Locke John, in The Experience of Human Understanding, states that almost all science, with the exception of mathematics and morality, and most of our everyday experience are subject to opinion or judgment. We base our judgments on the similarity of sentences with our own experience and with the experiences that we have heard from others.

"The Experience of Human Understanding" - Locke's fundamental work

Locke examines the connection between reason and faith. He defines the mind as the ability that we use to gain judgment and knowledge. Faith is, as John Locke writes in The Experience of Human Understanding, recognition of revelation and has its own truths that the mind cannot detect.

Reason, however, should always be used to determine which revelations are truly revelations from God and which are human constructs. Finally, Locke divides all human understanding into three sciences:

- natural philosophy, or the study of things to gain knowledge;

- ethics, or learning how best to act;

- logic, or the study of words and signs.

So, let’s analyze some of the main ideas presented in John Locke’s book “The Experience of Human Understanding”.

Analysis

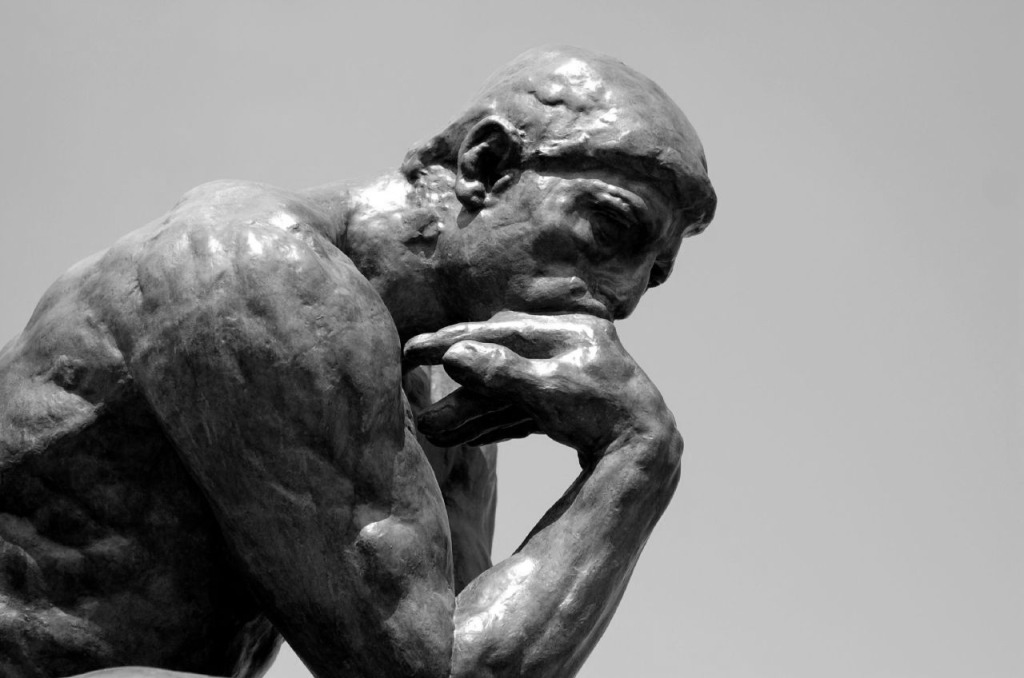

In his work, Locke actually shifted the focus of seventeenth-century philosophy to metaphysics, to the basic problems of epistemology and how people can acquire knowledge and understanding. It severely limits many aspects of human understanding and the functions of the mind. His most striking innovation in this regard is his rejection of the theory of the birth of people with innate knowledge, which philosophers like Plato and Descartes tried to prove.

Idea of tabula rasa

Locke replaces the theory of innate knowledge with his own concept of signature, tabula rasa or "blank board". With his ideas, John Locke is trying to demonstrate that each of us is born without any knowledge: we are all “clean boards” at birth.

Locke makes a strong argument against the existence of innate knowledge, but the model of knowledge that he offers in his place is not without flaws. By emphasizing the need for experience as a prerequisite for knowledge, Locke lowers the role of the mind and neglects an adequate consideration of how knowledge exists and is retained in consciousness. In other words, how do we remember information and what happens to our knowledge when we do not think about it, and it is temporarily outside our consciousness. Although John Locke discusses in detail in the Experience of Human Understanding which objects of experience may be known, he leaves the reader with little idea of how the mind works to translate experience into knowledge and combine certain experience with other knowledge to classify and interpret the future. information.

