Phenomenology is a philosophical trend that developed in the 20th century. Its main task is to directly research and describe phenomena as consciously experienced, without theories about their causal explanations and as free as possible from undeclared prejudices and assumptions. However, the concept itself is much older: in the XVIII century, the German mathematician and philosopher Johann Heinrich Lambert applied it to that part of his theory of knowledge that distinguishes truth from illusion and error. In the 19th century, this word was mainly associated with the phenomenology of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who traced the development of the human spirit from simple sensory experience to "absolute knowledge."

Definition

Phenomenology is a study of the structures of consciousness from the point of view of the first person. The central structure of experience is its intentionality, its focus on something, be it experience or some object. Experience is directed at the object by virtue of its content or significance (which represents the object) together with the corresponding favorable conditions.

Phenomenology is a discipline and method of studying philosophy, developed mainly by German philosophers Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. It is based on the premise that reality consists of objects and events (“phenomena”), since they are perceived or understood in the human mind. The essence of the phenomenological method actually comes down to finding the evidence of each phenomenon.

This discipline can be considered as a branch of metaphysics and philosophy of the mind, although many of its supporters argue that it is connected with other key disciplines in philosophy (metaphysics, epistemology, logic and ethics). But different from others. And it provides a clearer view of philosophy, which has implications for all these other areas.

Briefly describing the phenomenological method, we can say that this is a study of experience and how a person experiences it. With its help, the structures of conscious experience are studied from the point of view of the subject or the first person, as well as its intentionality (the way in which experience is directed to a specific object in the world). All these are objects of the phenomenological method. Then it leads to an analysis of the conditions for the possibility of intentionality, conditions associated with motor skills and habits, background social practice, and often language.

What is studying

Experience in a phenomenological sense includes not only a relatively passive experience of sensory perception, but also imagination, thought, emotions, desire, will and action. In short, it includes everything that a person experiences or fulfills. Moreover, as Heidegger pointed out, people often do not realize the obvious habitual patterns of action, and the field of phenomenology can extend to semi-conscious and even unconscious mental activity. The objects of the phenomenological method are, firstly, unconditional evidence, and secondly, ideal cognitive structures. Thus, the individual can observe and interact with other things in the world, but does not really perceive them in the first place.

Accordingly, phenomenology in philosophy is the study of things as they appear (phenomena). This approach is often called descriptive rather than explanatory. The phenomenological method in philosophy differs, for example, from cause-effect or evolutionary explanations, which are inherent in the natural sciences. This is due to the fact that its main task is to give a clear, undistorted description of the ways things appear.

In total, two methods of phenomenological research are distinguished. The first is a phenomenological reduction. The second, direct contemplation as a methodology of phenomenology, boils down to the fact that it acts as a descriptive science, and only the data of direct intuition act as material.

Origin

The term "phenomenology" comes from the Greek phainomenon, which means "appearance." Therefore, this study of phenomena is the opposite of reality, and as such goes back to the Platonic Allegory of the Cave and its theory of Platonic idealism (or Platonic realism) or, possibly, even further - to Hindu and Buddhist philosophy. To varying degrees, the methodological skepticism of Rene Descartes, the empiricism of Locke, Hume, Berkeley and Mill, as well as the idealism of Immanuel Kant - all this played a role in the early stages of the development of the theory.

