomplete if we do not mention the constellations through which the visible path of all the planets, as well as the moon and the sun, lie. It's about the zodiac. Strictly speaking, it includes not accepted 12, but 13 constellations. An “additional” heavenly pattern is Ophiuchus through which the center of the Sun passes from November 30 to December 17. Interestingly, the zodiac circle in the sky as a whole does not strongly coincide with that accepted in astrology. The difference is not only the "extra" constellation, but also the time the Sun enters each of the heavenly figures, as well as the duration of its stay in them. For example, in the constellation Scorpio, our luminosity only visits a week from November 23 to 29.

Invisible

However, bright stars, close planets, as well as the sun and moon are not all that can be seen in the sky. With a telescope, the observer's abilities greatly increase, and he has a chance to see clusters of stars and planetary nebulae. Of course, the picture will not be the same as in the pictures of the famous Hubble, but it’s worth looking at it anyway.

However, even without special equipment, you can try to see distant neighboring galaxies. The Andromeda nebula is available for observation in the Northern Hemisphere, and the Magellanic Clouds, Big and Small, in the Southern.

The night sky attracts us with a sparkle of stars, cosmic secrets and riddles of a universal scale. Seeking to solve them, people from ancient times tried to make it easier to remember the location of the stars, for which they were combined into heavenly drawings and put on maps. With an increase in knowledge and improvement of equipment, the latter were only specified, acquired a slightly different structure. Today's description of the sky is more complicated and more accurate than what was during the time of Ptolemy, but we can say with confidence: even a hundred years later, children will begin to learn to correlate star charts with the sky above their heads from the search for the oldest celestial drawings described by this wise Greek.