Locke presents “simple” ideas as the basic unit of human understanding. He claims that we can break down all our experience into these simple, fundamental parts that cannot be "crushed" further. For example, in a book, John Locke presented his idea through a simple wooden chair. It can be broken down into simpler units that are perceived by our minds through one meaning, through multiple feelings, through reflection, or through a combination of sensation and reflection. Thus, the “chair” is perceived and understood by us in several ways: both brown and hard, both in accordance with its function (to sit on it), and as a specific shape that is unique to the object “chair”. These simple ideas allow us to understand what a “chair” is and to recognize it when we contact it. In general, in philosophy, cognition is a single or prolonged mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thinking, experience and feelings. Apparently, Locke perceived this process a little differently.

Sources

In this regard, Locke's philosophy with his theory of primary and secondary qualities is based on the corpuscular hypothesis of Robert Boyle, a friend of Locke and his contemporary. According to the corpuscular hypothesis, which Locke considered the best scientific picture of the world at one time, all matter consists of small particles or corpuscles that are too small, they are individual and colorless, tasteless, soundless and odorless. The location of these invisible particles of matter gives an object of perception of both its primary and secondary qualities. The main qualities of an object include its size, shape and movement.

For Locke in philosophy, cognition is a mental process associated with assessment, cognition, learning, perception, recognition, remembering, thinking and understanding, which lead to awareness of the world around us. They are primary in the sense that these qualities exist regardless of who perceives them. Secondary qualities include color, smell and taste, and they are secondary in the sense that they can be perceived by the observers of the object, but they are not inherent in the object. For example, the shape of the rose and the way it grows are primary, because they exist regardless of whether they are observed. Nevertheless, reddening of the rose exists only for the observer under the right lighting conditions, and if the observer's vision is functioning normally. John Locke, in The Experience of Human Understanding, suggests that since we can explain everything using only corpuscles and basic qualities, we have no reason to think that secondary qualities have a real foundation in the world.

Thinking and perception

According to Locke, every idea is an object of some kind of action of perception and thinking. The idea - in accordance with Locke's philosophy - is a direct object of our thoughts, that which we perceive and to which we actively pay attention. We also perceive some things without even thinking about them, and these things do not continue to exist in our minds, because we have no reason to think about them or remember them. The latter are objects with minimal values. When we perceive the secondary qualities of an object, we actually perceive that which does not exist outside our mind. In each of these cases, Locke maintained that the act of perception always has an internal object - the thing that is perceived exists in our minds. Moreover, the object of perception sometimes exists only in our minds.

The reviews of John Locke's Experience in Human Understanding show that one of the most confusing aspects of Locke's judgment is the fact that perception and thinking sometimes, but not always, are one and the same action.

Essence and being

Locke's discussion of the essence or being may seem confusing because Locke himself does not seem to be convinced of his existence. However, Locke's philosophy retains this concept for several reasons. First, he seems to believe that the idea of essence is necessary in order to understand our language. Secondly, the concept of essence solves the problem of perseverance through change. For example, if a tree is just a collection of ideas such as “tall,” “green,” “leaves,” etc., what should happen if the tree is short and leafless? Is this new set of qualities changing the essence of the "tree"?

From the contents of John Locke's Experience of Human Understanding, it becomes clear: the essence of the object is preserved despite any changes. The third reason Locke seems to be forced to accept the concept of essence is to explain what unites ideas that exist at the same time, turning them into one thing different from any other thing. The bottom line helps clarify this unity, although Locke is not very specific about how it works. For Locke, the bottom line is what are the qualities of the objects are dependent and which are independent.

Locke's Ideas in the Context of World Philosophy

Locke's opinion that our knowledge was much more limited than previously thought was shared by other thinkers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. For example, Locke was supported by Descartes and Hume, although Locke is very different from Descartes in understanding why this knowledge is limited.

Total

However, for Locke, the fact that our knowledge is limited is more philosophical than practical. Locke points out that the very fact that we do not take such skeptical doubts about the existence of the outside world is a sign that the vast majority of us are aware of the existence of the world.

The overwhelming clarity of the idea of the outside world and the fact that it is confirmed by all but the madmen is important for Locke in and of itself. However, Locke believes that we can never know the truth when it comes to natural science. Instead of prompting us to stop worrying about science, Locke says we should be aware of the limitations.