History of development

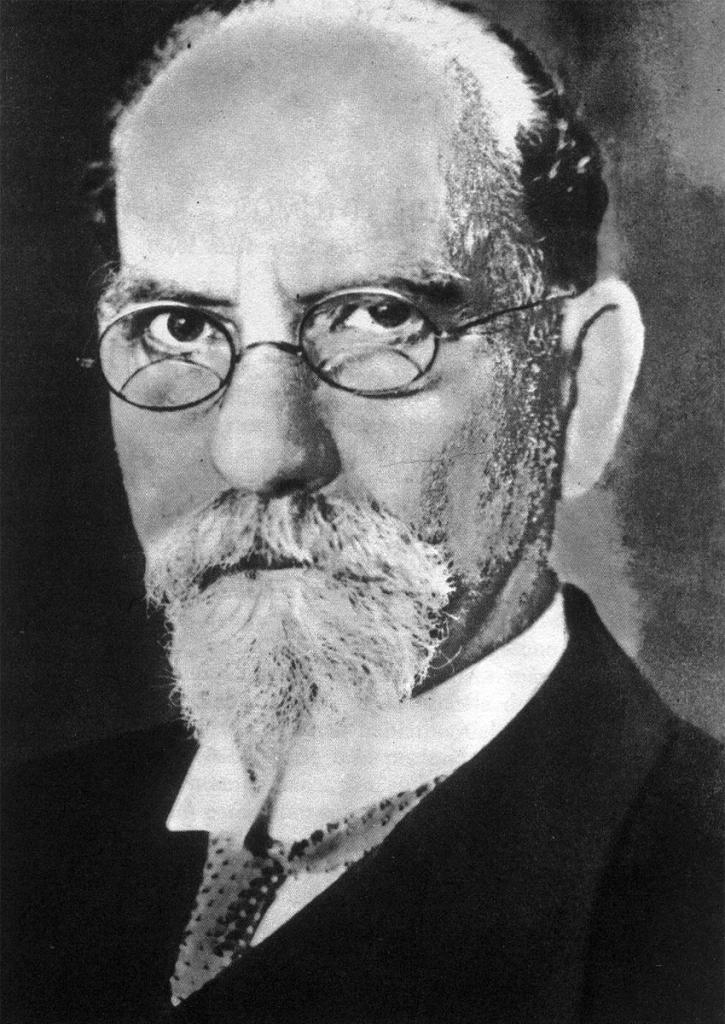

Phenomenology actually began with the work of Edmund Husserl, who first considered it in his 1901 Logical Investigations. However, one should also consider innovative work on intentionality (the notion that consciousness is always intentional or directed) by the teacher Husserl, the German philosopher and psychologist Franz Brentano (1838-1917) and his colleague Karl Stumpf (1848-1936).

Husserl first formulated his classical phenomenology as a kind of “descriptive psychology” (sometimes called realistic phenomenology), and then as a transcendental and eidetic science of consciousness (transcendental phenomenology). In his 1913 Ideas, he established a key distinction between an act of consciousness (noesis) and the phenomena on which it is directed (noemata). In a later period, Husserl focused more on ideal, essential structures of consciousness and introduced a method of phenomenological reduction specifically to eliminate any hypothesis about the existence of external objects.

Martin Heidegger criticized and expanded Husserl's phenomenological study (in particular in his Being and Time of 1927) to encompass the understanding and experience of Being itself, and developed his original theory of a non-dualistic person. According to Heidegger, philosophy is not a scientific discipline at all, but more fundamental than science itself (which for him is one way of knowing a world that does not have specialized access to truth).

Heidegger accepted phenomenology as a metaphysical ontology, and not as a fundamental discipline, which Husserl considered it to be. Heidegger's development of existential phenomenology had a great influence on the subsequent movement of French existentialism.

In addition to Husserl and Heidegger, the most famous of the classical phenomenologists were Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merlot-Ponti (1908-1961), Max Scheler (1874-1928), Edith Stein (1891-1942), Dietrich von Hildebrand (1889-1977), Alfred Schutz (1899-1959), Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) and Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995).

Phenomenological reduction

Gaining ordinary experience, a person takes for granted that the world around him exists independently of himself and his consciousness, thus sharing the implicit belief in the independent existence of the world. This belief is the foundation of everyday experience. Husserl refers to this positioning of the world and the entities within it, defining them as things that transcend human experience. Thus, reduction is what opens up the main subject of phenomenology - the world as a given and given of the world; both are objects and acts of consciousness. It is believed that this discipline should act within the framework of the method of phenomenological reduction.

Eidetic reduction

The results of phenomenology are not intended to collect concrete facts about consciousness, but rather, they are facts about the essence of the nature of phenomena and their abilities. However, this limits the phenomenological results to facts about the experience of individuals, excluding the possibility of phenomenologically substantiated general facts about experience as such.

In response to this, Husserl concluded that the phenomenologist must make a second reduction, called eidetic (because it is associated with some bright, imaginary intuition). The goal of eidetic reduction, according to Husserl, is a set of any considerations regarding contingent and randomness and concentration (intuition) of essential natures or essences of objects and acts of consciousness. This intuition of entities proceeds from what Husserl calls "free variations in the imagination."

In short, eidetic intuition is an a priori method of gaining knowledge of needs. However, the result of eidetic reduction is not only that a person comes to the knowledge of essences, but also to an intuitive knowledge of essences. Entities show us categorical or eidetic intuition. It can be argued that the Husserl methods here are not so different from the standard methods of conceptual analysis: imaginary thought experiments.

Heidegger Method

For Husserl, reduction is a method of leading phenomenological vision from the natural relationship of a person whose life is involved in the world of things and people back into the transcendental life of consciousness. Heidegger considers phenomenological reduction as the leading phenomenological vision from the awareness of a creature to an understanding of the being of this creature.

Some philosophers believe that Heidegger’s position is incompatible with Husserl’s theory of phenomenological reduction. For, according to Husserl, reduction should be applied to the "common position" of the natural attitude, that is, to faith. But, according to Heidegger and the phenomenologists he influenced (including Sartre and Merlot-Ponti), our most fundamental attitude to the world is not cognitive, but practical.

Criticism

Many analytical philosophers, including Daniel Dennett (1942), have criticized phenomenology. On the grounds that her explicit first-person approach is incompatible with the scientific approach from a third-person perspective. Although phenomenologists object that natural science can only make sense as a human activity that involves the fundamental structures of a first-person perspective.

John Searle criticized what he calls a “phenomenological illusion,” believing that that which is not phenomenologically present is not real, and that which is phenomenologically present is actually an adequate description of how everything really is.